If anyone will be remembered as a major ancestor of Zen in America, it will be John Daido Loori Roshi, who died on October 9, 2009, of lung cancer. Born in Jersey City, in 1931, into a working-class Catholic family, he was by nature a freethinker and a rebel. Dissatisfied with the answers provided by conventional religion, he considered himself an atheist in his youth. He used a fake I.D. to join the Navy while still underage, serving from 1947 to 1952. He later worked as a chemist, leaving that profession after seventeen years to pursue a lifelong interest in photography and a renewed interest in spiritual practice, brought about largely through the influence of the photographer Minor White, whom he met in 1971. White’s use of meditation and mindfulness techniques in his photography played a large part in Daido Roshi’s fascination with art as spiritual practice.

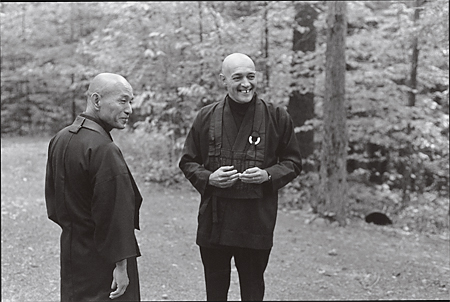

It was a natural progression for Daido Roshi to pursue formal Zen training with Soen Nakagawa Roshi, a master of calligraphy and haiku. But in 1976, he met Taizan Maezumi Roshi at Naropa University (then Naropa Institute), where Daido Roshi was teaching a workshop in mindful photography. The two men made an immediate and deep connection, and Daido Roshi moved with his family to Maezumi’s Zen Center of Los Angeles, where he headed ZCLA’s publications department and collaborated with Maezumi Roshi on a translation of Dogen’s “Genjokoan,” featuring Daido Roshi’s photographs.

Although Daido Roshi first regarded himself as a staunch layperson and had little taste for certain of the ceremonial and authoritarian aspects of practice (he famously threw back at Maezumi Roshi the first list of koans he received from him, declaring, “I’m not going to do these!”), he later moved in the direction of what he described as “radical conservatism,” a move he saw as necessary for authentic Zen practice to take root in America. He later ordained as a Zen priest and eventually received dharma transmission from Maezumi Roshi, becoming a lineage holder in both the Soto and Rinzai schools of Zen Buddhism.

In 1980, while visiting a friend near Woodstock, New York, Daido Roshi heard that a former Christian monastery—more recently a summer camp—was up for sale. Undaunted by the fact that the place had no heating and that he had to wade through several feet of water flooding the lower hall—not to mention the fact that he’d taken a monastic vow of poverty and was virtually penniless—Daido Roshi agreed, on the strength of a handshake, to purchase the building and 230 wooded acres on Tremper Mountain. The seller’s one condition was that the large wooden Christ figure that dominated one outer wall of the building should always remain—as it has, facing appropriately east, with arms spread wide.

Maezumi Roshi helped with a down payment, but the rest was up to Daido Roshi. By his own account, the place was saved from foreclosure at one point by a would-be resident who showed up at the eleventh hour, handing Daido Roshi her cash payment for an entire year’s residency up front. Winters without central heating were so cold that residents sat zazen [sitting meditation] swathed in blankets, emitting white clouds with every breath.

But despite his enormous efforts on behalf of the dharma, Daido Roshi would have shuddered at being presented as a saint. Having formed a close connection with him as his assistant at Naropa University, I spent nearly as much informal time with him as in formal settings, and noticed early on how completely at ease he was with simply being himself. If who he was at any given moment matched people’s expectations of what a Zen master should be, that was fine; if it didn’t, that was fine too. He had little patience for social obligations or ceremonial duties, except when he felt these involved an actual opportunity to present the living dharma.

Although Daido Roshi was one the great American masters of the Zen koan system and a deep scholar of the Zen classics, he was fond of using Western references to clarify points of practice. He’d quote from “Zorba the Greek” or “Alice in Wonderland,” or use Hans Christian Andersen’s story of the ugly duckling to illustrate the point that we are all buddhas, despite appearances. He loved to quote Walt Whitman; he felt the poet must have experienced a deep realization of his true nature to create work of such depth and clarity. My wife will always fondly recall how, just after we were married, he sang Italian love songs to us over lunch.

The man had range.

Here are a few words offered by Roshi’s students and friends.

—Sean Murphy

Sean Murphy’s latest novel, “The Time of New Weather,” was awarded First Place for Best Novel in the National Press Women Communications Awards.

It was an exciting time, when Maezumi Roshi’s first dharma successors were training together at Zen Center of Los Angeles. Tetsugen (Bernie Glassman) was developing Zen businesses, Dennis Genpo Merzel adapted EST Training for Zen, Joko Beck’s piano music drifted through the dark after zazen, and Daido produced Zen Center publications. I was the center’s physician. When Daido’s young son developed a headache, we thought it was a sinus infection, until he began watching TV with one eye shut. A brain scan showed a tumor in a location that made complete surgical removal impossible. Daido’s son was given a very small chance of surviving five years. Daido went to Maezumi Roshi, sobbing. Maezumi Roshi’s usual mode was grandmotherly kindness. In this case, a tiger emerged, attacking. How dare Daido collapse in self-pity! This was no time to give in to grief! He must rouse all his energy, think creatively, and do all he could to help his son! Daido emerged with new determination and strength. I put him in touch with doctors and therapists who practiced energetic healing, and while his son underwent surgery and treatments, Daido did energy work with him. His son is now a grown man and a father himself. Daido was always willing to learn and to do what worked. He told this story with great appreciation of Maezumi Roshi’s skillful ferocity.

