Inspired, illuminated, she crouches on Lo-chia Island, a tiny dollop of land in the restless brown waters of the South China Sea. She hunkers down and springs above the waves, her white robes billowing, winglike, behind her, one strand of glistening black hair falling on her neck from her tightly wound bun, her eyes beaming forward at the green hills of Putuo Island. One foot strikes the shore with such force that it sinks into the rock, making a footprint. She is home.

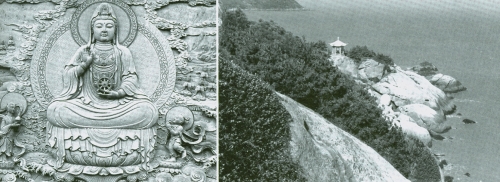

“She” is Kuan-yin, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Her home, where she has received her pilgrim guests since the tenth century, is also called Mount Potalaka (“holy mountain”) and Putuo Shan (shan meaning “mountain”). My traveling companion, Phyllis, and I arrive there not with Kuan-yin’s ecstatic leap but by a two-hour van ride from our Shanghai hotel to Lu-chao Harbor, then by boat to the island.

Several stories chronicle Kuan-yin’s arrival on Putuo Shan. One concerns a statue of her that was peacefully residing at Mount Wu Tai, a sacred mountain on the Chinese mainland. A Japanese monk named Egaku admired the statue so much that he “acquired” it and set off by sea for Japan with his treasure. But when his boat neared Putuo Island, the sea filled with iron lotus blossoms and the boat could not move forward. Frightened, Egaku prayed ardently to Kuan-yin, and the boat moved closer to Putuo’s shore, where a resident saw its predicament. He transformed his own home into a shrine and took the statue in. Once Kuan-yin was installed, the lotuses disappeared from the sea, and Egaku’s boat was released to sail back to Japan. The shrine became known as the “Temple of Kuan-yin Who Refuses to Leave.”

Though Phyllis’s parents were first- and second-generation Chinese immigrants, she grew up in a black neighborhood in Los Angeles and knows only a shred of Mandarin. We have undertaken this pilgrimage because of our shared fascination with the multifaceted deity who is the most beloved goddess in all of Asia. We plan to stay on the island: to meditate in the temples, perhaps to experience a vision of Kuan-yin, and to organize a retreat on Putuo for Americans. I also want to interview the nuns who live on the island, and have engaged a translator.

Kuan-yin has a curious history. As Chinese scholar Ch n-fang Y says, “Of all the great Buddhist deities, Kuan-yin alone underwent a sexual transformation.” When the Indian bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara was brought to China in the fifth century, the Chinese made him their own, but over several centuries, by associating miracles attributed to him with indigenous female life stories and images, they transformed him into the female Guan Shih Yin, or Kuan-yin.

Suddenly, putuo island, green and hilly, rises from the sea before us. After settling in at our hotel, we join the people who stroll in the sweltering twilight. We’re both inordinately excited and somewhat surprised to be here, where for the last thousand years pilgrims have come to receive Kuan-yin’s blessings and even catch a glimpse of her. I’ve come for a deeper identification with the quality of compassion embodied in Kuan-yin—for a softening, a connectedness to the sacred.

Phyllis and I wander the island, where cicadas thrum in the trees, creating an umbrella of sound. We feel Kuan-yin’s presence in the warm, strong wind. The streets of the little village are paved with cobblestones and lined with open-air restaurants where fish, eels, and crabs swim in plastic tubs a few feet from the tables where they will be eaten—a truly blasphemous feature of Kuan-yin’s island, for she requires that her followers adopt a wholly vegetarian diet. But Putuo receives over a million tourists a year, and the majority come to swim off the long pale-sand beaches and eat fresh fish, visiting a temple now and then for amusement.

