An eleventh-century Burmese king honored his conversion to Theravada Buddhism by building Pagan, an imposing city containing 13,000 temples and pagodas on the fertile plains of the Irrawaddy River. Slaves constructed this spectacular homage to the teachings of the Buddha.

In the late twentieth century, a Burmese dictator commands a military government that tortures, murders, and impoverishes its own people. The general, the soldiers, and the victims are all Buddhists.

For these many centuries, abuse and warfare have existed side by side with Buddhist teachings. What is the role of Buddhism in the tragedy of Burma? Is there any way the teachings of the Buddha can put an end to the cycles of violence? Burma’s past is not remarkably worse than that of other nations, but the centrality of Buddhism, with its emphasis on nonviolence and compassion, makes the situation in Burma difficult to comprehend.

As we sort through these questions, our Western perspective imposes biases and misunderstandings. We can see Asian Buddhism only from the vantage point of outsiders. Furthermore, we in the West surely cannot cast stones but must scrutinize the historical impact of Western religions with the same rigor we apply to Buddhism in Asia. Nonetheless, if we are concerned about the transmission of the dharma to societies in the twenty-first century, we might try to understand, albeit with humility, this paradox of a Buddhist nation in self-inflicted agony.

Burma sits between India and China. On its eastern flank, Burma shares a long jungle border with Thailand. Although it encompasses an area only the size of Texas, Burma has an elongated north-south reach, stretching from Tibet to the Indian Ocean. The peripheral border areas are mountainous and largely inaccessible, whereas the lowlands, with wide river valleys for rice cultivation, have a greater population and are the site of Burma’s cities. Both the neighboring border countries and the inhabitants of the peripheral regions play significant political, economic, and social roles in the Burmese drama.

Variety and complexity characterize the nation’s forty million people. The Burmans, for whom the country is named, are the dominant group; comprising approximately two-thirds of Burma’s population, they practice Buddhism and reside in the central lowlands. In the jungle and mountain peripheries of Burma, approximately seventy ethno-linguistic groups make their homes and attempt to maintain their traditional ways of life. Major groups include the Karen, Karenni, Shan, Mon, Kachin, and Arakan. Most of the ethnic groups practice slash-and-burn agriculture, forage in the forests, and trade natural resources for their modest economic needs. Many are Buddhists who trace their lineage directly back to the time of the Buddha; others converted to Christianity during the nineteenth century. Small groupings in western Burma are Muslim. Historically, the ethnic minorities have not identified themselves primarily with Burma as a nation. Some speak nothing except their own languages and reside astride both sides of arbitrary national borders established in the jungle. Over the centuries any attempt to solidify a nation out of such diversity failed.

Burma has also been well endowed with natural resources. In addition to the world’s largest remaining teak forests, natural resources include tin and tungsten, jade, gold and rubies, oil, fish, a thriving opium trade and enough paddy to have once been called the “rice bowl of Asia.”

A Burmese legend claims that Buddhism has existed in Burma continuously since the visit of the historical Buddha 2,500 years ago. Three centuries after the Buddha’s death, the Indian emperor Ashoka entered the area that is now Burma to propagate the new faith, establish the sangha, and initiate the monastic order that continues unbroken to our own day. Burmans migrated to the region from eastern Tibet, settling in upper Burma and bringing Mahayana Buddhism with them. However, during the eleventh century (the Golden Age of Pagan), a Burman king was converted to Theravada Buddhism by a Mon monk practicing in the tradition of Sri Lanka. Thus did the Theravadan tradition take root and become the established practice and unifying communal and cultural identity of the Burman people.

Prior to the British colonial period during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, struggles for power and domination between the Burman majority and the ethnic groups or neighboring countries pervaded Burmese history. Although at present the Burman military clearly commands the government, at other times in history the Mon or Shan minority peoples ruled the country. The continual presence of Buddhism has not visibly affected state behavior.

The Burmese felt humiliated and disenfranchised in their own land during the British occupation. Many remembered King Mindon, dethroned by the British and paraded in an oxcart in front of his people en route to exile in India. Britain annexed Burma and administered it through India. The British and Indians displaced the Burmese in running their institutions, businesses, and bureaucracies, while the Burmese themselves became menial servants and landless peasants. This domination destroyed traditional patterns of relationship and authority, replacing them with alien Western forms. Burma’s post-colonial xenophobia grew in part out of the disruption of culture and the psychic wounds of subjugation developed during this period. The Japanese invasion during World War II served only to reinforce Burmese opinion that it was best to keep foreigners out.

Following World War II the Burmese elected Aung San and his party to lead their first parliamentary democracy. In 1947, three months after the election, Aung San was assassinated.

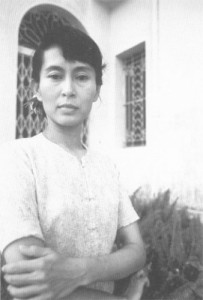

The nation grieved for its promising young leader, whose daughter Aung San Suu Kyi would develop into a leading political figure. On October 14, 1991 Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “because of her nonviolent struggle for democracy and human rights.”

