The procession carrying the body of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche was heralded by the wails of a lone bagpiper and the slow, steady heartbeat of a deep bass drum, followed by the hoarse guttural cries of Tibetan horns. As a crowd of more than three thousand American students and guests watched in silence, the funeral procession of Trungpa Rinpoche emerged from a fogbound forest at the Karme Choling retreat center in northeast Vermont. The body was carried in a palanquin—a canopied, silk-curtained upright box—and covered with a round white parasol. The palanquin was then lifted into the ornately painted cremation stupa, twenty-five feet high and surmounted with a gold spire.

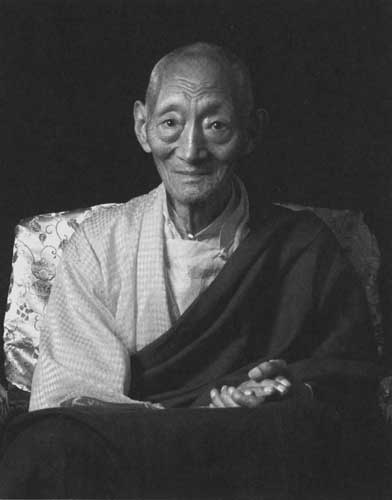

This cremation puja was performed by Tibetan monks led by three of the four regents of the Kagyu school, as well as the late Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, one of Trungpa Rinpoche’s teachers and the head of the Nyingma school. This much was traditional. There were, however, a number of innovations, befitting the cremation of a teacher who had done so much to bring Buddhism, particularly the Tibetan Vajrayana (Diamond Vehicle) into a new country and time. To begin with, the fire puja was also performed by a contingent of American Buddhists. These practitioners performed the same liturgy as the Tibetan monks and lamas, making the same fluid mudras (ritual gestures) with bell and vajra, albeit a bit less gracefully, and they attempted the same visualizations and formless meditations. The Americans, however, chanted the liturgy in an English version. Further, the American tantrikas were nearly all lay persons who had found time to complete the difficult and time-consuming preliminary practices of Tibetan Buddhism while holding down jobs and raising families. They were also evenly divided between men and women. Thus, although everything had been done according to ancient tradition, there were certain changes—changes that were more or less assumed to be natural and necessary to both Tibetan mentors and their American students.

Trungpa Rinpoche had died on April 4, 1987, at the age of 47, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he had moved the international headquarters of the Vajradhatu Buddhist Church. Officially it was said that he had died from cardiac arrest and respiratory failure. That was technically correct, but many people, including some of his most devoted students, thought that his death was related to, if not caused by, his legendary drinking. From the traditional Tibetan point of view, however, Trungpa Rinpoche was not an ordinary man but a bodhisattva, an enlightened master who had vowed to take rebirth in order to liberate all sentient beings. Because of this, all his actions, no matter how problematic they may have looked from a conventional point of view, were to be taken as selfless teachings.

Trungpa himself seemed to have little doubt about either the timing or meaning of his death. “Birth and death are expressions of life,” he wrote in a message read after his death. “I have fulfilled my work and conducted my duties as much as the situation allowed, and now I have passed away quite happily…. On the whole, discipline and practice are essential, whether I am there or not. Whether you are young or old, you should learn the lesson of impermanence from my death.”