On our first morning, we set out for the Temple of Kuan-yin Who Refuses to Leave and the nearby Cave of Tidal Sound. In the courtyard of the yellow stucco temple, we buy the bright orange cotton pilgrim bags with their lotus decoration and large black characters. People take these bags with them to each temple to collect souvenirs, and receive a red-ink stamp to show they have been there. A sincere pilgrim will be buried with her bag on her chest. Phyllis and I buy candles and incense and offer them in the glassed-in stalls set up for this purpose. Inside the shrine, we encounter a stunning white marble Kuan-yin statue seated in meditation, holding a willow twig in her right hand. We then descend steps to the stone banister that borders the Cave of Tidal Sound. It is not a real cave but a huge vertical gash in the cliff face. Surf pounds below. Tourists line the banister, peering down into the abyss. Many people throughout the centuries have reported seeing Kuan-yin here, and some of them have reputedly received dharma instruction from the apparition. One theory for the visions—put forth by a Westerner—is that at certain times of year, under certain barometric conditions, sunlight falls through a hole in the top of the cave and illuminates the spray and haze produced by the pounding surf below, making a bright veil through which Kuan-yin may choose to show herself—or, viewed differently, through which a pious pilgrim may imagine her presence.

Next to the banister stands the Finger Burning Stele, an upright stone engraved with text forbidding pilgrims to burn their fingers in order to invoke Kuan-yin. Centuries ago, a foreign monk did just that, lighting his fingers like candles and letting them burn down, as an offering to Kuan-yin. When all ten had been reduced to stubs, the bodhisattva appeared to preach the dharma to the monk, and gave him a precious seven-colored stone. After that, people got the idea of flinging themselves from the cliff into the cave to drown in the surf, committing themselves to Kuan-yin as they committed suicide.

We have traveled to an island whose earliest location is not in this world but in the realm of scripture. The Hua-yen-ching (or Flower Garland Sutra) chronicles the travels of the pilgrim Sudhana (Shan ts’ai), who after a long search finds Kuan-yin on Mount Potalaka. There, in a clearing in the woods, seated on a diamond boulder, she instructs him in the dharma. Another scripture, the Sutra of the Thousand-hand-and-Thousand-eyed Kuan-yin Great Compassionate-heart Dharani, is set on Mount Potalaka, where Kuan-yin hosts the Buddha and teaches the dharani (magical invocation) to an assembly of bodhisattvas. (The Mount Potalaka of the scriptures also gave its name to the ancestral home of Tibet’s Dalai Lama, the Potala Palace, because the Dalai Lama is believed to be a reincarnation of Avalokiteshvara, or Kuan-yin.)

Putuo has endured a long, often stormy history, beginning before its transformation, in the tenth century, into a major Buddhist pilgrimage site. For centuries the island harbored Taoists who went there to conduct alchemical experiments, and it was an important maritime trading port. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Japanese pirates and “red barbarians” (Dutch traders) periodically ravaged the island, pillaging the population and destroying temples. Putuo Shan’s history is also one of patronage, with influential people such as the Wan-li emperor and his mother building structures and encouraging practice; and of monks and pilgrims having visions, erecting shrines, inscribing rocks with their revelations. Thousands flocked here for the observance of Kuan-yin’s birthday and enlightenment, when they held all-night vigils. In 1929 there were 88 small cloisters and 128 hermitages under the direction of the monasteries. Until 1949, about two thousand monks and nuns lived on the island, except at pilgrimage times, when six to seven thousand additional monastics came. During the Cultural Revolution, many of the structures on Putuo Shan were further devastated by the Red Guards. Three large temple-monasteries now dominate the island, which is only eight and a half miles long and three and a half miles across.

As Phyllis and i walk the island, I have the feeling that we and this piece of land exist in parallel worlds: one the realm of the holy mountain floating between sea and sky, where Kuan-yin sits on a diamond throne, quietly speaking the dharma to Sudhana; the other this material Putuo of history and our own sensory experience of cliffs and muddy water, shrines and hotels noisy with tourists. As the days go on, the luminous world of Mount Potalaka begins to dim. I feel restless, disillusioned. Being with our translator, Helen, has brought home the secularization of Putuo Shan, and its dominant identity as a tourist spot. Helen’s rattling off of Buddhist history is just that—history, even while she recounts miracles and sacred visitations. Nowhere in the temples is it possible to sit and meditate, as the altars are roped off like museum exhibits.

At the Cave of the Brahma Voice, Phyllis and I sit on a bench looking out at the walls where visions are supposed to appear. Before us is a clutch of tourists eagerly scanning the rocks for a glimpse of the bodhisattva. A friendly old monk sits down with us. He points out the place on the cliff where Kuan-yin can be seen, and gives us each a medal. Although we stare at the rough wall, we see only rock.

