The landscape of North American Buddhism was, in its broad outlines, first shaped most significantly by Japanese Buddhism. While the contours of that landscape have been filled in over the years by Buddhist traditions originating throughout Asia, the roots of Buddhism in North America continue to be strongly intertwined—in ways readily apparent and in ways hard to see—with Japan’s religious culture. Especially elusive is the influence of esoteric Buddhism.

For most North American Buddhists, the tantric teachings and practices that developed in India are known by way of the forms they took in Central Asia, especially Tibet. But Buddhist tantra also took root in East Asia, where its transmission followed a very different path (and where it was historically referred to most often as a body of “secret,” or esoteric, teachings.) While today schools of Japanese Buddhism such as Shingon and Tendai represent the dominant esoteric traditions, for centuries esoteric Buddhist teachings and practices were incorporated into the framework of many schools. In ways both diffuse and specific, esoteric Buddhism has had a great influence throughout the history of Japanese Buddhist traditions, including such schools as Zen, Shin, and Nichirenshu, which are more familiar to most contemporary Buddhists than Shingon but developed several centuries later.

The following article is the second in a series of three essays on the esoteric Buddhism of Japan. [The first was “Becoming a Buddha” in the Winter 2017 issue.] This essay focuses on Kukai—also known by the honorific Kobo Daishi—who is often credited with introducing esoteric Buddhism to Japan (though this is not exactly true) and with founding the Shingon school (which is also not precisely the case). As Aaron P. Proffitt’s essay shows, Kukai was a person remarkable both for his spiritual accomplishment and his religious and temporal abilities. He was and remains a towering figure in Japanese Buddhism’s development. Japanese esoteric Buddhism, and Kukai himself, are little known in North American Buddhist circles. And that itself might be what most recommends them to our attention. When we look, we will find things familiar and things seemingly quite foreign. One can learn from both, but I think it is the latter that has most to offer. In grappling with difference, one’s own assumptions, usually so hard to see, come into focus, and in that way one’s horizons grow wider and richer.

—Andrew Cooper, Features Editor

In all of Japanese history, seldom has an individual’s legacy captured the country’s imagination as has that of Kukai, the legendary founder of the Shingon school of Buddhism. Kukai (774–835 CE), posthumously named Kobo Daishi (“the great teacher who spread the dharma”), is widely regarded not only as the founder of one of the most influential schools of Japanese Buddhism, but also as a bodhisattva-like savior figure still active in the world, leading beings to awakening.

shingon

Literally, “true word,” or mantra, the Shingon school is one branch of East Asian esoteric Buddhism.

Although he is little known among Buddhists in Western countries, local legends about Kukai and the miracles he is said to have performed may be found in towns and villages throughout Japan. Two sites in particular have been made famous by his legacy. One is Mount Koya, the monastic complex that houses his mausoleum, revered by some even today as an earthly Pure Land, a paradise from which one can readily attain complete enlightenment. The other is not a single site but rather comprises 88 temples along a pilgrimage route around the island of Shikoku, a route that purportedly retraces the path Kukai took during his time as a wandering ascetic. As Kukai the monk was reimagined as Kukai the saint, Kukai the savior, and Kukai the founder, he emerged as a major force in the history of Japanese religion. But there is a space between the Kukai of history and the Kukai of faith, between Kukai the monk and Kobo Daishi the saint. By taking up both perspectives, we can gain a fuller and richer understanding of the life and legacy of this towering figure.

***

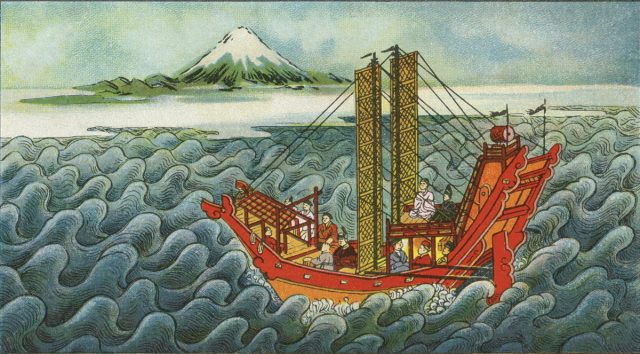

Kukai was born to a middling aristocratic family on the island of Shikoku. He began his education in the national academy, training in the Confucian classics, as most East Asian males of his class were apt to do. For reasons unknown to us, he dropped out of school and set upon the wandering path of the ascetic. At some point during his travels, he had a profound mystical experience, a vision he could not understand or explain. Soon thereafter he learned of the Mahavairocana Sutra, a tantric Buddhist text that seemed to illuminate the meaning of his vision. But he was frustrated by his teacher’s inability to explain the many mantras that were key to fully appreciating the text. His aspiration to find a teacher who could give him the instruction he sought led him to join, in 804, a mission to China to study in Chang’an, the capital of the Tang dynasty and the center of the East Asian Buddhist world.

