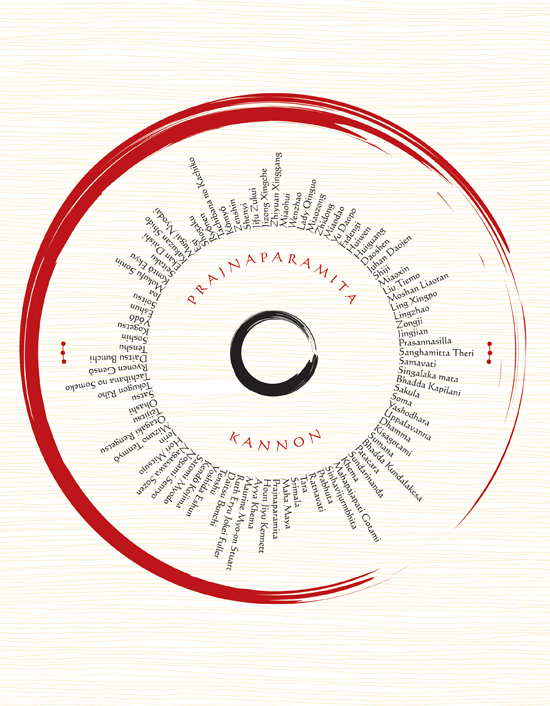

Rowan Percy keeps her Zen women ancestor document on her altar, wrapped in a scarf her mother used to wear. She unfolds the delicate sheet of rice paper. The names are splayed in a circle, counterclockwise, and expand like rays around the enso. Prajnaparamita, the mother of all buddhas, and Kannon, the bodhisattva of mercy and compassion, are scrolled in red in the center. The names begin here, in the mythical realm. Then the circle travels forward through 2,600 years of Buddhist history. The Zen tradition didn’t form until 6th-century China, but this document includes pre-Zen women ancestors important to the tradition’s heritage. As the centuries unfold, we enter the lives of women who practiced, taught, and awakened in India, China, Japan, and last, North America.

Percy received this document at her jukai—the ceremony in which one formally becomes a Zen Buddhist. It took place in 2007 at the Salt Spring Zen Circle, her small rural sangha that is tucked away on Salt Spring Island, one of the idyllic Gulf Islands that dot the southwestern coast of Canada. This document honors the women in Zen Buddhist history and lore. It is considered to be the first of its kind, though no one knows for sure. Others may have been lost or destroyed in one of the upheavals that affected the documentation of women’s history.

Related: Zen Basics

The transmission of Zen has, until now, been documented through a male lineage chart. Names on that traditional lineage include pre-Zen history too, forming a chain of ancestors that links the present-day teacher to the Buddha, stretching back about 90 generations. But now, instead of one, there are two charts: the traditional male lineage and the newly created women ancestor document. This document redresses history, honoring women’s names for the first time, and the documents are handed out together now in most jukai ceremonies in Soto Zen temples across the West.

The women ancestor document formed out of an urgent plea for change and a sense of injustice at the absence of women figures in Soto Zen history as it was being taught in the West. Its creation is an example of how history is adjusted for greater accuracy in light of a value system that honors women’s contributions. This document embodies a new story for Zen, a story that includes women. It also embodies a story of how history changes.

Since the first days of Buddhism, women have struggled to be included as full members of the religious community. The most famous example is the story of Mahapajapati, whose name appears in the eighth place on the document. She was the Buddha’s aunt and stepmother, who had raised him from just seven days old after his mother, Maya, had died. In the early days after the Buddha’s awakening, before there was a women’s monastic order, Mahapajapati made a radical choice. She dressed in a saffron robe, cut off her hair, and asked the Buddha to let women enter his order. He refused. Determined, she followed him barefoot to the city of Vesali, leading, it is said, 500 women. These women, writes Susan Murcott in The First Buddhist Women, wanted to “leave home,” just as male monastics did. Many hoped to “resolve ultimate questions of birth, suffering, and death,” and they wanted the Buddha as their teacher. The Buddha refused to admit women again, then a third time. Finally, the Buddha’s attendant Ananda stepped in. After Ananda pressed him, the Buddha finally conceded that women have full spiritual capacity. Even so, writes Murcott, for women to renounce home life was almost unthinkable; it called into question the deepest notions of gender roles and thus threatened to overturn society. Such a situation, the Buddha said, would hasten the decline of his teachings by 500 years. Nevertheless, acknowledging Ananda’s reasoning, he relented. From that day, women became full inheritors of his teachings, with an irreversible right to practice within the tradition.

