. . . begin to welcome back / all you sent away, be a new annunciation, / make yourself a door through which / to be hospitable, even to the stranger in you.

—David Whyte, “Coleman’s Bed”

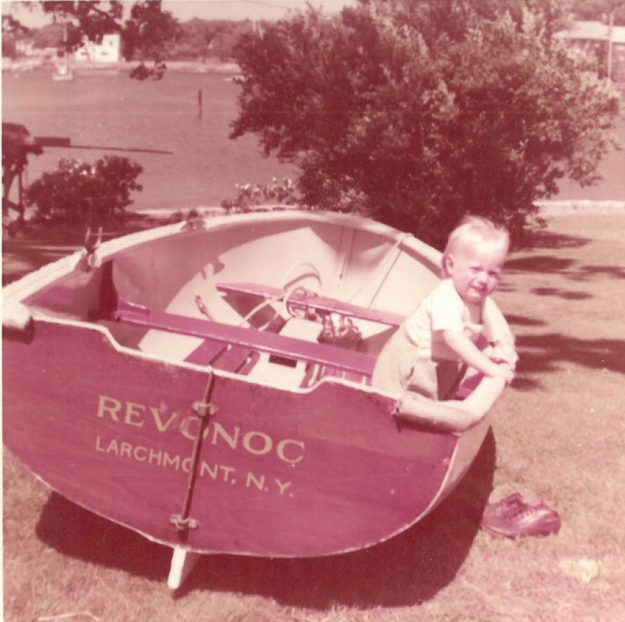

The heart of my family vanished on January 2, 1958, in a shipwreck—a fleeting event of upheaval whose fallout continues decades later. When there are no survivors and no meaningful recovery of wreckage, what’s left is only speculation. And the long legacy of unresolved grief. Not yet two, I was the youngest orphan of the downing of the Revonoc.

The gale blasting from the northeast on that day was the worst winter storm in the 47-year history of the Miami weather office, and no one had predicted its coming. At 8:30 that morning, a mild squall warning went out for the Miami area. Six hours later, a northeast wind sprang up, blowing out storefront windows and hammering boats with 70 mph gusts and 40-foot waves. Scores of commercial boats and ocean yachts were caught unaware, and many went missing. But by January 8, six days after the storm, all had been accounted for. All except for my family’s boat, the Revonoc.