Once in China, Kukai took up residence at Qinglong Temple. According to Kukai’s own account, the Buddhist master who served as the head priest there, Huiguo (746–805), rejoiced at his arrival, sensing that someone worthy of his teachings had finally arrived. Under Huiguo’s instruction Kukai studied what many regarded as the pinnacle of Buddhist wisdom: the esoteric, or “secret,” teachings of the Buddha.

The practices and teachings found in tantric lineages are generally deemed “esoteric” for two related reasons: First, many aspects are kept hidden from noninitiates, and in fact many ritual manuals are written with gaps that require the oral commentary of one’s teacher. Second, the Buddha is said to have taught different things to different people in accord with their capacity to understand and progress on the path. Sometimes the Buddha’s true meaning was not readily apparent on the surface, the “exoteric” level. Tantric traditions hold that some teachings either were secretly transmitted to a group of advanced students or required additional elaboration to reveal the “esoteric,” hidden meaning that would allow one to make rapid progress along the bodhisattva path, even to the attain attainment of Buddhahood in this very body in this very life. In addition, esoteric practices were said to empower one to perform rainmaking rituals, and gain health, wealth, longevity, and other worldly benefits.

***

Because the early study of Buddhism in Europe and North America took place under significant influence from Protestant Christian culture, a pervasive skepticism toward ritual as a significant expression of authentic spiritual life has led many Buddhist “modernists” to downplay such things as ritual, image worship, and devotion as major features of Buddhist practice, preferring instead an emphasis on highly secularized views of meditation and doctrine. For Kukai, as for other Buddhist tantric practitioners of both East Asian esoteric Buddhism and Indo-Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, tantric practice was considered the most rapid path to the attainment of full, complete awakening. Through initiation into esoteric tantric lineages and the coordinated ritual practice of mudra, mantra, and mandalic visualization—that is, rituals of body, speech, and mind—it was said one could attain union with the body, speech, and mind of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. While the practitioner initially feels these forms to be in some sense directed outward, continued practice reveals the veil separating buddhas and ordinary beings to be immaterial; ordinary beings as well as buddhas participate in the ultimate reality. This approach, though represented to greater or lesser degrees across a broad spectrum of Mahayana tradition, was a central feature of Kukai’s teaching.

In China, Kukai was initiated into the use of two esoteric mandalas, the Taizokai mandara (Womb Realm Mandala) and the Kongokai mandara (Vajra Realm Mandala), and studied the Mahavairocana Sutra and the Vajrasekhara cycle of tantric texts, which correspond respectively to the two mandalas. The Womb Realm Mandala is said to represent the universe as it is in its true state, while the Vajra Realm Mandala represents the wisdom necessary to grasp the true nature of this reality. These mandalas, depicting two interrelated views of reality, are potent objects of meditative visualization and devotion. It is often said that the Mahavairocana provides much of the doctrinal content that informed Kukai’s approach to Buddhism while the Vajrasekhara provided the ritual dimension.

After almost two years, Kukai returned to Japan. He introduced a vast corpus of tantric ritual manuals that were for the most part previously unknown in Japan and transmitted an approach to Buddhism in which ritual and doctrine, practice and theory, were inextricably linked.

Kukai’s theory of Buddhist practice focused on the coordination of the three mysteries of body, speech, and mind, in which the body, speech, and mind of sentient beings do not function in isolation from the body, speech, and mind of buddhas. It was a holistic and corporeal approach to awaken ing, wherein one realizes that ordinary foolish beings and awakened buddhas are ultimately not two but one. Accordingly, Kukai asserted that Buddhahood could be achieved in this body, right here and now.

In time, Kukai garnered the attention of the emperor, who eventually allowed him to establish a chapel within the palace for the performance of esoteric rituals. In his treatises and commentaries, as well as his charismatic ritual performances, Kukai impressed both the ecclesiastical establishment and the emperor himself. This eventually led to the proliferation of esoteric Buddhist training lineages within the major temples of Japan. Through this close relationship with the emperor and the imperial family, Kukai was given permission to train monks at Toji, a temple built by the emperor in Kyoto, and he eventually took a leading role in the government’s central monastic bureau in the old capital in Nara. Kukai then began initiating and training monks who belonged to a variety of monastic institutions. At this time, becoming a practitioner within these ritual lineages did not require that one convert from one kind of Buddhism to another. If you were, say, a scholar of the Lotus Sutra or Yogacara philosophy or a devotee of the Buddha Amitabha, adding esoteric ritual to the mix was simply a matter of receiving initiation and training under a qualified master. With Kukai overseeing the central monastic administrative office, this is precisely what happened at many of the major monastic institutions in Japan. Kukai’s diplomatic approach to introducing esoteric thought and practice has inspired Buddhist practitioners up to the present.

