The New York Times has called Anne Waldman that “combination of oracle, siren and den mother . . . at once deadpan and ferocious.” An explorer of poetry, she has written forty books and pamphlets in almost as many years. Her recently released Vow to Poetry (Coffee House Press) is a mix of autobiography, manifesto, poetry, and essays on poetics, Buddhism, politics, and more. Cofounder, with Allen Ginsberg, of Naropa University’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, Waldman divides her time between teaching, writing, performing and traveling. Writer Sonya Lea Ralph had a chance to speak with her last summer in Seattle.

You suggest your writing students take on the mantra “I exist to write,” to become attuned to the “delicate and fierce nuances of language.” How has this “writer’s mind” influenced your life?

I take the writing of poetry and the written articulation of a personal poetics—including its attendant vocalization or performance—to be a way of refining mind. As such it helps with “right view” in the dharmic sense. If one can be cognizant and sensitive to the “delicate and fierce nuances of language,” one may take on just about anything. Look at the trouble language gets us into! Observe its debasement, its doublespeak, its cruelty. Remember how the U.S. government didn’t understand or intuit how to apologize properly to the Chinese people when their pilot was downed? It’s about one’s attitude, perspective, one’s need for “negative capability,” balance, humor. The mind that concentrates on how language works, and how increments of sound and meaning and intellect may be made into something exciting and revelatory, may stay focused in other ways. It is a trained mind. Also, you might copyright a poem, but you don’t own it, you can’t monopolize language. You are just the vehicle. The practice of poetry is a form of “skillful means” or upaya in the Buddhist sense. But depending on one’s bent one might substitute a lot of things in the mantra: “I exist to make music,” “I exist to find a cure for AIDS,” and so on.

So what’s your sense of your role in a culture in which language is used as tactic, as in portraying oneself as a compassionate conservative without ever having to demonstrate one’s compassion?

My role is to be a language guardian. I uphold and query the use and abuse of the gorgeous, subtle, mellifluous, energetic and imaginative Mother Tongue! I think one of the downsides of the “New Age” has been its horrific debasement of language—and adjacently, its dangerous lack of intellectual discourse. The buzzwords around spirituality sound vapid and empty at this point. The Buddha would be horrified, I’m sure. It’s as if we all “know” what we’re saying so why bother to really be creative and articulate and express originality of mind? Gertrude Stein seems more Buddhist in her understanding of the “continuous present” and her use of participial phrasings to demonstrate the actual thinking, which in fact is veritable meditation in action. Wallace Stevens grasps Buddha-mind in his poem “The Snow Man”: “For the listener, who listens in the snow, / And, nothing himself, beholds/ Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.” Buddhism is not just a clichéd haiku with a flower and a quaint frog in it. Of course it’s another thing to really give the sense of the life of a real flower—what kind, specifically? Or what manner of amphibian? Minute particulars. “Look to the little ones,” Blake says.

I get nervous around self-enclosed solipsistic realms, where everyone is supposed to “get” it and is really brainwashed and not thinking on his or her own two feet. Or is not demonstrating originality of thought or language. There have been grand Buddhist teachers or thinkers who were also poets: Dogen, Milarepa, Basho. The way they’ve worked with the heaven, earth, and man principle through the haiku, and the dharmic discourse of a Tibetan doha, which is a celebratory songlike piece, for example. I certainly appreciate the need to examine the cultural patriarchal hegemonies of the power constructs of language and experience. The reexamination of the “canon” and the “nuclear family” and the food we eat and of course the “whole-earth” approach is refreshing and sound and necessary and overlaps with environmental awareness, but the emphasis on how everybody is feeling goes too far into the realm of spiritual materialism for my taste. It’s dilatory and self-deceptive.

If you don’t valorize reading and study and thinking and imagination, you are in trouble as a culture. You remain cut off from other cultures, other realities. It’s like the U.S. ambassadors who garner appointments because they made big campaign donations or because they like to trek in Nepal, but they don’t know a thing about the country they are working in, let alone the language. It’s really very sad and contributes to the criticism of the USA for its arrogant, isolationist policies.

So it’s much more than the hypocritical “compassionate conservatism” we need to guard against. It’s also the touchy-feely soft realm of lazy and disempowered speech: stale dead lingo that deadens our sensibilities, shuts down our sense perceptions. Words are powerful. William Burroughs calls the word a “killer virus.” It’s the ignorant folk like us—presumably on the other side—the bleeding heart liberal “enlightened” side—who should demonstrate language’s intelligence, humanity, and compassion by not allowing it to become canned, programmatic, pre-fab, disingenuous, ideological.

Your recently released Vow to Poetry includes essays and manifestos on poetics, Buddhism, and activism. In one of the articles, “Kali Yuga Poetics,” you proclaim: “Now more than ever the poem is a call to responsibility and action. To witness, grieve and alleviate suffering.” How might the experience of poetry lead us to activism?