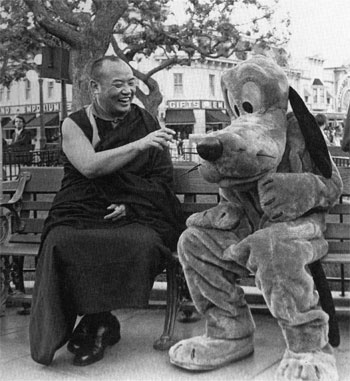

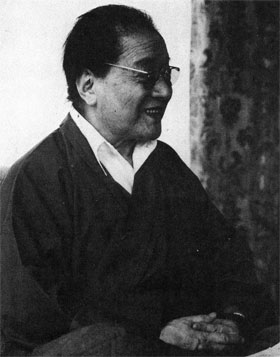

The death of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche did indeed underscore the truth of impermanence. Another era in the history of American Buddhism had come to an end with the passing of many of the first generation of teachers who had been trained in Asia. Trungpa Rinpoche had been preceded by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, the founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, in December 1971; Haku’un Yasutani Roshi and Nakagawa Soen Roshi, who died respectively in 1973 and 1984, had lived long enough to witness the seeds of their Japanese Zen lineages cultivated from New York to Hawaii. His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa, head of the Kagyu school, passed away in Chicago in 1981; in 1984, Lama Thubten Yeshe left his center in Kopan, Nepal, to die among his many Western disciples at Vajrapani Center, in Boulder Creek, California, where he was cremated according to tradition.

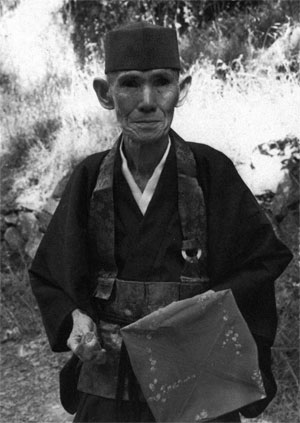

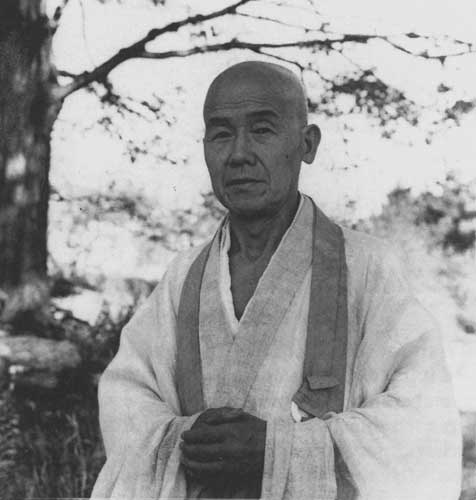

In 1987—the year of Trungpa Rinpoche’s death—His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche, head of the Nyingma School and a terton, or revealer of hidden teachings, died at the age of 82 at his center in Dordogne, France. That same year Deshung Rinpoche, the Sakya lama who had come to Seattle twenty years before, died in Nepal. Two years later, Kalu Rinpoche, the modern Milarepa, died at his monastery in Sonbada, India, at the age of 84. During his four tours of North America, he taught the dharma, as he said, “in a traditional way, without combining it with any other viewpoints,” and he trained many Western lamas in the full three-year retreat. Finally, on March 1, 1990, Dainin Katagiri Roshi died at the Minnesota Zen Temple in Minneapolis. He had come to assist at the Soto Zen Headquarters in Los Angeles in 1963 and had then worked closely with Sunryu Suzuki Roshi in San Francisco. Then, three months before his death, he had performed the ceremonies marking the completion of training for twelve Zen priests, just one Japanese, and eleven Americans.

Because so many of these early great pioneers had left behind American teachers, it was easy to think that American Buddhism had finally come of age. But it soon began to seem that it had entered a period of adolescence—an awkward aggressive adolescence marked by acute growing pains. A number of teachers, American dharma heirs as well as their Asian teachers, fell into a very American trap, namely the abuse of power, particularly in sexual and financial areas; moreover, they found the details of their personal lives subject to an equally American scrutiny and outrage. To many American Buddhists, both students and teachers, it seemed that the meeting of East and West heralded by the heady Sixties and early Seventies had turned into nothing less that a head-on collision.

Signs of trouble first appeared publicly in 1983 at the San Francisco Zen Center, long thought of as the very model of a modern Zen center. Under the guidance of Suzuki Roshi’s dharma heir, Richard Baker Roshi, Zen Center had grown enormously, both in size and influence. Zen Center consisted of three major centers: Page Street, a residential center in San Francisco; Green Gulch, an idyllic farm and lay center nestled in a valley next to Muir Beach on the slopes of Mount Tamalpais; and Tassajara, the mountain retreat center. The community businesses, which included the Green Gulch Grocery, the Tassajara Bakery, Alaya Stitchery, and Green’s, a highly successful gourmet vegetarian restaurant overlooking San Francisco Bay, were all staffed by Zen students, many of whom also lived in either Page Street or Green Gulch.

