Dick Dorworth is working on a typewriter, cross-legged on a thin mattress inside a handmade redwood slide-in truck camper. The year is 1974. Sheets of paper are stacked beside him, and woven tapestries hang from the open back doors. A pair of leather hiking boots is tucked in the truck bed beside camping gear. Dorworth’s dark hair and beard fall past his shoulders; his glasses are tight against his face. In the background, ponderosa pine boughs hide Yosemite Valley’s sheer granite walls.

National Geographic photographer Galen Rowell took this image of Dorworth, singularly focused on the work in front of him: Night Driving. This seminal coming-of-age tale is a window into the 1960s and ’70s counterculture fringe of climbers, skiers, and vagabonds and the drugs, drinking, and sex they imbibed. Mountain Gazette published all 100 pages of it in 1975, alongside a short essay by Edward Abbey, the two pieces taking up an entire issue.

“It became an instant cult classic, a talisman and a benchmark for those who fancied themselves hardcore,” wrote fellow climber, writer, and Buddhist Jack Turner, in an introduction to a later edition.

Night Driving was based on the real thing. Dorworth, who turned 80 in October, broke the world speed skiing record in 1963, going 106 miles an hour on metal skis and leather lace-up boots on an icy Chilean mountainside. He went on a 6,000-mile road trip from California to Argentina to climb Cerro Fitz Roy in 1968; his team—among them Yvon Chouinard and Doug Tompkins, founders of Patagonia and The North Face, respectively—made the third ascent of the 11,020-foot rock spire. And between 1957 and 1971, Dorworth fathered five sons by five different women. He didn’t meet or know about two of those sons until he was nearly 60. I first met Dorworth in 2006 at Practice Rock, a climbing area south of Bozeman, Montana, where I live and he spends summers with his partner, Jeannie Wall. Since then, we’ve become friends. They winter near Sun Valley, Idaho, where Dorworth—a member of the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame—still skis six days a week.

In mountain towns such as ours, Dorworth is a living legend known both as the madman he once was and the kind, loving Zen philosopher he is today. He is a child of his generation, his story one of redemption as well as contradiction. Never chasing commercial success or fame like some of his contemporaries, Dorworth followed his own path. It always led to the mountains.

There, and later in the zendo, Dorworth shifted his way of being in the world. One foot in front of another, one breath at a time, he found peace.

When he was 7, Dorworth and his parents moved to the south shore of Lake Tahoe, Nevada, to work for his aunt and uncle, who owned Harvey’s Wagon Wheel Casino. His mother was a cook, waitress, and change girl, and his father did bookkeeping and odd jobs. After class at the Zephyr Cove one-room schoolhouse, Dorworth would strap on his wooden skis and sidestep up the hill behind their house, lapping it until dark. He leapt off jumps, practiced slalom technique on a race course made of willows he’d cut and stripped with an axe, and toured the hills above the cove.

“I learned to cope with and then cherish solitude in action on skis, and those times were among the happiest of my childhood,” he wrote in The Only Path, a memoir self-published in 2017.

A natural athlete, he found joy in skiing—in the movement, in the discipline of practice, and in the mountains. It was also an escape from his parents’ difficult marriage.

While Dorworth’s father was deployed with the Navy during WWII, he had an affair with a woman who then died while he was overseas. He returned to a wife and 6-year-old son, living at home with resigned acceptance. Dorworth’s mother never forgave her husband. Dorworth himself didn’t find out where the resentment came from until he was almost 50.

His parents dulled their misery with alcohol, often drinking until dawn in casinos and bars around Tahoe, Reno, Carson City, and Las Vegas. Dorworth spent those nights in the back seat of the family car.

“Sometimes it was cold,” he wrote. “Always it was lonely. Sometimes it was scary. And I always hated it.”

When sober, his parents were caring and affectionate. They bought him ski gear they couldn’t afford and drove him to races around the West. Herself a fan of pop fiction and mysteries, Dorworth’s mother gave him the essays of the 16th-century French philosopher Michel de Montaigne, crime novels by Mickey Spillane, and everything by Mark Twain and Jack London.