Discouraged again, still I have hope for the nunnery, where we’ll go tomorrow and where I’ve heard the nuns are sincere in their spirituality. I’m hoping that they will share their chants with us and talk about their relationship with Kuan-yin Bodhisattva.

The next morning, we set off up the hill behind the hotel to the big rocks and the Meifu Nunnery. When we arrive, the nuns are conducting a service before eating. Mostly older nuns, with gray robes and shaved heads, they stand in an open chamber to chant. When they have finished, I try to talk with them, through Helen. They avoid my questions by saying, “I’m just a simple nun; I haven’t studied; I don’t know anything.” Helen explains that they are afraid of foreigners.

That night we eat watermelon for dinner in our room and then pay two yuan to go down a flight of steps to the beach. The sea wind cools a bit. The sky flames and then slowly darkens, revealing a canopy of bright stars that poke through in clusters. We sit without speaking on the damp sand.

But I have not given up the quest; I determine to pursue a stronger awareness of Kuan-yin, to uncover some sign from her that she is present.

In the early morning of our last day I go out to walk on the beach. I find a shelf of rock that is backed by bushes, so that when the sun rises high in the sky I will be shaded. I look up the beach to the Cave of Tidal Sound, the first place we visited on the island, then sit down cross-legged and begin to meditate. First I take refuge, then chant the Namo Guan Shih Yin Pusathat I have learned from a tape, then fall silent.

Cicadas buzz loudly in the bushes behind me; to my left, the surf murmurs. The breeze gently touches me, keeping me cool. Gradually I understand that each of these is the voice of Kuan-yin. And the rock, and the big brown bugs skittering about. And me, my own body/mind process sitting here. It’s all Guan Shih Yin. Which is what I already knew, didn’t I? And wouldn’t I have known that back in California? Yes, and no.

The few people down the beach keep their distance. I settle fully into the elements—ocean, rock, breeze, sun—knowing them to be Kuan-yin; that is to say: nothing, emptiness, suchness—spirit or truth so inherent in all the elements and their motion that it’s almost not worth remarking on. What a joke, then, to come here to find Kuan-yin, and to visualize her as a Chinese woman. I feel amused and at ease, and I stay sitting a long time.

Back in our room, I pull out an article by Chun-fang Yu, who writes of “the Ch’an tendency to dissolve place back to empty space. Indeed, from the enlightened perspective of shunyata—emptiness—Potalaka is nowhere as well as everywhere.” I think how that insight on the beach was not unlike my awareness, at home in my dim living room early one morning, when I suddenly knew that none of this “practice” was anything other than daily life. It was not exotic, not special, defying even the attempt to cordon it off into “meditation.” It could not be contained in a definition—it simply was. I find that awareness here in the hotel room: Kuan-yin in the tree outside in the courtyard; a bird chirping; flowing reflections of light from the surface of the pool outside up onto the beams of the hotel; this table cluttered with small red biscuit packages; my hand holding the pen and moving across the pale lavender sheet of the legal pad; Phyllis’s soft breathing from the bed against the wall; the ticking of an air vent; a boat whistle; my thoughts, anchoring me in the great web of consciousness that is China, the world; my body, comfortable for the moment, at ease, container for the thread of awareness that makes me human—all this is Kuan-yin, all this nothing, all this the sum of my experience.

Back in the United States, I periodically ask myself what meaning “the feminine divine” has for me, a twenty-first-century American woman. I know I will never apprehend Guan Shih Yin as a Chinese person does. But I also know that, just as Kuan-yin is bigger and more universal than Buddhism, she is also bigger than Chinese culture. She can leap across oceans just as she leapt from Lo-chia Island to Putuo Shan. She’s here in the United States, venerated by people of many cultural backgrounds. Her footprint is permanently engraved on America’s shore. And I have discovered that far from being a distraction—something “out there” to pray to—Kuan-yin, if approached wholeheartedly, always brings me back to the deepest, most universal part of my nature.

Historical information in this article thanks to Dr. Chiin-fang Yii.