In the spring of 1932, at Nanzen-ji, in Kyoto, Japan, an American woman sitting in meditation had an awakening. After wrestling with a koan, Ruth Fuller Everett, a wealthy 40-year-old wife and mother from Chicago, received a glimpse of a new reality. When she conveyed this to her Zen master, Nanshinken Roshi, he invited her to enter the zendo [meditation hall] and sit with the male monks. This was an unprecedented event. Ruth became the first American documented to have experienced satori, or sudden enlightenment.

She went on to achieve other historic firsts: she was the first Western woman to ordain in the Zen tradition in Japan and the first to become abbot of a Japanese temple. (She was named the temple priest at Ryosen-an temple in Kyoto, in the 14th-century lineage of Daitoku-ji; this acknowledgment was so unusual for a Westerner and a woman that it warranted an article in Time magazine.) She made a valuable contribution to Western Buddhism in her translations of Japanese texts and wrote lucid explorations of Rinzai Zen and koan study. Seeing that Zen could offer liberation from suffering, she set out to find a way to bring this remedy to her own country amid the end of the Depression and the buildup to the Second World War. “She considered herself a scientist, a researcher who might discover a cure for the malaise she witnessed in the world all around her—or perhaps not discover something new so much as receive, translate, convey an ancient well-known solution back to her own land,” co-authors Janica Anderson and Steven Schwartz write in Zen Odyssey: The Story of Sokei-an, Ruth Fuller Sasaki, and the Birth of Zen in America.

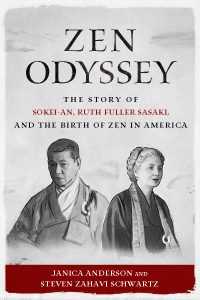

Zen Odyssey tells the full story of this pioneering woman, intertwined with that of the Japanese Zen master Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki, who was first her teacher, and then her husband, with whom she ran The First Zen Institute of America in New York City. The book traces the early lives of these two outsize personalities, chronicling their initial, contentious encounter and fruitful working relationship, which eventually led to a lasting connection. The authors draw upon the recordings gathered by the writer and poet Gary Snyder, who conducted 27 hours of interviews with Ruth in 1966, a year before her death. The interviews provide a window into her thoughts and feelings, as well as her understanding of Zen, particularly the zazen [sitting meditation] and koan practices of Rinzai. Photographs and the writings of Sokei-an add to the book’s rich tableau.

Zen Odyssey presents Sokei-an’s journey as parallel with Ruth’s. Sokei-an was born in 1882 in Japan to a Shinto priest who died when Sokei-an was 15 years old. Sokei-an took up Zen training, and in 1905 was brought to the United States by his teacher, Sokatsu Shaku. Sokatsu soon returned to Japan, and Sokei-an was left to fend for himself in America. He relied upon his considerable skills as a sculptor and wood-carver to earn a living; he also worked as a writer for a Japanese-language periodical. He was equally comfortable in the bohemian hangouts of Greenwich Village as he was in the backwoods and mountains of the Pacific Northwest, where he wandered on prodigious solitary hikes.

In trips back to Japan, during the next decade, Sokei-an completed his koan training and in 1926 was granted inka [the final seal of approval in the Rinzai school of Zen] and given the title of roshi, a title used for a venerated Zen Buddhist teacher. With this authorization he went back to New York City and began his labors as a Zen master to Americans. In 1931, he established the Buddhist Society of America, which was later retitled the First Zen Institute of America. He began giving talks there, and became the first Zen master to live in the U.S., lecturing, writing, and teaching in English.

In 1933, at the Buddhist Society of America, Ruth and Sokei-an met for the first time. They engaged in verbal dharma combat, Sokei-an stating that Americans were not ready for zazen and Ruth arguing that it was essential practice for them. Sokei-an countered that Americans have too many ideas, but when Sokei-an asked her whether he should adopt a sharp, direct approach to students or be patient and kind with them, she surprised him by replying, “Why not just be yourself?” and won Sokei-an’s respect. For her part, she found herself responding to his exceptional presence, “a fullness . . . a power somehow both raw and refined.”

Ruth began attending sessions at the Buddhist Society of America and working with Sokei-an, settling into the relationship that would guide their lives until Sokei-an’s death in 1945. She supported and promoted the Buddhist Society of America with the confidence born of privilege coupled with a brilliant mind. Because she had spent a year in Japan in a Zen temple, she had special knowledge and definite ideas about how things ought to be done. Things didn’t always go smoothly: some students resented her for her wealth and for Sokei-an’s particular interest in her. She purchased a five-story building in Manhattan to house the center, and, though still married to her ailing husband, grew closer to Sokei-an. Sokei-an was still married to his wife in Japan, but as he and Ruth worked together to translate Rinzai texts, their interest in each other developed. In January 1940, Ruth’s husband died, and she was now free to enter fully into her relationship with Sokei-an.

