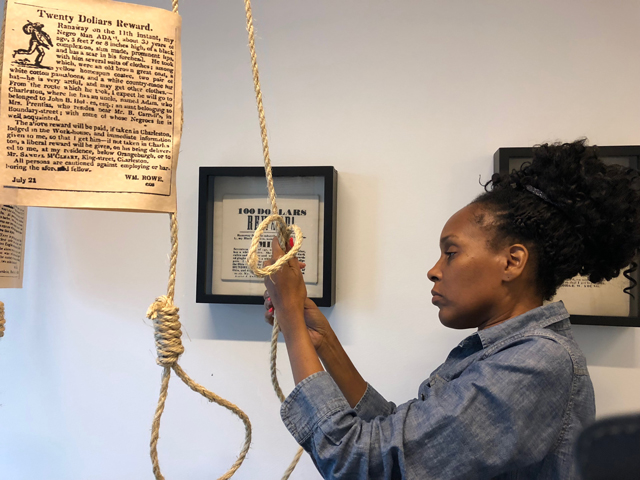

“$100.00 reward. Ran away from the subscriber’s farm, near Washington, on the 11th of October, negro woman Sophia Gordon. . . . I will give the above reward, no matter where taken and secured in jail so that I get her again.”

So reads a typical ad for a runaway slave, featured in artist Aretha Busby’s installation Tolerably Black. She screen-prints the ads by hand onto cotton muslin and frames them in black shadow boxes or attaches them to hanging nooses, also handmade. The cotton is a reference to the industry for which many slaves labored. “They were giving their lives to the fabric,” Busby said, “and I wanted the fabric to give back to their memory.” The nooses are a reminder of what often became of those who ran away repeatedly.

With the project, Busby hopes to give meaning to the lives of the runaway slaves whom history has forgotten. Busby is herself a descendant of a runaway slave who made it to freedom in Canada. “These people were the foundation of my existence here,” she said.

It’s a history that not everyone is comfortable dealing with. As part of the installation, Busby dresses in period costume to interact with visitors, creating a space for open conversation that sometimes leads to pushback. Born into a family that practices in the Nichiren Buddhist organization Soka Gakkai International, she sees the dialogue, approached with a compassionate heart, as part of her Buddhist practice.

Tolerably Black was most recently shown at Brown University in November 2018. Busby has also presented it to elementary schools in New York and New Jersey, and at press time was planning presentations to coincide with Black History Month in February.

—Emma Varvaloucas, Executive Editor

How did Tolerably Black begin? I was trying to learn banjo. There was a Southern band I was interested in called the Carolina Chocolate Drops, and on their website they had a runaway slave ad that said “Looking for my wench.” We’ve all seen runaway slave ads before—I’d like to think so, anyway—but for some reason I had never read one with the same heart. Perhaps it was because I was trying to connect to this music at the time. I looked at it and thought about my great-great-great-great-grandmother, who was a runaway slave. What would her ad have looked like? It started me on a journey.

I started researching the ads and collecting them, and as I was doing that I began thinking that something needed to be done for the people in them. There’s no ending to any of their stories—were they caught? Were they hanged? Did they succeed at running away and live a happy, fulfilling life somewhere else? I wondered what the best way was to dignify their lives and their suffering.

Why is the project called Tolerably Black? There was an ad for someone named Alfred that struck me for a couple of reasons. One was that it only offers five dollars for him, ten dollars if he’s found further away. Then it gets into his physical description: “ . . . about 5 feet high, tolerably black.” “Tolerably black” stopped me in my tracks. What the hell does that mean? We know that this is a physical description—maybe this is just the best way a Caucasian person in 1844 can convey before photography what Alfred looked like. We might never know what “tolerably black” meant in 1844. But I know what “tolerably black” might mean today, in 2019. So I named the whole show that because of the questioning of our identities as people of color in the United States. What are the boundaries? At what point have we crossed over into where we aren’t “tolerably” black anymore— when we’re uncomfortably black? Do you know what I mean?

I think so, but can you explain? I believe what they’re implying here is that the darker your skin, the more offensive you were. That thinking has driven how we as people of color view ourselves, how people who are not of color view us, and from there, which opportunities have been afforded to us and which have been denied.

Those two words—tolerably black— seemed like the most important thing. When a black person reads the term they might have a certain thought; people who are not black will have a different one. Those thoughts are the things that we have to talk about, because this “tolerably blackness” is why we often are on different sides of an issue.

Related: Racism Is a Heart Disease

My Buddhist practice is about unity; it’s about coming together and not differentiating ourselves, about really understanding that we are all human beings, pursuing happiness. So in my view, the more we can share and talk about our feelings about why we believe we’re different, the better for everyone.