Dorworth finished Reno High School and entered the University of Nevada, Reno in 1956, a time he has described as “an insipid era of saccharine shallowness and sterile hypocrisy that the ’60s would none too soon strip naked.” He studied English and journalism, ski raced, partied, and read Faulkner, Snyder, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Hemingway. He graduated in 1963 with a BA in English.

“Skiing and the mountains gave me a place to put my anger about my family dynamics and the disruption in life caused by WWII,” Dorworth told me. “[Both] were the beginning and the path of spiritual searching, which eventually took me to Zen.”

Although he was an all-American college ski racer and a member of the first U.S. National Development Team, Dorworth never made it to the top of that game, in part because he hated the politics and favoritism of sanctioned ski racing. The niche pursuit of speed skiing, on the other hand, had none of that. It was pure. All he had to do was survive.

“He was a very bright, intuitive, creative guy,” said C.B. Vaughan, a racer who spent three months preparing the speed course in Chile with Dorworth and, incredibly, tied the record that same day. “He was always interested in everything and anything.”

After he retired from racing in 1965, Dorworth began a 30-year career as ski coach and instructor, which included a winter coaching the U.S. Men’s Ski Team and four as director of the Aspen Mountain Ski School in Colorado. In 1966, at age 28, Dorworth started graduate school. The plan was to become an English professor, but he left after a year, bored and exasperated. The country’s fault lines were spreading amid Vietnam and civil rights protests. Dorworth was still lugging around angry childhood baggage. He’d been dropping lots of acid. He needed something to believe in.

He found climbing.

In spring of 1968, he visited Yosemite Valley at the invitation of Jim Bridwell, whom Dorworth had instructed for free that winter in Squaw Valley. King of Yosemite’s climbing scene, Bridwell was the visionary behind Yosemite’s most cutting edge routes at the time. After a month in Bridwell’s tutelage, Dorworth loaded into a Ford Econoline van headed for Argentine Patagonia.

The crew—Dorworth, Chouinard, Tompkins, and Lito Tejada-Flores, who made a film about the adventure—called themselves the Fun Hogs. They surfed their way south, picking up British ex-pat Chris Jones in Peru, and then skied two Chilean volcanos, Llaima and Osorno. On Fitz Roy, they spent 31 days in snow caves waiting out storms. Photos show Dorworth carrying a massive pack across a glacier; journaling in a snow cave, brow furrowed; and holding a red “VIVA LOS FUN HOGS” banner on the summit with Tompkins and Chouinard, surrounded by sky and clouds.

“He was great to have on the trip because he’s a storyteller,” Chouinard told me, adding that although Dorworth had very little experience as a climber at the time, he was an asset to the team. “He was a great athlete. He had no fear. We’d tell him what to do and he’d do it exactly, and really safe.”

Over the next three decades, Dorworth established first ascents from the sheer 2,200-foot northwest face of Half Dome in Yosemite to Idaho’s City of Rocks; climbed in Europe, Asia and the Americas; and guided around the Western United States.

And he wrote about it. One of the first to explore human relationships on the vertical stage—and not just the facts of a climb or the glory of a summit—Dorworth became an influential thinker in the ’60s and ’70s, Chouinard said. “[Night Driving] kind of broke the mold.”

Some of Dorworth’s work is so visceral, I still feel it years after I’ve read it. In this extract from The Straight Course, one of his five books, he describes breaking the world speed skiing record:

Acceleration like a rocket launched in the wrong direction. The sound of endless cannons, moving closer. Irreversible commitment.

The soles of my feet said this was the one. My eyes saw the transition and peaceful flat, far, far away. My body, appalled at the danger in which it had been placed, acted automatically, reluctantly perhaps, but with an instinct and precision that preceded the mind which put it there. My naked mind had finally gotten hold of the big one that had always gotten away.

