THE BODHI TREE

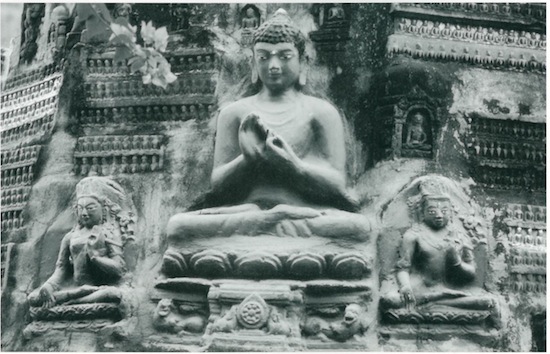

The spot under the fig, or Bodhi, tree where the Buddha attained nirvana is a kind of geographical omphalos or axis mundi for Buddhists. Buddhism was conceived under the Bodhi tree, the only spot on earth, the texts tell us, that was perfectly stable.

PETER MATTHIESSEN, 1978

In what is now known as Bodh Gaya—still a pastoral land of cattle savanna, shimmering water, rice paddies, palms, and red-clay hamlets without paved roads or wires—a Buddhist temple stands beside an ancient pipal, descended from that bodhi tree, or “Enlightenment Tree,” beneath which this man sat. Here in a warm dawn, ten days ago, with three Tibetan monks in maroon robes, I watched the rising of the Morning Star and came away no wiser than before. But later I wondered if the Tibetans were aware that the bodhi tree was murmuring with gusts of birds, while another large pipal, so close by that it touched the holy tree with many branches, was without life. I make no claim for this event: I simply declare what I saw there at Bodh Gaya.

From The Snow Leopard,© 1978 Peter Matthiessen. Reprinted with permission from Viking Press.

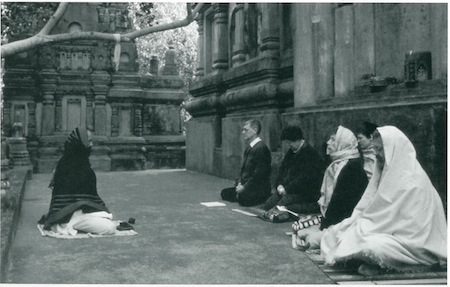

TENZIN GYATSO, THE l4TH DALAI LAMA, 1959

I reached Bodh Gaya. I was deeply moved to be at the very place where the Lord Buddha had attained Enlightenment . . . . Whilst there, I received a deputation of sixty or more Tibetan refugees who were also making a pilgrimage. A very moving moment followed when their leaders came to me and pledged their lives in the continuing struggle for a free Tibet. After that, for the first time in this life, I ordained a group of 162 young Tibetan novices as bhikshus. I felt greatly privileged to be able to do this at the Tibetan monastery which stands within sight of the Mahabodhi temple, next to the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha finally attained Enlightenment.

From Freedom In Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama. Reprinted with permission from HarperCollins Publishers.

ELIZABETH RUHAMAH SCIDMORE, 1903

Aside from the historic and religious associations of this particular bo- or pipul-tree, the Ficus religiosa has a character and interest quite its own, the effect of its symmetrical growth and well-balanced foliage masses, heightened by the continual agitation of its brilliant, dark-green leaves. Even on that still afternoon each individual, heartshaped leaf, with its long-drawn, tapering tendril tip, was trembling and spinning on its slender foot-stalk, until the whole tree mass was in agitation—every one of the myriad glossy, green leaves with a separate light as these thousands of perpetually moving mirrors caught the sun. The restlessness and activity of these bo-leaves, vibrating and striking together with a tinkling noise like the patter of soft raindrops on still nights, make the pipul the most grateful shade-tree, and the reflections of its glossy leaves suggest always the first stir of a rising breeze. This flashing, sparkling, flickering play of light all over the tree gives the pipul its unique and individual character—something like the dazzling, glittering trees that one sees in pictures by imperfect vita-scope. The pipul trembles to this day in reverence for the one who became Buddha beneath its branches, and as symbol of continual change and motion, the impermanency of the world. The pipul whispers to Rishaba, the Hindus say, every word it hears, for which reason it is never planted in the bazaar where trade must employ the lie. . .

Buddhists regard the Bo-tree as too sacred to be touched or robbed of a leaf, and devout Burmese pilgrims kneel, fix their eyes upon it, and in a trance of prayer wait until a miraculous leaf detaches itself and flutters down. It seemed sacrilege when the Brahman snapped off a leaf and offered it to me with the universal Indian gesture of the begging palm, and, at a request for more, snatched off a whole handful of trembling green hearts, as ruthlessly and brainlessly as the troop of monkeys in the bo-tree at Anuradhapura had done a few weeks before.

Despite the reverently worded mantra with which his own people address the tree, this Brahman butcher, responsive to a single rupee, continued to snatch off and break away twig after twig until l had a great green bouquet of nearly one hundred living, quivering leaves of Buddhist prayer. With no seeming appreciation of the sacrilege, he said: “Some people are satisfied with just one leaf. They bow to it, pray to it, and carry it away in a gold box.” Then he set himself down on the Vajrasana, the Diamond Throne, to yawn and scratch his lean arms as he adjusted his drapery.

From Winter India. Reprinted by permission of The Century Co.

ERIC LERNER, 1972-73

He pointed to a tree surrounded by a heavy, carved stone railing and a curious mixture of reverent pilgrims and gawking sightseers. We stood off to the side. I wondered if I was supposed to say anything. Nice tree. Big deal. Its bark was dry and blotchy, its limbs kind of droopy. Like an old, retired man whiling away his empty time on a park bench. I was ready to leave. Instead, we sat down on a flat stone surface in a comer of the courtyard. I noticed after a moment that Bill’s eyes were closed and his hands folded loosely in his lap. I did the same.

Almost immediately, that new-found sensor, which for lack of better understanding I referred to as my “body,” came alive. I felt a surge of power flowing through me.

My back straightened up and my head and shoulders pulled into line. I felt my chest drawn forward in the direction of that tree. An enormous calm enveloped me. All the noise and humming and activity receded to a faint background whisper. I intuitively felt some inkling, some tiny hint of what had transpired in this spot twenty-five centuries ago. Was still going on.

From Journey of Insight Meditation: A Personal Experience of the Buddha’s Way by Eric Lerner. © 1977 by Schocken Books, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Schocken Books.

“When I looked at the king of trees,

I knew that even now I was looking

at the Self-Existent Master.

If the tree of the Lord comes to die,

I too shall surely expire!“

From the Ashokavadana, 2nd-century C.E.