Aung San’s Successor, U Nu, a deeply religious Buddhist, administered Burma for fourteen years. He developed a form of social democracy by means of which he attempted to govern a splintered and factionalized country, balancing pressures from disaffected minority groups and the increasingly powerful military.

The rule of U Nu came to an abrupt end in 1962 with an overnight coup staged by General Ne Win and his military. Since then, Ne Win has controlled Burma. His rule, both authoritarian and inept, has led a once prosperous Burma to political chaos and the brink of bankruptcy. Several times during the past thirty years groups of students and monks organized protests against the regime, never succeeding and often sacrificing their lives in the process. Finally, in 1988, the people mobilized and nearly brought the government down.

By 1988 conditions in Burma were unendurable. Ne Win had mandated several demonetizations that obliterated life savings. He had so mismanaged the economy that he reduced a once prosperous and proud nation to number four on the United Nations’ list of the world’s ten “least-developed” nations. He misallocated monies earned from selling natural resources in order to create military privilege and elitism. In a country that had never known hunger, food and jobs became scarce; it is estimated that today forty percent of the population live in poverty. Opportunities for educated professionals ceased to exist despite the strong emphasis in traditional culture on higher education. The ethnic minorities faced obliteration by a government hungry for their land and its riches.

Demonstrations began after a student incident in 1988 provoked excessive military response. Protest spread rapidly. Between March and September millions of people took to the streets to demand freedom.

In a move that prefigured the military violence in China’s Tiananmen Square in 1990, Ne Win responded swiftly. Witnesses saw thousands of citizens, including large numbers of children, monks, and university students, murdered in the streets or bludgeoned and dragged off to prison. Rivers in Rangoon ran red with the blood of protesters. Week after week for half a year, nonviolent demonstrators, Buddhist and Burmese, faced a brutally violent military, who were also Buddhist and Burmese.

On September 18, 1988, the military reasserted control over the nation in revolt and formed itself into the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) to establish emergency measures that restricted every movement and initiative of the people. Universities and medical schools were shut down, and all foreign observers were ordered to leave the country. Government control of the people became absolute.

In the years since 1988, civil liberties in Burma have deteriorated still further. Nineteen centers for torture now exist throughout the country and Amnesty International names Burma as having one of the worst human-rights records in the world. Universities and medical schools remain closed, or open only under severe restrictions. Public meetings, or gatherings of more than five people, are forbidden. Neighborhoods where protests occurred have been destroyed, the residents forcibly evacuated to isolated, malaria-infested swamp. Armed soldiers surround monasteries and pagodas. The only press is controlled by the SLORC. The regime has even renamed the country Myanmar, but since this was done over the objections of its citizens, foreigners sympathetic to the oppressed demonstrators do not acknowledge the new name. Civilian courts have been replaced by military tribunals that sentence thousands to prison, or worse, without trial. Even overseas Burmese are not immune; many living in the West dare not speak out for fear of reprisals to relatives inside Burma.

On the peripheries of Burma, the military recently escalated its war against the ethnic minorities. Using money earned from the sale of natural resources, the government buys high technology jungle weaponry, thus destroying the indigenous peoples with weapons purchased from the bounty of their own land. Soldiers pillage and burn ethnic villages, raping and capturing females for sale to prostitution rings and enslaving males as porters and human mine sweeps for the military.

Living in the jungles along with the ethnic minorities are thousands of Burmese university students, who fled certain extermination by the military for an uncertain fate as exiles in an alien environment. Approximately ten thousand of them made their way to border areas, most commonly to the border between Burma and Thailand. In this inhospitable environment, the majority died of malaria, starvation, or military attack. Some made their way across borders to other countries, and three thousand remain hidden in the jungle, where they learn survival techniques from the indigenous peoples. In turn, students organize schools and health clinics. Given the hostile history between Burmans and the minority peoples, these bonds will be important for Burma’s future if the students and their hosts can outlive the present military regime.

Because of the excellent market for high-priced teak, Burma has the world’s third highest deforestation rate. Thai companies buy logging concessions in Burma and clear-cut the forests, leaving no young trees to replenish the species. This causes massive erosion and additionally requires building roads that then facilitate assaults on ethnic villages. Japanese and Western companies purchase the teak from the Thais, which enables the Burmese military to buy more weapons.

The global political and economic community has been cautious in its criticisms, due to the economic rewards of Burma’s exports. However, sufficient pressure forced elections in May of 1990. Despite government harassment, there was an unprecedented turnout. The National League for Democracy (NLD) opposed the military and won eighty-four percent of the vote. However, prior to the election, the NLD leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, was placed under house arrest where she still remains. After the election, most of the duly elected officials and their supporters were jailed without trial. Many were sentenced to twenty-five years in prison.