Related: Making the Sangha Whole Again

But all of Zen’s women ancestors’ lives unfolded inside a chiefly male historical narrative, and Mahapajapati’s life was no exception. No matter how important a woman’s contribution to Buddhism was, her name would not make it into the traditional lineage chart. In this patriline, as in any patriline, there is no place for women. Quickly, women’s names and stories fade into the background or disappear completely, sometimes within the span of a single generation.

Lineage sits at the core of Zen, as the axis around which the tradition constellates. In Zen temples everywhere the male lineage is chanted every day, and the chart recording it is the central ceremonial document given to every ordained student. The lineage seeks to document how Buddha’s teachings—the dharma—were passed from person to person through the centuries. Transmission in Zen is described as “mind-to-mind,” something conferred intimately in the personal relationship between a living teacher and student. The spiritual ideal of Zen transmission is that a deep and wordless understanding passes between teacher and student, that in effect their minds become one, and because this lineage is said to extend back, unbroken, to the Buddha himself, each successor is heir to the Buddha’s awakened mind.

Twentieth-century scholarship shows that the unbroken chain of the lineage is partially fictional, a constructed history. Documenting a lineage didn’t even begin until about the 8th century in China, where it was adopted from the Confucian belief in ancestor veneration. According to the earliest scriptural sources, the Buddha himself did not name a single successor but instead entrusted his teaching to the monastic community. So from the time of early Indian Buddhism, beginning around the 6th century BCE to the emergence of Zen in the 6th century CE, a “lineage” by necessity had to be pieced together even if many of the Indian men’s names on it were historical figures.

As a social institution, Zen transmission had a number of practical functions. The lineage was a way to assign authority within Zen, establishing in no uncertain terms “the authenticity of teaching and practice,” as Buddhist scholar Miriam Levering writes, and was a way of “authorizing the current teacher.” In any religious tradition, spiritual authority often links with political and economic power, and this is also true in Zen. “Dharma transmission was always to some degree political,” Levering writes, as it “was required for a person to become the abbot or abbess of a Chan or Zen monastery.” Equally important, lineage transmission has historically been seen by practitioners as having an esoteric quality. It’s “a theological idea, an article of faith that grounds practice in an important way.” Students are reminded, in the words of Chinese Master Wumen Huikai, “In true Zen practice our very eyebrows are tangled with those of our ancestral teachers, and we see with their eyes and hear with their ears.” Indeed, “lineage paper” translates into Japanese as nothing less than “blood vein.”

Related: My Short Brilliant Zen Career

The stories of the men in the lineage are the defining narratives of Zen. Biographies found in sermons, poetry, and koans are of masters who exemplified Zen values like discipline, heroism, and iron will, and they point to how Buddha’s wisdom came alive in human lives. At their best, religious stories build a bridge linking a student’s inner religious life to a tradition and that tradition in turn to something of transcendent concern. Zen students the world over study these stories in just this way.

But for all their wonder and profundity, the male ancestor stories are told from the patriarchal worldview in which Buddhist history has so consistently been nurtured and recorded. And so women barely exist in the official history that was left behind. In Zen’s classical literature, written by men and,we can assume, with male audiences in mind, when women appear they are peripheral at best, abhorred at worst. Women are depicted as objects of desire, as distractions, and as temptresses to be avoided. Or they are elevated to otherworldy status. There are, however, occasions when women characters turn those stereotypes on their head. In these tongue-in-cheek stories, women get the better of monks in dharma combat and thus provide a great shock to the male ego. But as the Zen priest and teacher Grace Schireson writes in Zen Women, “We learn nothing about how they live as women.” Rather, we learn “how they serve to transform Zen monks, and how they serve to highlight great Zen masters.”

In postwar Europe, the French existentialist and feminist Simone de Beauvoir got to the heart of the very quandary faced by contemporary Zen women. We can’t talk about the history of art, literature, or philosophy—all defining narratives—without entering into an overwhelmingly male story. Woman is the “Other,” wrote de Beauvoir in her foundational feminist book, The Second Sex (1949). “She is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is the incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute—she is the Other.”

And yet, as de Beauvoir insists, “all existents remain subjects, try as they will to deny themselves.” A dissonance arises when a person’s experience of herself as a subject, a “free and autonomous being like all human creatures,” is absent in the narratives that define a tradition. The reality of women’s lives—their very personhood—and the existence of an inner world—the experience of subjectivity—are denied to women in the stories where they appear only as Other, where man is the norm and what is natural, and woman is neither. One consequence of this is a sense of alienation, of being on the outside looking in, of not belonging in some essential way. That dissonance is painful, always, but especially so in the moments when it first becomes conscious. For centuries, women’s invisibility has not only been accepted, it has gone unnoticed, even by women.