Kukai asserted that Buddhahood could be achieved in this body, right here and now.

Mastery of esoteric Buddhism required long periods of dedicated practice and meditation under the tutelage of accomplished masters, and Kukai wanted a retreat center for training monks far away from the hustle and bustle of the capital. In 816, he was granted the site of Mount Koya, where he established a monastic training complex. Kukai was an accomplished meditator, renowned calligrapher, skilled monastic administrator, sought-after civil engineer, and powerful ritual master. His status as a renaissance man, however, placed great demands on him, which eventually took their toll. He died at Mount Koya, without seeing the full completion of the monastic complex.

One common misconception about Kukai is that he introduced to Japan a new school of Buddhism, against which all other forms of Buddhism were to be found lacking. This misunderstanding is likely the result of an overly literal and decontextualized reading of certain works attributed to him. Kukai asserted that the esoteric truth of the Buddha’s awakening is found to a greater or lesser extent in all paths, Buddhist or otherwise. That truth of the Buddha’s teaching was simply more explicit in esoteric texts than in exoteric texts, as the latter cloaked this deeper truth in upaya, or skillful means, for the benefit of those not ready for the directness of the esoteric teachings. The new ritual texts and theories that Kukai introduced were to be used as tools for looking more deeply and more actively into the forms of Buddhism already in existence.

Kukai did not regard himself as the founder of a new school or sect, and he appointed no successor. He trained monks from a variety of backgrounds and helped to establish esoteric Buddhism as a major area of study to be practiced alongside other ritual and doctrinal traditions. Following his death, training in esoteric Buddhism became an essential component of the curriculum used to train monks at the major temple complexes throughout Japan. Moreover, subsequent generations of monks from across Japan embarked on their own voyages to China to receive new esoteric initiations, texts, and ritual artifacts.

***

By the 10th century, the Tendai school, centered on Mount Hiei, came to dominate Japanese Buddhist culture in both doctrine and ritual practice. With its incorporation of esoteric ritual, Pure Land devotion, and Lotus Sutra teachings—not to mention skillful political maneuvering—it remained so until the late 16th century. Japanese Tendai is derived from the Chinese Tiantai tradition and was transmitted to Japan by Saicho (767–822), who traveled to China as part of the same envoy as Kukai. Saicho had returned before Kukai and was thus the first in Japan to teach esoteric Buddhism. Saicho had studied esoteric teachings during his training in the Tiantai mountains in Eastern China; Kukai, by contrast, had studied in the cosmopolitan capital, Chang’an. Because of his superior erudition in Mahayana esoterica and his diplomatic skill, Kukai quickly surpassed Saicho as Japan’s leading Buddhist teacher of the time. But because Kukai did not appoint a successor or found a distinct school, his place in Japanese Buddhism soon diminished. The study of his treatises fell out of fashion, and Mount Koya—faced with financial hardship, fire, loss of status and political support—was virtually abandoned. Kukai the monk, and his mountain, were all but forgotten for nearly two centuries.

In the 11th century, however, monks in the capital in Kyoto again began reading Kukai’s texts. Furthermore, monastics in Nara and Kyoto started working to revitalize Mount Koya as a pilgrimage site and a monastic training center. While Tendai remained the dominant Buddhist school, from this time on, we see an evolving reinvention, recreation, and reimaging of Kukai.

Devoted recorders and commentators on Kukai’s life and teaching claimed that he did not die in the normal sense but rather entered into an eternal samadhi, or deep meditative absorption, and is awaiting the descent of the bodhisattva Maitreya, the next buddha for our world. Devotion to Maitreya and aspiration for rebirth in the Tushita heaven where he resides had long been popular among Buddhists across schools and traditions. Because of belief in Kukai’s close connection to Maitreya, Mount Koya itself came to be recast as a Pure Land in the midst of our world, a place where one’s practice, whatever its focus, would be rendered more effective.

