Tamding Tsetan is a multi-instrumentalist, tattoo artist, calligrapher, and political activist whose work seeks to preserve his Tibetan heritage while constantly challenging the norms attached to it. Born to a nomadic life in the village of Windu in the Amdo region of Tibet, Tsetan ended up fleeing the country in 2002 in a dangerous trek across the Himalayas.

As a refugee in India, he attended the Tibetan Children’s Village in Dharamsala, where he learned English and trained briefly in painting thangkas [Tibetan scroll paintings]. After school, he joined the Aku Pema Performance Art group, with whom he toured India spreading Tibetan music and dance. He then worked for two and a half years as a modern artist and music teacher at the Dharamsala-based Norbulingka Institute, which preserves Tibetan art techniques.

Now, Tsetan lives in Portland, Oregon, where he works as a tattoo artist and performs his blend of traditional and original Tibetan music, which can be found on his album Open Road.

Tricycle spoke with Tsetan over the summer while he was in New York City for a concert and calligraphy demonstration at the Tibet House.

Hiking the Himalayas, you have said that you went days without food in freezing conditions. Was your experience typical for a refugee fleeing Tibet?

Every person who escapes from Tibet is going to have a completely different story—because there’s no map. You just cross the Himalaya—you see the mountain and cross it. One day when we were crossing, I spotted Chinese soldiers, who would have arrested us on the spot. We had to change our route. That’s why there can’t be just one path that you follow through the mountains, because if you did that, the army would know where you’d be. At another point, we spent three days going up one mountain only to see at the top that we could have gone around. It ended up taking us 43 days to cross, when other people crossed in a week. That’s what happens when you don’t have a map.

We also had to cross in the winter because the army is less active then. By the time I got to Nepal my skin was cracked, and then it became infected. I still have scars on my face.

When you got to Nepal, you weren’t in the clear yet. You still had to avoid authorities because they might send you back or just rob you.

They did rob us. But we planned for that, because we had heard stories about it. At the same time, we wanted them to take us to the police station because that’s your best chance of getting refugee status. We wanted the police to take us to the refugee centers in Kathmandu. The problem was that sometimes they would just rob you and then kick you back out onto the street.

So we tried to get them to arrest us, and they took our stuff. But I brought special underwear with a zipper that I used to keep 300 Chinese Yuan ($44) and brass knuckles for protection. So by the time I made it to India, I still had some money. I had saved it for an emergency, but when I got there, I ended up using it to buy a guitar—my first guitar.

But at that point you had already been playing music in Tibet—playing the mandolin, right?

Yes. I first heard the mandolin on the radio, and it was always really beautiful. So one day, when somebody threw away a guitar with a broken neck, I took it to my grandfather, who was a woodcarver. He helped me make a mandolin neck. I didn’t have strings, so I used the brake lines from a motorbike. After a year, I had learned how to play on that two-string mandolin.

Playing on a brake line must be so hard on your fingers.

I don’t think I could do that now. The strings weren’t even straight. When I was older, around 16, I wanted to buy a real mandolin. I was working for my uncle as a shepherd. Even though they were his sheep, he didn’t know them as well as I did. So I started trading the big sheep for little sheep to get some extra money. My uncle never noticed because I’d come back with the right number of sheep.

Eventually I had enough saved up for a mandolin, but when I brought it home, my family asked, “Where did you get it?” I told them that somebody lent it to me, and they left me alone. But from then on I needed to practice it in secret.

I did the same thing with a pair of baggy pants that were really fashionable among musicians. I couldn’t wear them in public because people would ask questions. So I would walk to the top of a mountain and put them on. Then I would take out my mandolin and pretend like I was a real musician—but no one was around to see except the sheep.

The first time I played in front of anyone was when I was 17. I had studied one song really hard. The people I played for loved it so much that they kept shouting, “Again, again!” That was also last time I performed at home, because a couple months later, I moved to Lhasa and then to India. It’s been almost 20 years since I’ve been home.

Did you bring the mandolin with you?

I had to leave that one at home, but I bought a different mandolin in Lhasa and brought it with me when I left Tibet.