A social critic influenced by the 1960s New Journalism genre, Dorworth asks big, existential questions, his long-winded prose unconstrained by linear time. Although he is pessimistic about the current state of the planet, a rhythm—unmistakably Beat and more powerful than his words—runs beneath his writing, tapping out a reverence for nature and resolute belief in the human spirit.

Dorworth wrote for magazines including SKI, Powder, and Mountain Gazette, and his topics ranged across the skiing world. He profiled filmmaker Warren Miller, in whose films Dorworth starred; reported on a 1982 avalanche that killed seven people in Alpine Meadows, California; and wrote a brutally honest account of the personal dynamics on a 1981 expedition to ski 24,757-foot Mustagh Ata, in China. At home in Sun Valley, he worked as both reporter and columnist for the Idaho Mountain Express for 20 years before switching to the Weekly Sun, where he’s been for nearly a decade.

In the zendo, Dorworth shifted his way of being in the world. One foot in front of another, one breath at a time, he found peace.

Dorworth had the chops to make it big, but he never promoted himself or schmoozed, and he wasn’t interested in being edited. Instead, just as he did everything else in life, he wrote on his own terms.

An old rumor is still kicking around around mountain towns about a Sun Valley bumper sticker that supposedly read: “Honk If You’re Dick Dorworth’s Son.” While the sticker never actually existed—it was just an offhand joke by a ski buddy—the story stuck, much to Dorworth’s chagrin.

The sons, on the other hand, are flesh and blood. Three were born before he was 22, although he only knew about one, Scott, born in 1960 to Dorworth’s first wife. The couple had almost broken up but decided to make a go of it when she became pregnant. With a leg badly broken in a ski racing crash, Dorworth took a job in Stanford’s Sociology Department. But, as he wrote, he was unable to “pay in the coin of conformity.” When Scott was 3 months old, Dorworth’s wife drove her husband to South Lake Tahoe and left him beside Highway 50 with a suitcase, a typewriter, and less than $100.

The only son Dorworth helped raise was the youngest, Jason, who was 2 when he came to live with his father. They stayed in the old redwood truck camper at first but soon moved to a cabin in the pines above Truckee, California. Dorworth wrote:

Being a single parent is challenging for the most organized, grounded, stable and socially responsible person. At the time, finding these personal attributes in me was as much a challenge as raising an energetic, bright young boy; and, of course, not finding them in his father was a challenge and frustration for my son.

They spent many days at the crag and ski mountain. When a teacher suggested putting Jason on Ritalin, Dorworth refused, incredulous about the irony of a hippie fighting conservative administrators to keep his kid off drugs.

“He was always kind to me, even if he was firm,” said Jason, now division chief with the Santa Cruz, California, fire department. “He has a pretty fixed ideology about what is right and wrong. I think when he was younger, it got exposed as self-righteousness, but now it’s more self-awareness.”

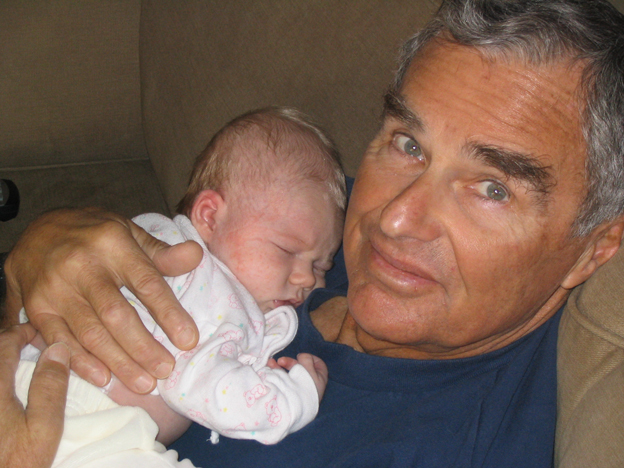

Today, Dorworth is close with three of his sons and their children, and he is friendly with another. One son won’t speak to him. Married four times but never for long, he acknowledges his absence from his sons’ childhood lives, and their mothers’ umbrage.

