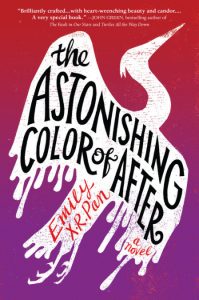

In Emily X. R. Pan’s debut novel, The Astonishing Color of After— a New York Times best-seller—readers are instantly captivated by Leigh Chen Sanders, Pan’s artistic and thoughtful teenage heroine. But as Leigh navigates typical high school struggles, she also watches her mother struggle with severe, treatment-resistant depression, eventually losing her to suicide.

Like her character Leigh, Pan is a visual artist, and a love of color and beauty is evident throughout her novel. Born in Illinois to Taiwanese immigrant parents, Pan says she grew up with a strong sense of her family’s history, including the Buddhist traditions her parents worked to pass down.

Below, Pan discusses the moment she realized just how much Buddhism influenced her book and how she felt writing about her cultural identity.

Congratulations on such a moving debut! A large part of The Astonishing Color of After takes place in Taiwan because Leigh travels there after her mother’s death to meet her extended family for the first time. How did you prepare to write those scenes?

I visited Taiwan a handful of times when I was growing up. The book originally took place in Shanghai because there was weird family drama that made my mom say that she didn’t want me to visit Taiwan. But while I was revising I said, “This doesn’t make many sense [to have the story in Shanghai]; this needs to be in Taiwan.”

So I ended up scheduling a trip to Taiwan in 2016, and it was the first time I went there as an adult. I wanted to walk the streets in my character’s shoes. Before that, I barely remembered Taiwan myself. I remembered what my family looked like, sort of, but not the streets. My sense of direction was off.

Leigh visits several Buddhist temples during her time in Taiwan, and a major part of the book centers on Leigh’s belief that her mother, Dory, was transformed into a bird immediately after she died. Despite both of those things, I was struck by a tweet you wrote recently in which you said you did not realize until well into the revision process how heavily Buddhism influenced your story.

There were a lot of things in the book that I definitely made more Buddhist over time. When I sold the book, it looked very different. Originally the story was hopping in and out of a fantasy world, but I completely stripped that out later.

Then when my agent asked me if there were cultural or spiritual influences in the book, I said, “No, not really.” But then later I thought, “Oh, wait!” I was raised Buddhist, and my mom would constantly talk about this life and previous lives and the concept of karmic debt. These beliefs and philosophies were deeply ingrained in me.

I didn’t originally WANT to write Buddhism into my stories. I had spent time thinking about it before. I’d worried that it wouldn’t be accessible to readers.

In other words, I was erasing my own culture for what I believed to be “marketability.” How sad is that?

— Emily X.R. Pan (@exrpan) March 14, 2018

But you also tweeted that you almost took those Buddhist allusions out because you were worried about how they’d be received.

I thought it wouldn’t be palatable or that people would say, “Oh, it’s a religious book.” I really worried about the marketability of it. But people have found it really interesting. A lot of people actually think the bird is Leigh’s mother reincarnated, but it’s not.

Can you explain that a little more for readers who are unfamiliar with these concepts?

Sure. The idea of reincarnation is that you are returned to this world in the form of another living creature, depending on the actions taken in your life. So if, based on those actions, you need to learn something like servitude, you might return as a dog. If you’re lucky, you return as a human baby again. Or you might not be reincarnated at all, and instead journey toward hell, or toward the Western Paradise [or pure land, a celestial realm in Mahayana Buddhism], moving in the direction of nirvana.

Before any of that happens, there’s a period of limbo that can last up to 49 days, during which time the transition is being determined. I lost my aunt to suicide; my family was praying every day during that 49 days, and they were also paying monks in Taiwan to pray for her during those days so that her soul could journey on towards the best outcome. There’s this idea that you shouldn’t cry too loudly during those days because your loved one might hear you, and that might distract or hinder them as they try to move on.

Did you grow up going to Buddhist temples during your childhood in Illinois?

We didn’t really go to temples in the States, but we would when we went back to Taiwan. When my grandfather died, we did all of these rituals for him, and his ashes are stored in a temple there. And my mom would keep an altar in the house and do offerings.

I often explain it to people by saying we are Buddhist the way people who only go to church for Easter mass and Christmas are Christians. Just because you don’t go to temple regularly does not mean that these ideas are not part of you or your everyday life.

I actually keep an altar in my apartment now, and just looking at it brings me comfort. We also have Buddhist chants playing at low volume all of the time; you can always hear them in my home. So these Buddhist ideals that I was raised with have stayed with me.