—Jan Chozen Bays Roshi

I remember once seeing Daido Roshi come into the dining hall. He was casting about, looking for something. There was a young guy, maybe twenty-one years old—a new Zen student on his first residency. He asked shyly, “Roshi, is there something I can do for you?” Daido looked at him. “Yes,” he said. “Realize your true nature.” Then he went on about his business.

—Gerry Choko Reese, Mountains and Rivers Order senior lay practitioner

I connected with Daido in the 1990s in New York City. I knew little about the dharma. But I connected with zazen and the precepts, especially “Stop creating evil,” in which I recognized the trajectory of my life: I had come to practice in my mid-twenties after a nightmarish decade of drugs and alcohol. Daido learned I was one of those clean and sober people in the sangha, although still fairly young. In an early dokusan [teacher interview], he brought it up and then did the most unexpected thing—he gave a gassho [placing palms together at the heart] with a deep bow—and said, “Thank you for taking care of this at the start of your practice.” I was startled, because something I thought of with great embarrassment was being shown great respect. When practice later began to whittle away at my defensiveness, and my teacher began to appear fierce and demanding, I always knew that the person facing me held me with true love and respect, even if I didn’t feel it at that moment.

—Anonymous

I am in the monastery, teaching contemplative care of the dying. One monk has fainted during the program. Others are attentive and subdued. Old Christian ancestors seem present, even though the atmosphere is heartily Zen. It is fall, the leaves are red and gold. I join the gray-robed students who sit in straight lines for zazen.

I find the stampede to dokusan startling and equally startling, the voice of the monk admonishing those who are lax. I can sniff Japan and the Marine Corps, but I like the strength of the whole scene. This is Daido’s place, and it is plainly a reflection of his psyche, his heart.

A monk informs me that Daido has invited me to spend the evening with him and a few others at his house. I make my way to his modest home in the falling afternoon light, I find Daido and several others in front of a large TV, entranced by the hugely energetic dancing of Michael Flatley and his Irish Riverdance group. A moment of cognitive dissonance; then I find a seat on a broken-down couch and join in.

That night I enjoyed my friend’s utter and naked pleasure at things seemingly non-Zen. I was grateful that he did not drag meaning into our midst.

—Roshi Joan Halifax, founder of Upaya Zen Center, Prajna Mountain Buddhist Order

Once she had some questions—she was about seven—and he sat down with her for dokusan in the dining room. He took it seriously enough to call it that: dokusan. Eliza remembers her question as “What happens to us after we die?” She doesn’t recall Daido’s answer, but remembers she was satisfied at the time. Now she says she wishes she did remember, because she still has the same question. There’s a painting Daido gave Eliza, with a little girl and Daido sitting cross-legged and a tree with an owl in it saying “Who?” It says “Daido loves Eliza.” Daido really connected with kids.

—Wally Taiko Edge, Mountains and Rivers Order senior lay practitioner

An enduring image many have of Daido Roshi is of him riding his vintage red tractor as he cut grass in the large field adjacent to the monastery. For smaller swatches we used the Gravely, a lawn mower that I came to love while in residence. The Gravely was akin to an aircraft propeller facing down, and it generated enough power to propel its rider at a brisk clip. I moved quickly, smartly turning the powerful machine with precision—an intoxicating feeling.

It was spring, and I was approaching the front gate, where a magnolia tree stood in full bloom. I had a good head of steam and pulled a lever—the wrong one. The mower sliced through the magnolia’s trunk in an instant, leaving a tiny stump. Magnolia blossoms were everywhere.

I was appalled, but when Daidoshi arrived shortly thereafter, he simply surveyed the devastation, saying little. The next day he presented me with another magnolia to plant, near the stump, which is why there are two of them today; the original came back stronger than ever. During the ensuing months, I became Daido’s arborist. He had me planting trees all over the place.

—Donald Genshin Bucher, Mountains and Rivers Order lay practitioner

After my mother’s death, suddenly alone with Daido in dokusan, I doubled over in sobs. With the firm, comforting touch of a hand on my shoulder came a quiet voice of perfect understanding: “Now your practice is crying for your mother.”

—Steven Hozan Baker-Horvath, Mountains and Rivers Order lay practitioner

I’d finished a month at the monastery and was pondering staying for a year. I hadn’t a clue about practice or monastic etiquette. I’d moved from a ranch in Wyoming; the only time I felt comfortable in those early days at Zen Mountain Monastery was when I had a hammer or chain saw in my hand.

One night there was a windstorm that blew a bunch of pines into Long Pond. We got in Daido’s canoe (which made him very happy), and he steadied it while I cut logs with a chain saw, standing and balancing in the bow. I plowed through the wood, sometimes with just one foot in the boat and the other braced against a log. “You’re fucking crazy,” Daido said, smiling. I didn’t know Zen masters swore.

After I’d cut them, Daido got his beloved tractor and with a thick rope began pulling the trees from the pond. I’d tie them, he’d drag them out. With one heavy log he stalled the tractor and cursed, started again, and gunned it. The rope snapped like a bullwhip, missing my head by only a couple of feet, sounding like a shot from a deer rifle. Daido turned off the tractor and calmly said, “I guess we should stop.” There was a long silence. The air smelled of pine and pond. Daido stood watching me, a faint smile on his lips; something was happening between us, but my mind was blank.

“Two feet one way or the other and poof!” he explained.

I felt strangely at home. “You’re fucking crazy,” I told him, smiling.

I stayed the year.

—John Kain