“I recognize the positive changes he’s made, and yet it’s sometimes still painful and hard to let go of resentment over some of the things that happened,” said Jason’s mother, Jane Badeaux, who married Dorworth when she was 20 and he was 33.

For his part, Dorworth doesn’t dwell on the past, especially on events before he got sober. “A lot of people don’t like it, and I understand that, but that’s their problem,” he said.

When he was 46, something happened that allowed Dorworth to let go: his father told him about the affair. “All of a sudden,” Dorworth said, “this thing I’d been holding, this anger, it simply wasn’t there anymore.” Then, on January 31, 1987, sitting in his kitchen in Albany, California, Dorworth twisted open a bottle of Rainier Beer, drank it, brushed his teeth, and went to bed. He hasn’t had a drink or a drug since.

“Had I been able to let go of all my anger at 20 rather than 48, my life would have been different, but neither would I have learned the lessons I learned. One cannot redo the past or even worry about it.”

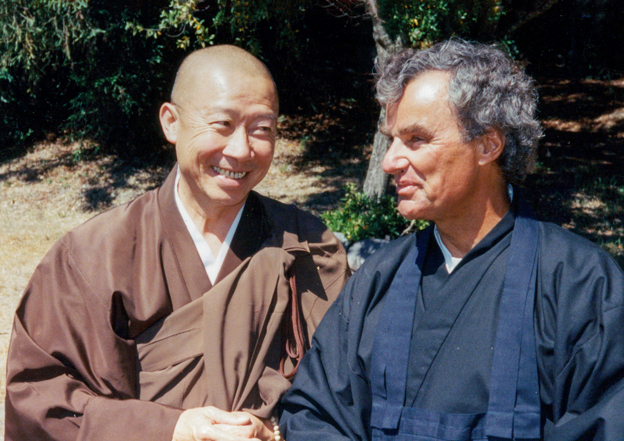

“Skiing and the mountains gave me a place to put my anger about my family dynamics and the disruption of life caused by WWII.”A couple of years later, at age 50, he came down with Pott’s Disease, tuberculosis of the spine that required major surgery. While recovering, he joined a Tibetan Buddhist meditation group in Aspen, Colorado, and when a climbing expedition to Bhutan fell through, he attended a 10-day retreat at the Sonoma Mountain Zen Center in California. With the same intensity and discipline he’d applied to skiing, writing, and climbing, Dorworth dove into Zen. Practicing at the center in Sonoma, he studied under Jakusho Kwong Roshi, a successor in the lineage of Suzuki Roshi.

Buddhism had long been knocking at his door. In high school, he kept a gold-painted ceramic Buddha on his dresser, having no idea what it was; after slaughtering and eating a lamb in Patagonia, he swore off meat at age 30; and in 1980 he had a spiritual encounter in Beijing, during which, he says, statues in a Buddhist temple came to life before his eyes. When Dorworth took his Soto Zen vows two years after the first retreat, it felt like coming home.

But eight years later, a few months after serving as shuso, or head student, at his fifth 30-day ango (training period), Dorworth left the Zen center to practice on his own. Hesitant to describe the details of his departure, he instead points to Soto teacher Reb Anderson’s book Being Upright: “‘Some people, particularly those in the United States, don’t like to be labeled an “ist”: Communist, capitalist, or Buddhist,’” Dorworth quotes. “‘Other people don’t want to get caught up in the institution.’ When you’re a member of an institution, you’re at the call of the leader of that institution. I couldn’t get caught up in the institution. It violated my nature.”

Letting go of the past and practicing Zen created profound change for Dorworth, both immediately and over time. It has allowed him to find love and connect with family in a way that wouldn’t otherwise have been possible.