I had been working as a chef in Lhasa, and I knew that I would be leaving, but I didn’t know when. We couldn’t plan when we’d go because then someone could find out. There were 49 people planning to go to India, and if anybody got caught, we’d all get caught. Then we would be put in jail and beaten. China didn’t want people fleeing because they wanted the world to believe that it was a great country and didn’t want us telling people what it was really like.

One day, someone came to the restaurant and said, “You have to leave in 30 minutes.” I told the owner of the restaurant that I had to go pee and left the country.

At some point when we were crossing the Himalayas, the mandolin came out my bag and started sliding back down the mountain. It seemed like it was sliding for 20 minutes. Everybody told me, “Leave it.” But I still climbed back down and got it. Most of the people left without me. Only four friends waited. But that’s how much I love the mandolin.

Why did you leave Tibet?

When I left Tibet, I just wanted to study English. I didn’t even know about the politics. When I got to the refugee center in Nepal, that was the first time I saw the Tibetan flag. They showed me a movie called “Cry of the Snow Lion,” and then I began to understand what was going on.

When I was young, my grandmother used to say, “When I was growing up, we didn’t have food. We had to eat grass and bones. You guys are lucky; you were born in a good time.” So she would tell me that China is doing great now because at least we weren’t starving. The news said that we have a great country, too. The TV and movies would talk about how Japan was demonic. People would say that Japan had a ghost army, but China was a happy country.

But that probably wasn’t lining up with your experience.

When I came to India, that’s when I learned the truth, but people in Tibet still might not know. I only knew my father for one year when I was 16, but he used to be in the Chinese army. If he heard me talking about Tibetan politics he would say, ”That’s all bullshit. It’s the Tibetans who are making the problem.” He believed Chinese TV, which pushed the idea that Tibetans were stupid, and China can make us smarter.

Meanwhile, the Chinese won’t give you a real education. If you want to go to a good school, it will be Chinese-run, and their education is very nationalistic. Every story they tell you is about sacrificing yourself for the nation. And they would made you sing patriotic songs.

At the same time that you were singing those anthems, dunglen [a style of lute music that translates roughly to strike and sing] was popular. The dunglen music videos I watched seemed to be uniquely Tibetan and were filled with images of the Dalai Lama and the Himalayas. What did that music mean to you?

So before dunglen, there was already a Tibetan dranyen, which is a long, three-string instrument. That was used for a long time. Dunglen is much newer. The person who created it, Dubey, died just two years ago. He recorded more than 300 cassette tapes worth of music.

He spent his whole life talking about the environment, Tibetan culture, Buddhism, the lamas, and so on. Not all dunglen is like that. But Dubey is still the most famous dunglen musician, and he was able to command the same amount of respect as a lama.

He wrote one song from the perspective of a baby deer, asking why you, the listener, killed his mother. You are a human with a powerful weapon, and you used it on a defenseless animal. And now I’m mourning in the grassland, and I’m all alone while you eat my mom. At the time, Tibetan nomads always had a gun to defend against animals, like wolves. But they would also use it to hunt. Then after Dubey wrote this song, many people stopped hunting.

When these songs came on the radio, it was really impactful. I remember I would sing the songs I heard, and a lot of old women would start crying.

Do you still sing a lot of traditional music or dunglen?

I do both. Right now, I’m trying to do mostly nomadic music. I’ve started performing some songs with just my voice and a drum that I made, which is like how a nomad would do it. I also play the mandolin, dranyen, guitar, and flute—the flute goes everywhere I do.

You seem to have a lot of reverence for your culture, but at the same time, you like to put your own spin on it. How do you preserve Tibetan culture while allowing it to change?

That’s the main thing I wanted to do with my album. Everything is new—lyrics, melodies, everything. Because whether it’s good or bad, at least it’s mine. I want Tibetan people and my generations to feel free to create their own art. Often, Tibetan musicians would take a melody from a Chinese song and then add Tibetan lyrics. I wanted to do something different.

So, for example, I wrote a heavy metal song, because there’s no Tibetan metal bands. A lot of my music before that was sad or emotional. But metal had a different energy to it. It makes you want to stand up and say, “We can do this.” That song was also inspired by the violence on March 14, 2008, after Tibetan Uprising Day.