Meanwhile, the United States was making preparations for war after Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and began interning people of Japanese descent. Sokei-an was arrested on June 15, 1942, and taken to internment camps first on Ellis Island, and later Fort Meade in Maryland. The next year became a time of anxious effort: conditions in the camp were horrific, and Sokei-an, in his sixties, suffered from poor health. Ruth and others lobbied to get Sokei-an out of prison. She hired a lawyer who knew people in the government and could use his influence. She organized Sokei-an’s students and friends to brainstorm and write letters. One of the students, a commander in the navy, worked behind the scenes to secure Sokei-an’s release. Finally, on August 17, 1943, Sokei-an became a free man. Not long after, he experienced an acute coronary thrombosis and was incapacitated for a time.

Ruth and Sokei-an were in love, and they wanted to marry, encouraged as well by the doctors who urged marriage as a support for Sokei-an’s recovery. But first, Sokei-an had to obtain a divorce from his wife in Japan. A trusted lawyer told him that in the state of Arkansas, if he and Ruth established six-weeks’ residency and put public announcements in the newspapers, Sokei-an could get a divorce. The lawyer found a Christian minister in Little Rock to act as local sponsor.

Ruth and Sokei-an followed his advice, going to live for six weeks in Little Rock. However, their union was blocked by Arkansas’s anti-miscegenation laws, which prohibited the marriage of people from different races. A sympathetic judge eventually ruled in their favor, and they were married, but soon after, Sokei-an collapsed from high blood pressure. He suffered a kidney thrombosis a few days later, and he died on May 17, 1945.

His death came as a terrible shock to Ruth and the First Zen Institute community. Ruth Fuller Sasaki and Sokei-an Sasaki had planned to go on studying, building, and teaching together for decades to come. Instead, she found herself in a new chapter of her life, continuing the work of the First Zen Institute alone, and searching for an appropriate successor to Sokei-an.

The last third of the book chronicles this search and describes her efforts and successes in war-ravaged Japan. There, she did her best to rebuild the temples she loved, was given full ordination and the title of roshi, and named temple priest. She brought together a team of Asian and Western scholars to translate texts in the Rinzai Zen tradition and worked with them to produce several volumes. These decades involved frequent trips to Japan and back to New York, and many challenges, both in her relationship with her presiding Zen master and with the sometimes-fractious members of her translation team. In Japan she often lived in austere conditions, particularly inadequate heating in the winter, which took its toll on her health as she entered her seventies. In the U.S. she put forward Sokei-an’s teachings, and was not disconcerted that the Soto Zen of Shunryu Suzuki was becoming more attractive to Americans than the narrow path of Rinzai. Rinzai Zen is not for everyone, she asserted—the numbers of students did not matter, only the purity of the transmission that had been given to her through Sokei-an and others. She died in Japan just a week before her 75th birthday in 1967, and was cremated and buried with much ceremony.

I encountered Ruth Fuller Sasaki’s work in the early eighties, at the beginning of my Buddhist practice, seeking her out because she was one of the few female authors addressing Buddhist issues, but also because I was curious about Rinzai practice. I read The Zen Koan: Its History and Use in Rinzai Zen, which Ruth co-wrote with Zen teacher Isshu Miura, and came away from it impressed with her capacities and curious about the life story of an American woman so versed in Zen. Finding her again in the pages of Zen Odyssey was a pleasure.

The stories of Ruth and Sokei-an reveal two characters of titanic proportions—original, colorful, demanding; the material gleaned from the interviews by Snyder in particular takes us deep into the passionate lives of these pioneers. At times, the authors provide more than we need to know—for example, in the many pages devoted to Alan Watts’ courting and marriage to Ruth’s daughter—and at moments we would like to read more about the intimate relationship that developed between Ruth and Sokei-an. After Sokei-an’s death the account can bog down a bit in the Japanese Zen politics dogging Ruth. But, these quibbles aside, Zen Odyssey offers a rich personal history of the bringing of Buddhism to America—which Sokei-an said was as difficult as planting a lotus on a rock—and the fascinating characters who managed it.

Zen Odyssey: The Story of Sokei-an, Ruth Fuller Sasaki, and the Birth of Zen in America by Janica Anderson and Steven Zahavi Schwartz, is published by Wisdom Publications.