Today, when one hears of Buddhist Pure Lands, one is likely to think of devotion to the Buddha Amitabha, or to schools centered on attaining rebirth in the Pure Land in which he abides, and to the practice of nenbutsu, of calling his name (“Namu Amida Butsu” in Japanese), since this is the dominant form of Pure Land aspiration in East Asia as well as in Western countries. It is, however, basic to traditional Buddhist thought that all buddhas and bodhisattvas “purify” their spheres of influence, and so devotion to the Buddha Amitabha is but one form of Pure Land practice relating to Mahayana sutras and tantras. A Buddhist may aspire to be reborn in the abode of a bodhisattva such as Maitreya or Avalokiteshvara (the Bodhisattva of Compassion) or in that of a buddha such as Akshobhya (who resides in a Pure Land to the East of our world).

On Mount Koya, a unique esoteric Pure Land culture developed. Following the 11th-century revival of Kukai studies and the establishment of Mount Kōya as a popular pilgrimage site, Kukai came to be regarded as a bodhisattvalike figure and a kind of savior. Aristocrats, samurai, members of the monastic elite, poets, wandering ascetics, and others from various walks of life traveled to Mount Koya seeking Pure Land rebirth and the purification of their karma. In addition to chanting the nenbutsu, practitioners were encouraged to chant the “treasure name of the great teacher” (daishi myogo), “Namu Daishi Henjo Kongo” (“Praise to the Great Teacher [Kukai], the Universally Illuminating Vajra”), as a kind of Kukai nenbutsu. Images depicting Amitabha’s descent from the Pure Land to usher back devotees, were worshipped along with the Womb and Vajra Mandalas, and even portraits of Kukai himself. Some features of this esoteric Pure Land culture remain active even to this day, as Kukai devotees (who are often, but not always, affiliated with the Shingon School) travel to Mount Koya to pray for their ancestors and for their own rebirth in the Pure Lands of the Mahayana universe. Here, Kukai is the saint who, from his own Pure Land on Mount Koya, ushers beings to various cosmic Pure Land abodes.

The 14th to 17th centuries saw the establishment of more clearly defined boundaries between different schools of Japanese Buddhism. Institutional hierarchies and discourses on the purity and continuity of sectarian institutions led to the creation of founder narratives and a more exclusive approach to Buddhist practice. But by the end of the 17th century, the samurai government in Edo (Tokyo) had passed a series of edicts clearly delineating the relationships between temples and institutions that required the exclusive study of the doctrines of sect founders. It was in this context that Kukai became the founder of the Shingon School. Before this time, the course of a monk’s career might include study of Zen meditation, Tendai scholasticism, Pure Land devotion, esoteric Buddhist ritual, and so on.

During the Warring States Period (1467–1603), rival warlords destroyed many temples, and in 1571 the power center of Tendai Buddhism, on Mount Hiei, was nearly wiped off the map. Yet Mount Koya managed to survive throughout the period, something that many regarded as miraculous. Filling the void left by the fall of Tendai, Shingon began to reshape itself as a more clearly defined school, and it was this later Shingon School that rewrote the history of esoteric Buddhism in Japan, with Kukai as the great founder and standard against which other esoteric traditions were to be judged. This way of thinking about the history of Japanese Buddhism, not surprisingly, tended to draw a clear line from Kukai the monk to the modern Shingon School.

Just as many modern historians of religion set out to find, say, the historical Jesus of Nazareth or Prince Siddhartha Gautama, modern scholars of Japanese Buddhism often focus their efforts on the historical founders of different Japanese Buddhist traditions. The historical Kukai now has a place in the copious amounts of meticulous scholarship aimed at uncovering what we can “really” know about the 8th-century monk whose legacy came to take on so many different forms. In the construction of the modern study of esoteric Buddhism, it was a new Kukai—Kukai the founder and philosopher—who moved to the foreground.

The academic study of religion and the “theological” study of religion (the study of religion by practitioners, for practitioners) are often assumed to be at odds with one another. When devotees or practitioners recount their own school’s history, the meaning of a text or tradition is often reinterpreted and applied to a new context. Practitioners interpret the meaning of an event or scriptural passage for the edification of devotees. The academic scholar of religion is not necessarily in the business of proving or disproving myth or legend, but rather aims to situate claims in particular historical, cultural, or political contexts—which in some cases may amount to the same thing. In other words, while these two ways of approaching Buddhism are different, they need not be the antagonists they are so often assumed to be.

In the space between these two modes of knowing, there can be in their difference not just conflict but also complementarity. In this space, religious figures can be seen anew, both as players in history and as carriers and embodiments of how different communities have found meaning in the buddhadharma. In such a space, with each perspective acting upon the other, we can better see Kukai the monk and Kobo Daishi the saint, side by side.