The initial spark that set off what would soon become a raging conflagration was the revelation that Baker Roshi had been having an affair with a married woman student. This turned out to be the proverbial straw. In the meetings that followed, a number of people revealed other “secret” affairs. In addition, there were also charges of financial improprieties, or at the very least, inappropriatenesses, relating to Baker Roshi’s three residences (in San Francisco, Tassajara, and Green Gulch Farm), his mode of transportation (a white BMW), his extensive library (in triplicate, one at each residence), his art collection, and so on. It was also said that he was using his office to further his own ambitions—that he spent too much time with friends such as Governor Jerry Brown, Esalen director Michael Murphy, and Whole Earth publisher, Stuart Brand, that he had neglected both his own practice and his teaching responsibilities. In short, he lived far too fast and well, while longtime students languished in low-paying jobs that were supposed to be “good for their practice.”

A series of meetings and confrontations followed, but clear communications seemed to elude both the Zen master and the students who had spent fifteen or twenty years practicing to gain clarity of mind. In the end, Baker Roshi left for Santa Fe, and then Crestone, Colorado, where he began teaching a few old and some new students under the auspices of the Dharma Sangha.

Much discussion centered on the faults of Baker Roshi as well as on “the conspiracy of silence” that had allowed many senior students to say nothing even when so much was amiss. But it also became clear that part of the problem had been caused by a characteristically American institution, “the Zen center.” Suzuki Roshi had once remarked that Americans were not quite monks nor laypeople but something in between. His own center, like most other residential Zen centers in the United States, had tried to find a way to integrate the intensity of monastic practice with an American community open to both men and women. Though many of the most serious practitioners were ordained as priests, shaving their heads and wearing robes, they were not celibate, and so as the Zen center grew and matured, so did their families.

In Japan, Zen priests typically marry and take on the job of running a temple after a three- or four-year course of training in a monastery. In America, however, training seemed to go on forever, and after ten or fifteen years it was hardly surprising that many priests and residents came to think of the Zen center as their home and community. There were, in any case, few if any affiliated temples for priests to minister. What, then, did a Zen priest who had lived in a Zen center for ten or fifteen years training and studying do when he or she realized that even enlightenment wasn’t going to solve everything? For some, it now began to seem that they had paid a rather high price for their youthful idealism. They had learned how to sit zazen; they had the security of community; but they had neglected careers and professions. They had not learned how to make their way in the world. They had not grown up.

San Francisco Zen Center members turned, for the moment, to professional “facilitators.” Communications experts and psychologists were invited to give workshops. Some found disturbing but illuminating parallels between Buddhist centers and alcoholic or other dysfunctional families, in which—as one Zen Center member put it—“we’ve learned all too well how to keep silent and how to keep secrets.” In response, ways were sought to make Zen Center more open and democratic. New board members were elected instead of being appointed; and in the biggest departure from tradition, the new abbot, Reb Anderson, was hired for a four-year term.”

Nearly ten years later, Norman Fischer, a Zen priest who now teaches and lives at Green Gulch, reflected on the turmoil. “Teacher-student relationships come out of the fabric of the society that produced them,” Fischer explained in the Buddhist Peace Fellowship Newsletter. “The roshi comes out of the Sino-Japanese-Confucian tradition of ancestor worship. Put that beautiful roshi in the middle of our Freudian-Oedipal-will-to-power tradition, and it is little wonder that people are going to be confused for a hundred years or so.”

Before long, the problems at the San Francisco Zen Center began to seem less of an isolated incident than part of a pervasive pattern. In the next few years a rather large number of Zen teachers found themselves in a similar compromised position. Taizan Maezumi Roshi of the Zen Center in Los Angeles admitted to an affair with a senior student, which led to concern about his drinking, and he entered an alcohol treatment center. Seung Sunim, the supposedly celibate Korean Zen master, revealed a long-term relationship with two students. An elderly, supposedly celibate teacher visiting the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts, was confronted after he made advances to a female student.

