The Flower Ornament Scripture (Sanskrit, Avatamsaka Sutra; Chinese, Huayan Jing) is one of the most influential of all Buddhist classic texts. Early Mahayana lore in Central and East Asia held that this sutra was the first teaching of the Buddha immediately following his awakening, and that because of its exalted origin, very few at the time could grasp its full meaning. Over the centuries, the Avatamsaka came to be considered one of the most profound of all Mahayana texts. In the 20th century, D. T. Suzuki, widely considered the most influential figure in the introduction of Zen Buddhism to the West, remarked that “Huayan [the school of thought based on the sutra] is the philosophy of Zen and Zen is the practice of Huayan.”

For many years, the Los Angeles–based artist Tom Wudl has been meditating on theAvatamsaka Sutra, slowly and carefully producing drawings and paintings inspired by it. Grounded in a daily meditative discipline that includes both silent meditation and contemplation of images in the sutra, Wudl’s art probes the depths of Buddhist visionary experience.

One of the primary themes in the Avatamsaka is the ultimate interdependence and interpenetration of all things. This theme appears in the sutra itself and in later commentaries as “the jeweled net of Indra,” a visual image of a net strewn through space with sparkling, multifaceted jewels hanging from each of its countless interstices. Because of the interreflection among jewels, the appearance of each jewel depends on the appearance of other jewels, just as all things in the world reflect the influence of other things. The implication of this is that each jewel—each object in the universe—“contains” the entire cosmos within it.

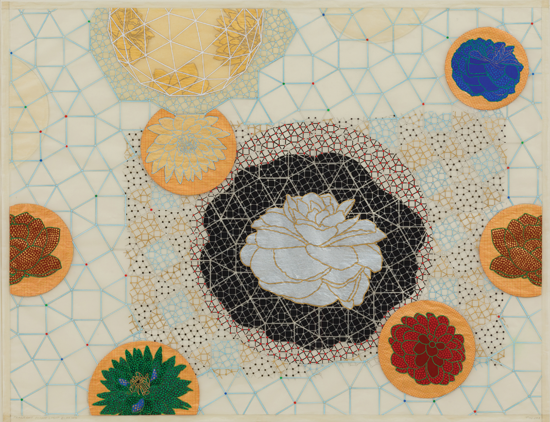

The net linking all jewels together brings the complex interconnection between all things into visual display. In many of Wudl’s paintings, this net provides the background skein that ties all images in the work together into a cosmic totality. In Fragrant Flame Light Blazing, for example, the larger woven network appears in the background while finer and more tightly interwoven nets surround each flower, telescoping up so closely that you can sense what the sutra means by juxtaposing “fragrance” and “light.”

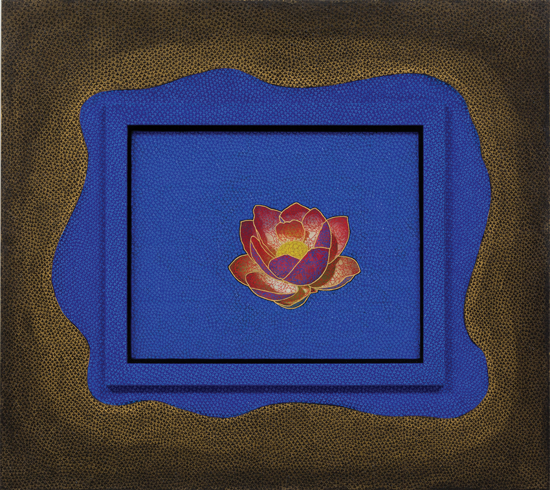

Flowers and jewels are the sutra’s images of perfection; they symbolize the mental depth and expansiveness of buddhas and bodhisattvas, those serene and deeply conscious beings in whom the magnificence and utter beauty of the totality come fully into awareness. The sutra describes flowers composed of gems, flowers that exude miraculous fragrances, flowers that emit heavenly music, and flowers whose color takes ecstatic possession of anyone whose gaze happens upon them.