What kind of reactions have you been getting from the people who participate in the installation? Pretty much every reaction that you can imagine. A lot of the time people are afraid, and that manifests itself as fear but also as anger. And if you’re carrying around something shameful and something about my work ignites that, then you’re not going to receive it positively. That’s my understanding, and it occurs on both sides. For example, there were two women of color who came to an event at Brown University. They had a really big problem with the nooses. One shared that two of her ancestors were lynched, and she said to this day her family still won’t talk about it. And the other woman’s family had become sharecroppers after slavery; they still live on that same land. She thought the work was traumatizing. As much as she was uncomfortable, I was like, “Right on.” I want people to feel uncomfortable. Otherwise I’d be painting tulips, you know?

It’s an uncomfortable conversation for a lot of people, I’m sure. How do you navigate such fraught dialogue? The two women I mentioned who were so resistant—I felt for them. I could see they were trembling while they were talking to me. And I said, “That’s why we’re doing this.” Because if your family can’t talk about these things, you can bring it here; this is a safe space for it. By the end, those same two women didn’t want the event to end! The catering people came and cleaned up, and we were still there talking.

There’s a shame attached to all these stories that hinders people from sharing them. I want to do away with all the shame. I want everyone to feel proud. I want people of color to feel like we can wear our history like a badge of honor. I’m the descendant of slaves, which means that there were some resilient people in my lineage that made some very difficult choices so that I could be here today.

You also actively participate in the installation by dressing up. Does it affect you? There’s definitely an emotional toll to it. There’s a video we play in the installation that shows me and a friend running away. That day in the park, it took us five hours to shoot what was reduced to ten minutes of usable footage. It’s hot and buggy. I’m sweaty. The shoes and the hoop skirt are uncomfortable. And I’m thinking, what was it like for my great-great-great-great-grandmother when she left? You hear rustling in the grass, and you start to think about how everyone these slaves encountered could have been the person who resulted in your demise. And not only that, but they were running into the unknown. It’s not like there was Google Maps. You were just relying on the kindness of strangers and I don’t know what else.

It sounds like it really connects you with your fourth great-grandmother. I grew up with a girl whose dad had passed away when she was young. She shared with me that when he would take her to the park, there was one intersection where they would stop and wait to cross the street. When he passed away, going to the park together was one of the things that she missed the most. She said she would go, even until she was a teenager, to that intersection, and stand in the place where he stood, because it made her feel really close to him.

I feel like that’s the only analogy I have. I mean, clearly, I did not have a physical connection with my ancestors as she did with her dad. But there is this becoming them that happens when I dress up.

What is your perspective on freedom for people of color in the United States today? Has it been found? I think it can change from minute to minute. I would like to believe that life is a million times better. I mean, I can make my own choices now, right? But I do also feel that when you make choices that aren’t successful, as a person of color you’re judged more harshly. And it can also be more difficult for you to get yourself back on track. There’s the Christian expression “There but for the grace of God go I.” It’s not to say that it’s hopeless. I believe in hope and I believe that you can turn any situation around. But society isn’t super forgiving if you are a person of color.

Related: What the Buddha Taught Us About Race

You mentioned that your whole family converted to Buddhism at once. Of course, I have to ask about how that happened. Yes, when I was 8 or 9. It started with my uncle on my mom’s side. He encountered a practitioner of shakubuku, the word we use when someone shares the practice with you. I think he was trying to ask her out on a date, and she said, “I’ll go out with you, but you’ve got to come to this Buddhist meeting with me first.” He went and said he heard some things that were amazing that he shared with his four sisters. So, adding up them and their kids and so on, it comes to about 20 people.

Do you see any other connections between your Buddhist practice and this work? Regular discussion meetings are a part of SGI, so I’m very used to communicating with people from all walks of life. I grew up with all kinds of people coming to my house and chanting and so on. It’s something that I bring to the project: the idea that no matter what color you are, you can be a friend.

There is also an immense respect for history and legacy in our Buddhist practice. We are constantly studying and sharing a lot about the three founding presidents and what they endured. I don’t see persecution as a hindrance. I think that’s what might be the biggest disconnect for people when they look at the project. Like, “This is horrible. How could you show this to us and make us look at it?” Whereas in our Buddhist practice it’s that you go through things that are difficult to endure, and that’s the winning, sometimes. There is a feeling of perseverance, to keep pushing forward. “Never give up” is one of our mantras. I think that would be the one connection that I see, not only in the way that I’ve had to never give up in terms of presenting my work, but also the fact that my ancestors didn’t give up, either.

—Photographs by Michael Avedon