As “the conspiracy of silence” was broken, more and more women came forward to reveal problems with a number of other teachers, some of whom denied the accusations or simply remained silent. In 1985, Jack Kornfield published the results of a survey he had made on the “Sex Lives of the Gurus” in Yoga Journal. Kornfield, a highly respected teacher of the Theravada vipassana tradition and the holder of a doctorate in clinical psychology, noted that out of the fifty-four Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain teachers he had interviewed, thirty-four had had sexual relationships of one kind or another with a student. Half of these students reported that they felt that the relationship with their teacher had “undermined their practice and their feelings of self-worth.”

The most shocking news within the Western Buddhist community at large came three years ago when members of the board of directors of Vajradhatu, one of the largest Tibetan communities in North America, instructed teachers in local centers to inform the community that Osel Tendzin, the American regent appointed by Trungpa Rinpoche, had AIDS, had not informed his sexual partners, and that anyone who might be at risk should be tested. “Since none of us believes that Bidyadhara taught ‘magical protection’ against natural cause and effect,” as one board member later put it, “this seemed like a necessary minimal step to take to protect people’s health.” As it turned out, one of the regent’s partners, a young man in his twenties, apparently did contract the virus from him and then inadvertently passed it on to a girlfriend. It was also said that some members of the regent’s inner circle had said nothing, even though they had been aware of the regent’s behavior for some time.

Many people, not surprisingly, reacted with a sense of outraged betrayal. Some reflected as well on the part they had played in this tragedy.

“The Vidyadhara made it clear to his closest students that the regent is not a fully realized person and that it is our responsibility to be clearly critical of him,” one senior student wrote in a letter that was widely circulated. “The recent events have made it clear to us that over the years we have not fulfilled this responsibility. This, our own ignorance and laziness, has allowed things to be brought to a painful point.”

When the news first became known in the Vajradatu community, the regent’s own community, I had the opportunity to meet with Osel Tendzin face-to-face. He was in San Francisco, just having left a long retreat, and was preparing to speak to the sangha at the local center in Berkeley. Sitting across from him in a living room, with four or five other close and concerned students present, I asked, “So what happened?” His answer was direct and spontaneous: “I was fooling myself,” he told me. As we discussed the situation, he was open and frank, but when he addressed a closed meeting of the Vajradatu sangha the next day, though he expressed “tremendous remorse at any pain I may have caused,” he was still careful not to use the “A” word, explaining that members of the press might be present. “Thinking I had some extraordinary means of protection,” he said, “I went right ahead with my business as if something would take care of it for me.” As for explaining how such a thing could have happened, he remained inscrutable. “It happened,” he said. “I don’t expect anybody to try to conceive it.” In a subsequent letter to the sangha, he wrote, “As the Lord Buddha said, there is no fault so grievous that it cannot be purified.” Many students, including the board of directors, asked the regent to withdraw from teaching and the leadership of Vajradhatu. He refused. “To withdraw,” he said, “would violate the oath I took with my guru, and it would also violate my heart.”

The sangha itself was deeply divided. There were those who wanted the regent to resign or be removed by the board of directors. Others thought that he had expressed sufficient remorse and that it did no good to blame or “demonize” him.

Still others suggested that the regent’s plight was not unconnected to Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom” tradition, which included outrageous and unconventional behavior as part of its teaching repertoire. When the board of directors consulted Tibetan elders in Nepal and India, they suggested a traditional Tibetan solution: they advised the regent to go into retreat. For more than a year, continual turmoil reigned. The regent did take up residence in Ojai, California, along with his family and a band of loyal students, but he continued to act as both spiritual and administrative head of Vajradhatu. Consequently, two Vajradhatus now existed, one in Halifax, where the board resided, and one in Ojai. When the regent and the board of directors blocked the community’s newspaper, The Vajradhatu Sun, from covering “the current situation,” which by then had been reported in The New York Times as well as in many other papers, students published an “independent” journal called Sangha.