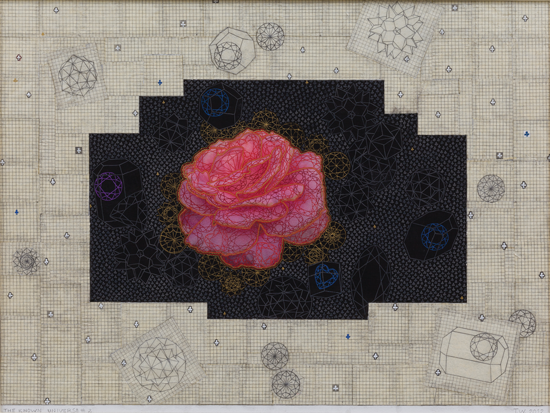

The innumerable flowers that appear in the sutra are a focal point of Wudl’s meditative art. Looking closely at The Known Universe, you can see that gemstones constitute the inner structure of the flowers, while in Unattached, Unbound, Liberated Kindness, the largest rose in the painting opens up into the caverns, or “mines of jewels,” that the sutra describes. In each flower we contemplate the Buddha’s transcendent mind of awakening. The paintings’s geometric shapes of net and cut gems fuse with the soft, rich surfaces of the flowers in a way that foils our inflexible expectations. The organic and inorganic interpenetrate.

The Avatamsaka Sutra is a compendium of numerous Mahayana sacred texts that circulated independently in northern India, Central Asia, and China until they were collected into one massive text probably in the 3rd or 4th century CE. Early portions of the sutra and then the scripture as a whole had an enormous impact on the shape of Chinese Buddhism, inspiring in the 7th and 8th centuries the formation of the Huayan school, which would become one of the two most important traditions of East Asian Buddhist philosophy. Similarly, the sutra was readily absorbed into the forms of Mahayana Buddhism that developed throughout Central Asia from Tibet to Mongolia.

The teachings of the sutra encompass virtually all of the most important Mahayana ideas and practices, but more than any other sutra it develops the concept and imagery of infinite interdependence, a worldview in which relations and movements undermine our mental grasping for stable, separate things. Seen at a level of sufficient profundity, it claims, even a simple flower contains the cosmos in its entirety, and from beginning to end this vast scripture aims to awaken in the reader a deep sense of how that seemingly absurd statement in fact describes the true nature of our world.

Reading the Avatamsaka is an exercise in meditation. The sutra guides the reader through shifting perspectives from one visual metaphor to another. This is what makes the sutra so difficult for us to read. It puts very little emphasis on story or narrative, in order to concentrate the reader’s attention on visualizing the world in a new way. The sutra aspires to evoke for the reader the depth dimension of the world in which we dwell and to teach us how to live insightfully in such a world—the world as it appears to the Buddha, where all things are integrated into a universal network of interdependence.

This cosmic vision and the meditative practices that generate it now inspire Tom Wudl’s artistic practice. Each painting demands uncompromising concentration from the artist. Repetitious detail and patient, delicate brushwork draw us as viewers toward that same state of focused absorption. One work—Unattached, Unbound, Liberated Kindness—took four years to complete. Internalizing the sutra’s teaching of the inexhaustibility of any single object in the universe, the artist probes into the depth and interior plurality of each flower so that we may glimpse the intricate complexity of its inner composition.

Tom Wudl’s paintings and the sutra that inspired them guide us in visualizing a world through the eyes of the buddhas and challenge us to consider the possibility that, in truth, this is our world.

A Translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra

Strewn about are flowers of beautiful mines of jewels,

Resting in the sky through the power of ancient vows.

Over an ocean of various adornments, stable and strong,

Clouds of light spread, filling the ten directions.In all the jewels are clouds of enlightening beings;

Traveling to all quarters, blazing with light;

Rimmed with glowing flames, beautiful flower ornaments

Circulate throughout the universe, reaching everywhere.From all the jewels emanate pure light

Which totally illumines the ocean of all beings;

Pervading all lands in ten directions.

It frees them from pain and turns them to enlightenment.The Buddhas in the jewels are equal in number to all beings;

From their hair pores they emanate phantom forms:

Celestial beings, world rulers, and so on,

Including forms of all beings as well as Buddhas.