“Otherness” isn’t just a gender dynamic, of course. It can exist between any two groups when one holds enough power and privilege to define itself as subject and another as object. The “Other” then gets defined, categorized, stereotyped, made invisible, and sometimes even dehumanized. Otherness is precisely the thing that turns human lives into ghosts—the unnamed, unseen, and unheard—who haunt the space between the lines in our history books, the silent pauses of oral traditions and even the stories we tell around the dinner table.

In a monastic tradition, as Zen was for most of its history, genders are strictly segregated. The male community always held a position of overwhelming advantage: men had economic advantage because their monasteries were more generously funded than the women’s; they had religious authority and prestige supported by the centuries-old institution of patrilineal descent; and, of course, men benefited from the privileges of social and cultural beliefs and practices.

At the same time, practicing Buddhist women faced numerous obstacles: lack of economic support, unfair taxation and other government policies, fewer training temples, and being prohibited from entering the temples where men practiced. There were also prohibitions against women ordaining without a male guardian’s permission. In addition, women often had to contend with the widespread belief that female birth was itself a spiritual hindrance, that they could not become highly accomplished, and that their best course, as Buddhists, was to gain the merit to be reborn as a man.

This context created fertile conditions for women to become the “Other.” A dissonance thus emerged between how women got represented in official history and the actual reality of women’s history. The result is an incomplete picture at best or a false representation at worst.

Historical records show that women have always practiced Zen, albeit in fewer numbers than men. Some women were dharma heirs to the great masters. They taught, had dharma heirs of their own, and were abbesses of convents. In some accounts women even had male students, radically transcending the cultural norms for their time. In a few instances, women rose to fame.

The women who spent their lives in Zen practice, we must assume, had stories of historical and spiritual value, stories worth remembering and studying. These women must have influenced their students and contemporaries in important ways. But the lives and stories of these awakened women have always been downplayed.

For one angle on why this is so, we can go back to the beginning. Although the Buddha acknowledged women’s full spiritual capacity, he allowed them to enter the order only with conditions attached. There would be eight special rules, he said, unique to the nun’s order. The Buddhist scholar Rita Gross writes that among these rules was one saying that “any nun, even of great seniority, must always honor, rise for, and bow to each and every monk, even if newly ordained.” Most important, nuns were strictly forbidden from criticizing a monk, though monks could criticize nuns.

Related: The Man-Made Obstacle

In her book Buddhism after Patriarchy (1992), Gross writes that while these rules “presented no inherent barrier to women’s spiritual development,”they enshrined nuns as inferior to monks. Given that teaching, by its nature, requires the authority to reprimand and criticize from time to time, these rules would have prevented exceptional women from naturally becoming leaders. As Gross observes, “In a tradition that thrives and survives on the transmission of knowledge and insight from generation to generation of teacher and student, any group that is structurally prohibited from becoming important teachers will be seriously demeaned and diminished. Furthermore, the tradition will be seriously impoverished by the lack of their voices and insights.”

In the case of Zen, scholars have identified a few times in history when a woman could have been the next lineage bearer in a line of eminent teachers, but their names were omitted. In fact, as Levering writes, “If the lineage expanded, only slightly, to include all the dharma heirs of the great masters, instead of just one official lineage holder, one would become aware of the presence of women.”

Zongchi, for example, who lived in China in the 6th century CE, was the student of Bodhidharma, Zen’s legendary founder. Records indicate that she was one of his four dharma heirs, fully equal to her male counterparts, but she is not named in the traditional lineage document.

Eihei Dogen, the 13th-century founder of Japanese Soto Zen, had a training quarter built for women in his temple Eiheiji and expressed radically egalitarian views of women in his teachings. But within a few centuries of Dogen’s death, Eiheiji became off limits to women and remained that way for hundreds of years.

Soto Zen’s second most important figure, Keizan Jokin (1268–1325), gave dharma transmission to a woman disciple named Ekyu, the first female dharma heir in the Soto school. Keizan’s own mother, Ekan, was a teacher in her own right and had founded two temples, which she led as abbess. She was a major influence on Keizan, not least in encouraging women’s study and practice of Buddhism. But these women ancestors, even as fully transmitted teachers, don’t appear in the traditional lineage document.

Buddhism is, of course, a tradition that strives to end suffering, but concern with the suffering that is caused by gender stereotypes, constrictive narratives, and discriminatory customs is relatively new, at least in its public discourse. How women’s lives have been marginalized from the Buddhist narrative is still being discovered, acknowledged, and remedied. And it is very early.