In the end, the regent did finish his days in retreat. On August 26, 1991, the morning after Osel Tendzin died, Osel Mukpo (Trungpa Rinpoche’s eldest son) was appointed spiritual leader of Vajradhatu. The Sawang, as he was called, who was twenty-seven, returned to India in July of 1991 hoping to gain entry to Tibet in order to receive the complete cycle of the Surmong teachings at the monastery his father had left thirty years before.

As painful as it has been, the unraveling of institutional Buddhism has resulted in a valuable re-examination of the place of Buddhist practice in American society. At the very least, such problems have cut through romantic projections and thrown American Buddhists back on their own meditation cushions.

During the Eighties it began to look as if anyone in a position of power—clergymen, therapists, doctors, lawyers, teachers, and politicians—might be tempted to abuse that power. As Peter Rutter, M.D., writes in Sex in the Forbidden Zone, “Sexual violation of trust is an epidemic, mainstream problem that essentially reenacts within the professional relationship a wider cultural power-imbalance between men and women.”

Viewed within this larger context, the “fall” of a teacher turns out to be rich in spiritual lessons. It brings one back to the critical self-awareness and self-reliance crucial to the teachings of the Buddha, who said, “Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. Do not believe in anything simply because it is found written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of all, then accept it and live up to it.” Zen teacher Yvonne Rand says this quote should be “tattooed on our eyelids.”

The general disillusionment also made practitioners reflect on the difficulties of the path itself. Every level of spiritual insight seemed to cast a corresponding shadow. The closer one got to the heart of the matter, the more furiously the forces of ignorance and habitual pattern fought back. Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, was tempted by both the demons and the daughters of Mara just before he broke through to his final, complete enlightenment.

A little bit of enlightenment, Western Buddhists were finding out, could be a dangerous thing, especially if it led to a feeling of transcendental invulnerability. No wonder Bodhidharma had warned: “one who thinks only that everything is void is ignorant of the law of causation.”

The responsibility for both teachers and students, then, is not to judge and condemn but to work on themselves and to help each other dispel the clouds of ignorance in order to uncover their common, original enlightenment. Easier said than done, of course. But the tradition goes all the way back to Shakyamuni. The Vietnamese teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, one of the most consistent voices for reconciliation, told the story of the pirate Angulimala, who believed he would gain all he desired by stringing a necklace made out of the knuckles of a hundred hands. When he encountered the Buddha, he was filled with remorse, but he felt it was too late for him to change his ways. “It is never too late,” the Buddha replied. “The ocean of suffering is immense, but as soon as you turn around, immediately you can see the other shore.”

Reflecting on the problems of American Buddhism in the 1980s, the Dalai Lama has emphasized that it is important for students to test their teachers for five, ten, or even fifteen years. “Part of the blame lies with the student, because too much obedience, devotion, and blind acceptance spoils a teacher. Part lies also with the spiritual master, because he lacks the integrity to be immune to that kind of vulnerability.” He recommends never adopting the attitude toward one’s spiritual master of seeing his or her every action as divine or noble. “This may seem a little bit bold, but if one has a teacher who is not qualified, who is engaging in unsuitable or wrong behavior, then it is appropriate for the student to criticize that behavior.”

When a reporter asked him if he had any observations to make about the future of Buddhism in America, the Dalai Lama said, “the teaching aspect will always remain the same because the origin is the same. But the cultural aspect changes. Now you see Buddhism come West. Eventually, it will be Western Buddhism. That, I think, is very helpful—that Buddhism become a part of American life.”

And so it is. American Buddhism is hammering out its own shape: an emphasis on householder instead of monk, community instead of monastery, and a practice that integrates and makes use of all aspects of life, for all people, women as well as men. But whatever the shape taken, the shining well-worn gold of the Buddha’s teaching remains the same: the Four Noble Truths—the fact of suffering, its origin, cessation, and the path—and the daily attention that puts it all into practice, again and again and again.

♦

“The Changing of the Guard,” is excerpted from the third revised edition of How the Swans Came to the Lake, coming out next spring from Shambhala Publications, Inc.