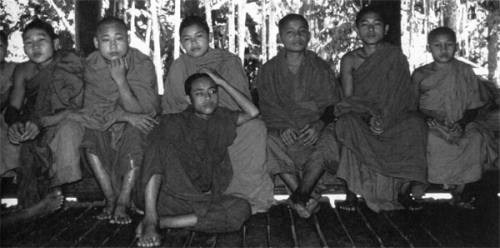

What, then, is the place of Buddhism in this beleaguered country? How do we reconcile Buddhist ethics with Burma’s history? Burma has 300,000 soldiers; it has 300,000 monks as well. Soldiers and monks are recruited from the same villages. Over the centuries Buddhism and militarism have always coexisted.

In the days before the British occupation, the Burmese sangha, or community of the ordained, and Burma’s kings evolved a mutually beneficial system. The kings gave protection and support to the sangha, which in turn encouraged the villagers to be loyal to the rulers. It was the duty of the sangha to teach the ruler the Dasa Raja Dhamma (Ten Duties of the King). The villagers provided for the daily material needs of the sangha, which, in turn, cared for the spiritual well-being and educational requirements of the villagers.

These interrelationships offered security and continuity but did not challenge the rulers with the discrepancies between Buddhist teachings and military behavior. Although some few Buddhist monks question state-sanctioned violence, Burma is not a theocracy and religious leaders are not central to political concerns. Furthermore, a king or ruler who is Buddhist does not necessarily exhibit Buddha-like behavior. In fact, kings are more likely to have a stronger reciprocal obligation with their military than with the community of monks.

Buddhist teachings for villagers in Burma stressed dana, the generous giving of alms, and sila, ethical conduct. Village Buddhism shapes the life cycle and gives meaning to existence. The villagers put gold leaf on images of the Buddha, make offerings, and gain merit through good deeds. The actual practice of formal meditation, from which substantial transformation of consciousness arises, has not been emphasized in village life. Some contemporary monks note that the complete teachings of Buddhism must be practiced if violence and aggression are to be be uprooted.

With the arrival of colonialism, the king-monk-villager relationship, with all its merits and faults, was shattered. The British neither respected Buddhism nor understood its traditional interdependent sources of support. Western-style government-supported schools replaced the education offered by monks. Thus, the monks lost their power both as educators and as negotiators between the people and their rulers. Some sangha members, stripped thus of their traditional roles, found themselves allied and activated with the students in the quest for nationalism and freedom from British rule.

Such politicization of monks is rare in the history of Theravada Buddhism. Nevertheless, it was apparently accepted by many of the Burmese laity who cheered the attempt to oust the colonizers. One monk, U Wizaya, died in jail during a hunger strike in 1929. Another, U Ottama, strongly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, was convicted of incitement to rebellion and died in prison in 1939. This period paved the way for the present Ne Win era, when monks together with students and pro-democracy activists rally once more for freedom.

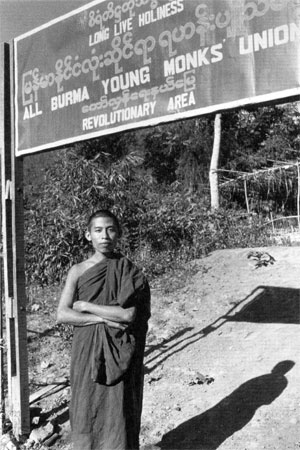

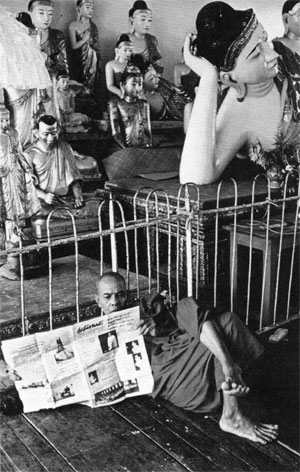

Still Buddhism survives. In the ancestral village temple, silent monks walk barefoot in the early morning collecting alms. In some few monasteries, intensive meditation practice is taught to a small number of Burmese and Westerners. Other monks are demonstrating, going to jail, refusing to accept alms from the military, developing their own forms of nonviolent resistance, and organizing with the students in Burma’s border jungles under the name of the All Burma Young Monks Union. At the same time, the military government infiltrates the monasteries, discrediting monks who oppose state violence and elevating the status of those monks who cooperate with the regime. Ne Win’s military is even building an elegant pagoda, ironically reminiscent of the pagodas in Pagan constructed by slaves nine centuries ago.

Buddhism in Burma has survived empires, colonialism, and war. However, Burmese Buddhism has not been any more triumphant than most other world religions in creating a nation-state based on its core teachings. Despite a 2,500-year presence of the dharma in Burma, the minds of rulers and warriors remain untamed, turning as always to rule through violence. Burma and Burmese Buddhism may have made some progress in the millennium since slaves built the monasteries, but in the long cycles of Burmese suffering, we still await a just Buddhist state.