When he was 56, Dorworth received a letter from a man named Richard McFarland, who explained over six pages why he thought Dorworth was his father. Later, the men spent a week together at Dorworth’s home ski mountain, Sun Valley, Idaho. Even before a DNA confirmation, they were sure of the connection. Overnight, Dorworth was a grandfather.

Soon after, Richard, who now goes by McFarland-Dorworth, helped locate another son, Jeff. “It’s a very unusual family constellation,” said Richard, who was 37 when he met Dorworth and describes him as a mentor figure. Richard said his sons have a more conventional relationship with Dorworth. “They know who their grandfather is, and it helps them make sense of their lives and who they are.”

And then there’s Jeannie Wall, the only woman Dorworth has been with since sobering up: Dorworth both adores Wall and says she’s his karma. A former US Ski Mountaineering Champion and a top outdoor clothing consultant, she climbs and skis 150-plus days a year, leading a life not unlike Dorworth’s own earlier pattern of peripatetic adventure. Despite a 29-year age gap, they’ve been partners more than 15 years and describe each other as soulmates.

At Wall’s home south of Bozeman, a post-and-beam stucco, Dorworth boils water for a cup of Earl Grey and then settles on the couch in half lotus to talk with me for this story. Out the bay window, across the pond, is a view of the Bridger Range. A copy of The Atlantic is open on the coffee table. Dorworth leans in, glance steady as he tells me about climbing with Wall that morning at Spire Climbing Center. Then he shows me his fingers, which are gnarled and bent by a hand deformation called Dupuytren’s contracture. Because of it, he can climb only the moderate grade of 5.8, he says, while Wall still cranks 5.11.

“It’s sad and frustrating to me that we aren’t able to share physical adventure anymore,” Wall said, “but I appreciate the adventures of the mind we still share.” Dorworth pushes her to get outside her mind, she added. “He reminds me to think about things differently, and often—to stop thinking so hard at all.”

Dorworth still travels, both with Wall and to see family and friends, but otherwise he mostly writes, runs, skis, and meditates.

“He lives a simple life, which a lot of us try hard to emulate,” said Yvon Chouinard.

For the past five years, Dorworth has practiced with the Bozeman Zen Group, sitting for an hour at noon five days a week, and attending a weekly Zen meeting.

“I was curious about what drives someone to be in precarious circumstances that require so much concentration and presence of mind but also relaxation,” said Karen DeCotis, who leads the group, speaking about climbing. “That’s just like sitting. You have to make this supreme effort. You have to be attentive, relax, and not know what’s next.”

Dorworth’s dharma name, Sankatsu, embodies that sense of not knowing. Given to him by Kwong Roshi, it comes from a poem by Suzuki Roshi’s son and means “mountain bone.”

“When the clouds dissipate, you see a mountain ridge,” Dorworth explains. “The message of that dharma name is: The clouds between us and reality—when those dissipate, you will see mountain bone.”

One morning after he’s taken a morning trail run, I ask what life questions he still has. He laughs, and then looks at me with playful seriousness.

“Who am I?” he asks. The answer, as Dorworth knows, is in the mountains.

Climbing Mountains in the Zendo

Writing by Dick Dorworth

During my first ango [training period] I was dealing with a recent personal and professional betrayal by an old friend, and I was having a difficult time letting go of my anger, sadness, confusion, and disappointment. I sat on my zafu in a half lotus with a straight back, relaxed posture, hands in dhyana mudra [a meditation gesture], following my breath as well as possible, but inside I was far from peaceful, unattached, or forgiving. I was pissed, and it must have showed.

During one of the breaks Dave Haselwood, who was shuso [head student], came over to me and said with a smile, “It looks like you’re climbing some really hard mountains in the zendo.”

A moment of insight (enlightenment?) lit up my mind, the first awareness of the climbing dharma, so eloquently expressed by Sir Edmund Hillary: “It is not the mountain we conquer but ourselves.” Yes, on the mountain and the zafu cushion and with each breath of daily life, and you can’t take another breath until you exhale the last one, nor can you make another move until the last one is completed.

—2018