Given this background, it is clear that a women’s lineage document, just like the male lineage, is not merely a record of names. It weaves an important narrative that positions women, for the first time in Zen’s history, as full members of the Buddhist community and for the first time makes women’s stories integral to Zen’s narrative. It is, in its way, one more step in recognizing women as full participants in the human story.

In 2007, Rowan Percy knew that at her jukai she would receive a lineage document that only listed men’s names. In the months leading up to the ceremony, she felt increasingly unsettled. Percy had been practicing for five years and was ready to receive the traditional sixteen bodhisattva precepts. But, as she said, she was not ready “to continue that tradition of setting aside, making invisible, or actively violently tromping on what women have brought to life and spirituality for so many millennia.” She decided to approach her teacher, Peter Levitt.

Levitt felt as if he had just been roused from a dream. Percy had come in tears: “There are no women here!”

“You’re right,” Levitt responded, now a little unsettled himself. “I hadn’t thought about it.” Whenever Levitt had read stories in Zen literature, it didn’t matter who was teaching—a man, a woman, a tree, or a raindrop—all that mattered was the dharma. Zen Buddhism holds that, from the standpoint of the oneness of reality, gender, like everything else, is ultimately an empty category, something without inherent existence. The Heart Sutra, which is chanted daily in Zen temples the world over, reminds students that “form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” This kind of perspective was a crucial part of what drew people like Levitt and Percy to Zen in the first place. But now a puzzling problem was presented: if gender is empty, then how can people be discriminated against on the basis of it? Many came to see this as an ironic and unjust contradiction.

When Zen teachers from Asia came to the West during the mid-20th century, they established coed training centers. Zen students were now practicing a unique blend of centuries-old Asian monastic teachings in a North American lay context. As leadership passed from an Asian or Asian-trained founder to a second generation, women quickly rose to the highest levels of leadership as equals with their male contemporaries, which was virtually unprecedented.

The place of women in Zen’s social organization was quickly changing, so it was just a matter time before the place of women in Zen’s narrative would be questioned too. As if roused from a dream, practitioners began to wonder, “Where are the women?”

At first, few noncanonical texts—those most likely to include the names and stories of women—existed in English translation. This lack was compounded by what Gross calls a “preference for male heroes” and an “androcentric recordkeeping” that had been widespread in Western scholarship. This bias among modern scholars perpetuated and augmented the deeply ingrained male bias that history had long held in place.

To reconstruct history with a more accurate representation of women’s lives, scholars and writers must turn to sources outside the official religious canon. Women’s stories—sometimes just fragments—are found in journals female teachers kept, in poems or koans, or in the writings of male masters who mentioned female students. At the same time, nonreligious historical records provide context to the social and cultural conditions of women’s lives.

By the 1990s this work was well underway. In the late 1970s, members of the Diamond Sangha in Hawaii founded a magazine called Kahawai Journal of Women and Zen. This publication, writes Levering, for the first time “brought women’s voices to the fore in North American Zen communities.” In academia, manuscripts were retrieved and translations, primarily by women scholars in the West, became available. Landmark books on women in Zen were written. This work continues to the present day.

Some communities, building on this new information, began to incorporate a chant of women’s names into their temple services. Still, around the time of Percy’s jukai there was no official female counterpart to the traditional lineage.

And so she spoke to Levitt. Levitt considered the ways in which he and his students were impoverished by not knowing their female ancestors, and he said to Percy, “I get it. We have to make a women’s lineage paper.”

After gaining the support of Norman Fischer, the spiritual director of Everyday Zen, the umbrella sangha of the Salt Spring Zen Circle, Levitt set to work. Over a period of many months, hunkered down at home on Salt Spring Island, he researched and compiled a list of all the names of women in Zen history he could find. He approached women teachers for assistance, and he drew extensively from the work of scholars and writers, in particular Sallie Tisdale’s Women of the Way. Once he had a comprehensive list, he hired the graphic artist Barbara Cooper to design it, and not long after, an initial document was born.

At the jukai ceremony, in which Percy received the precepts, a women ancestor document was given to all of Levitt’ s students, male and female. “I folded them in exactly the same way and size as the male lineage papers, and bundled them together,” says Levitt. “Both the men and women who received it were crying. They felt like a part of themselves had been returned.”

Levitt’s list of names was sent to the Soto Zen Buddhist Association in the US, and a committee of Soto Zen practitioners from across North America formed, headed by Grace Schireson, who had, along with others, already been at work on the creation of her own women’s lineage document. Two years later, an official list of names was voted on, and a standardized document for use in ordination ceremonies was officially approved. In the center of this document are two faint dotted lines, the “place where the teacher’s and newly ordained names are written,” said Levitt, “embraced by the circle of women ancestors.”

“This is how the world will go forward,” Percy said. “With no one left out.”