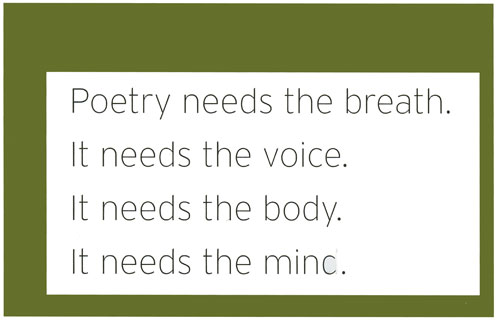

Poetry needs the breath. It needs the voice. It needs the body. It needs the mind. It needs to be able to dream. To imagine. Thus poetry depends on and recognizes the preciousness of our existence in the service of this particular art and of course in the service of so much more. It is rooted in the palpability of our existence and the inter-dependence, the pratitya-samutpada, of all of existence. And the poem wants to sing out, to communicate, to wake you up. The maker of the song who has this urge, this gift, sees how others are faring on the planet, including other writers incarcerated for their beliefs, who scratch their poems on prison walls, smuggle them out in samizdat publications and so on. Think of the great Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, whose first husband was executed, whose son was imprisoned under Stalin. She wrote Requiem for all women whose sons were in the Gulag. I am not talking about an easy, therapeutic confessional poetry that just talks about how you, the personal “I,” feels. Or suffers. It’s of a higher order and command. So there’s a way—through Shakespeare, Blake, Emily Dickinson, through poetries and cosmologies of cultures all over the world—that great poetry can inspire you to care for the planet, and for all its creatures and greenery.

Poetry has always been a radical presence in my life. I sometimes think it has saved my life. Its dark beauty. You know Emily Dickinson’s line “My wheel is in the dark”? And it’s not just about content. It rides you in so many other ways. You could say that the poetry of this last century and the current “dark ages,” where we are dominated by the lords and ladies of materialism, is in many ways a poetry of loss, impermanence, grief. “Can we make art after Auschwitz?” is the famous Theodor Adorno question. Yes, we must, I believe. It’s an imperative to articulate our humanity in this way. Poetry is still available to us, even as we move into stranger technologies and stranger modes of living. One needs a mind for it but it doesn’t cost anything, doesn’t require any gadgetry. In that way it’s also like spiritual practice.

What kind of activism has Buddhism led you to?

Buddhism has helped me appreciate others in a more profound way, in that one sees that everyone is suffering, everyone has a broken heart. Every face, as in Blake’s line, shows “marks of weakness, marks of woe.” Everyone is just a hairy bag of water, a poor klesha-ridden confused being. Even when they are arrogant and completely wrongheaded (in my humble opinion) and evil and barbaric, you can’t give up on them! Everyone wants to be loved, appreciated; everyone craves some kind of personal power. Everyone craves a decent life. But the power has to be debrutalized. Activism is part of Buddhist mind. The Bodhisattva Vow is Activism 101! You work to alleviate the suffering of other human beings, right? Isn’t that the point? Obviously you need to get your own trip together first, and there’s the rub. We have this precious human birth and freedom, and yet with so many of us who are privileged in this way, there seems to be an incapacity to get beyond our minor aches and pains. Gary Snyder has spoken of how our whole continent is haunted by the ghosts of decimated peoples, particularly the indigenous Native Americans and extinct animals.

Building and sustaining community and providing safe zones—primarily artistic and literary—has been the main thrust of the activism in my life. And traveling all over the planet to teach, perform, help poetry communities get started. Activity that often extends to modes of protest and demonstration and letter-writing campaigns and vocalizations of all kinds to protect these zones and by extension the whole metaphorical neighborhood! Last January 20—Inauguration Day—I went to D.C. with a group of poets to protest the “selection” of George W. Bush. We were there in solidarity with many African American citizens who had been disenfranchised in Florida and elsewhere, such as Cook County, Illinois, where 120,000 votes went uncounted.

I would say it is a spiritual practice to make sure everyone in America is granted the right to vote.

I’m thinking about the brutality that occurred in Genoa at the G8 summit, where many protestors were injured by the police, and which remained largely unreported in the corporate media. What do you think a Buddhist response to these acts of violence might be? How might we alleviate suffering at future protests?

I think both meditators and mediators should organize to form support teams for these civic demonstrations post haste, protests which will only be continuing more vigorously in the next years, as the struggle for the environment and the dignity of all living beings continues and more and more of our humanity is at stake. There should be a volunteer group of well-trained sane Buddhist practitioners with various social skills, working around the clock at the United Nations and ready to intervene at a moment’s notice anywhere on the troubled planet! Not to sound apocalyptic, but Buddhism predicts the coming Dark Ages, the Kali Yuga, and the ascendancy of the so-called Barbarians. We can parse that in any number of ways: cruel thugs, greedy warmongers, the fossil fuel guzzlers, fanatical nationalists, seemingly harmless yet divisive media pundits and so on. The Barbarians (or a better word might be the environmental jab fun hogs?’) are already here.