How did the refugee community react to your music?

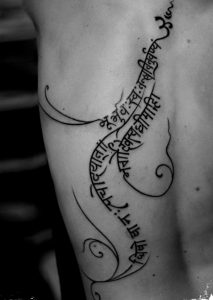

It’s always hard to do something new. The first time I put Tibetan text on a T-shirt, people said, “Oh, you cannot do that. The text is very precious. You cannot wash it with underwear.” But now, a lot of people make T-shirts with Tibetan text. Tattoos were very hard in the beginning, too.

How did you start doing tattoos?

Before tattoos were common in India—the first tattoo convention was in 2010—people were doing it in the street. It was very dirty. They would use one machine for 100 people without really cleaning it.

One day, a friend of mine gave me a tattoo using a sewing needle and ink. It was painstakingly slow. So I made a machine using pieces from a cassette player, a ballpoint pen, and the battery pack from a keyboard. The big advantage was that I was able to change the needles, so it was a lot cleaner. I started doing tattoos for some of my friends, and they liked the work that I did.

In 2003, I opened a hair salon—because there were no Tibetan hairdressers in Dharamsala—and in the back I had a tattoo shop. Then in 2006, I met a tattoo artist from Seattle, and she showed me how to make a modern tattoo. A year later she bought me a tattoo gun, and that’s when I started to do it as a real professional.

Related: The Outlaw Buddhist Art of a Korean Tattooist

I realized how important it was for there to be a Tibetan tattoo artist when I saw a Japanese tattooist who was doing Buddha images and Tibetan words on people’s asses. To this day, the most important thing on my website is that it says, “I don’t do Buddha’s image” and “I don’t do tattoos for monks.”

Why not?

I’m not against a monk getting a tattoo, but I won’t personally do it. To me, monks are very clean or pure. So it doesn’t look right to me—the image of a monk with a tattoo sitting on a raised chair. Maybe in the future that will be normal—and I think in Thailand there might be a culture of tattooing monks—but that’s not my culture.

Monks are guides and teachers. They shouldn’t necessarily be doing what the community does. We have sex and have kids, but monks can’t do that. Otherwise, they’re not monks anymore.

Have a lot of monks asked you?

Many times. They always ask why I won’t do it. And I say, “Because it’s my choice. You can do it somewhere else.”

Why won’t you tattoo images of the Buddha? Do you tattoo images of other deities?

I trained for a while in painting thangkas. Thangkas have a lot of rules about the Buddha’s image, but they aren’t as strict about the other figures. There are other things that I pull from thangkas, such as the clouds or the way they depict animals.

Related: A Thangka Painter for the 21st Century

But never the Buddha. Not because it’s a sin, but because I’m a student of the Buddha. And I refuse to sell the Buddha. But again, if someone else wants to do it, that’s fine.

How has calligraphy influenced your tattoos?

Calligraphy has really helped. It has always been a very creative outlet for me, but one thing I started doing recently is taking Tibetan writing and using it to draw yaks, donkeys, goats, and so on. I want the younger generation to see all the things that our text can do and love how beautiful it is.

Do you meditate or recite mantras?

Not so much. My family is ngakpa, or shamans. I used to read scriptures every day when I was young. My hair was cut short with a long ponytail on top, which meant I was going to be a shaman in the future. I ended up cutting it off when I was 17 because people would pull it.

Do you see what you’re doing now as related to being a shaman or serving a similar role of being a teacher?

I’m not a teacher, and I don’t want to be one. And I’m not trying to mix music and religion all that much. But what I want to do is express the elements of nomadic and shamanic music, which is a large influence in my flute style.

I want to capture the natural mantras that we have in nomadic life. Nomadic music is connected with the earth. For example, where I’m from, nobody plays the flute in the winter because we believe animals are sleeping or meditating. Then in the summer, we play music as a way of saying, “Hey, wake up. It’s summer.” And what we’re singing is a type of mantra. So music and nature are very connected that way.

Sometimes a woman with a really high voice will go to the highest mountain and sing mantras. She’s not a monastic, and it’s not for any audience. She just sings for herself. And you can hear them from very far away—it’s just the sound of the grasslands.