The Buddhist communities I’ve encountered in general—if I may say so—are perplexingly schizophrenic about how and when to act, as if there is some strange anathema attached to the ‘political’ realm. Is it too risky? Too messy? Or trippy? Or ego-prone? Wake up, dharma brothers and sisters! You can do both. Practice AND practice. I think if there are any survivors, down the line they will look back on this time as a second holocaust of incredible magnitude. A holocaust that decimated much of the planet and its denizens. Like the people who were in cahoots with the Nazis, who just stood by, the accomplices and collaborators, as we will seem, will be called to account.

Many of the teachers I know, including Bernie Glassman, Gelek Rinpoche, and John Daido Loori, are some of the most politically socially informed and astute people I know. Maybe there is momentum building within various Buddhist communities that I am not yet aware of. It seems to me that they need to unite to really be effective. There continues to be a strong activist strain at Naropa, engendered perhaps by the “outrider” strain of the poetics school and the example of Allen Ginsberg, in particular, and the urgent call for more diversity around issues of race, gender, sexual difference.

Author and healer Deena Metzger talks a great deal about our culture trivializing beauty. Metzger says, “I see the artist—the real artist—as carrying the sacred vocation for the sake of the community. You do the best that you can so that it is beautiful enough for spirit. So that it is beautiful enough to reveal what the community needs.” What’s your idea of the artist as carrying the sacred vocation on behalf of community?

It is very much your own individual responsibility to create and nurture beauty, and to carry along the community in all your acts of generosity in the creative work you do. It is an obligation to care for environment in that endeavor. You want a place where the deer and the antelope still roam. You want your poetry to contain only dead postmodernist references to television? You want a place that is hospitable to everything that lives. Clean air, clean water, decent affordable housing, and so on. How can one really in all conscience condone willful tolerance of arsenic in water? I mean, you have to be cruel and insane. Or talk about taking out pristine wilderness areas for the sake of a few buckets of oil.

Or conjure the inhumane conditions in a lot of the prisons in this nation…or the execution of the mentally retarded on death row. The Star Wars [defense initiative] presents a very scary scenario, and the weaponization of space is upon us…Breathe out. Tonglen—the sending and receiving practice where you visualize and breathe in negativity and breathe out its efficacy toward some harmony, peace, clarification—is one of the most brilliant of spiritual practices in that it works with our basic makeup: the breath, and the impulse toward being kind to others.

Which is why you “dedicate the merit” in any act of ordinary physical, mental nourishment. We all do these kinds of things: eating, sleeping, reading a book to a child, rescuing a wounded baby crow, standing at the top of the Continental Divide feeling the enormity of glacial energy, making love, reading Borges, Sappho, King Lear. I dedicate the merit of the revelatory dream I had last night, of the poem I just wrote, of the letter encouraging fair treatment and release for Leonard Peltier. So in dedicating the merit, you already have a community at hand. And it’s an invitation to shift your own thinking away from your own self. Community is always there from this point of view. And without being heavy-handed about it, you can at least try to be a good citizen in your immediate neighborhood and let it ripple out from there.

One of the sweetest stories from Vow to Poetry is “Last Days, Hours,” which begins: ‘You’d better come over,’ Allen Ginsberg says, voice steady on the other end of the line.” What was your greatest transmission from him in that time together?

“Generosity is the transcendent friend” is the line from the Zen oryoki meal-chants that conjures the energy and purposefulness of the life and times of Allen Ginsberg. I guess the transmission when he was dying was that there’s so much more work to do. He was generously bestowing the ongoing assignments. Shifting the load, perhaps. Take care of this, guard that, make sure so-and-so has a job and a place to sleep. Take care of the family and extended family.

What do you want the rest of your life to be about?

“Proud, open-eyed and laughing toward the grave.” That’s William Butler Yeats. More of the same, I hope. I love my life. I want to stay healthy, of course . . . but I also foresee a lot of struggle on the horizon. The environmental front is the most crucial, but that includes just about everything. It subsumes everything else you could even remotely fret about. Naropa still seems the best base of operations. Possibly there will be more contemplative-inspired centers, especially in the writing worlds. I’ll have to stay on the case of preserving, guarding the temporary autonomous zones of sanity and creativity, and help build new ones as well. I want to keep performing and collaborating with other artists, musicians. More books to write, several anthologies in the works, a new CD with help from my son Ambrose Bye, who is a young musician. We need to save the twenty-seven years of brilliant poetic oral transmission from the Jack Kerouac School, an effort we are calling the Naropa University Audio Archive Preservation and Access Project. Oh yes, and last but not least—a protracted meditative retreat, if I can keep still for more than a few minutes.

A Book of Events

In Milarepa’s Cave

Sit

the logs….

flogging is many lives come together

you will be good, you think

hunger is what you’ll never show pick this nettle

light a fire

your broth is the broth of kings

green is the mouth of the cloth-clad lord

sing your sacred songs—again, again

In Her Lament

spin

spin

the saint is a woman scorned wash your hair

your skirts

scent your hands with myrrh

say you will never die of love

spin

spin

Home

Circumambulate the house

Make first imprints on the snow

Fix what needs your hand

A wasp won’t perish

Let her live

—Anne Waldman

From Fast Speaking Woman by Anne Waldman, City Lights Books, San Francisco, 1996. New Expanded Edition. Used by permission of the author.