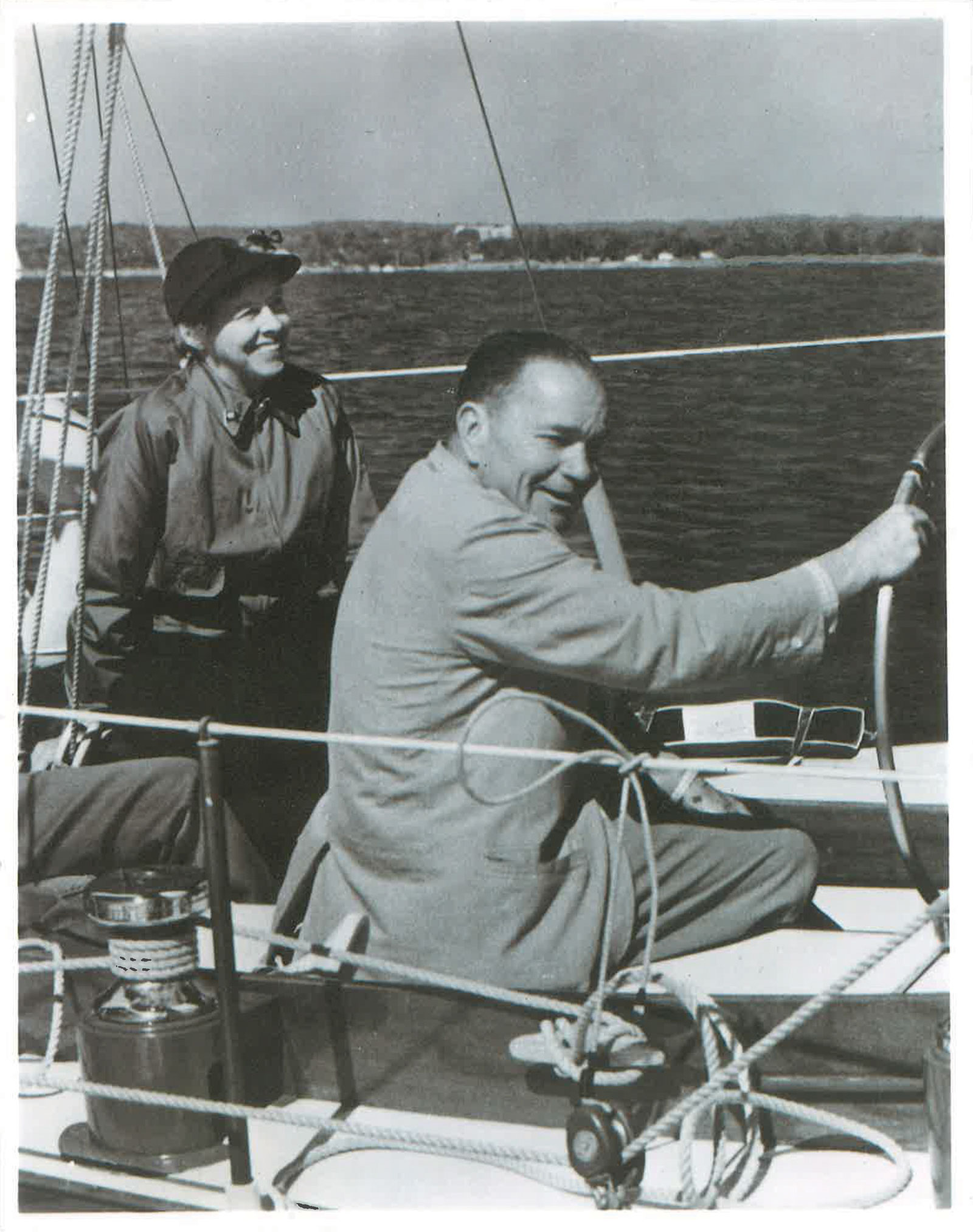

My grandfather, Harvey Conover, Sr., then 65, had been at the helm. One of the country’s most esteemed skippers, he had aboard his wife, my grandmother Dorothy, age 60; his son, my father, Larry, 26; my mother, Lori, also 26; and Bill Fluegelman, 29, a friend who had served in the US Coast Guard with my father. Since mid-December, my grandparents had taken a leisurely cruise through the waters of the West Indies and rendezvoused with my parents and their friend in the Florida Keys just before New Year’s. On Wednesday morning, January 1, they set out from Key West for Miami, where my grandfather had an appointment with a sailmaker on Saturday, January 4. The trip from Key West to Miami was just 110 miles, and the Revonoc should have easily made port by midday Friday. The storm struck on Thursday afternoon.

Since no one was expecting the Revonoc until Saturday, the day after the epic storm, Friday, January 3, wasn’t considered. A number of large boats caught in the gale had also not returned. The sea had yet to settle; all rescue efforts were delayed. When the Revonoc did not show up for the appointment on Saturday, Miami yacht broker Richard Bertram, a good friend of my grandfather’s, called the US Coast Guard. Radio dispatches went off to ships in the surrounding area in hopes of a sighting. Sunday arrived with no word from anyone. It was on the morning of this day, Sunday, January 5, three days after the gale, that the Coast Guard called to inform my Conover relatives that the Revonoc was officially missing. The remaining Conover children, my two aunts and uncle, were swept into a miasma of disbelief, panic, and impotence. They focused on the immediate urgency of finding the lost ship, speculating that our family could yet be clinging to wreckage, or washed up, injured and needy, on some distant island shore.

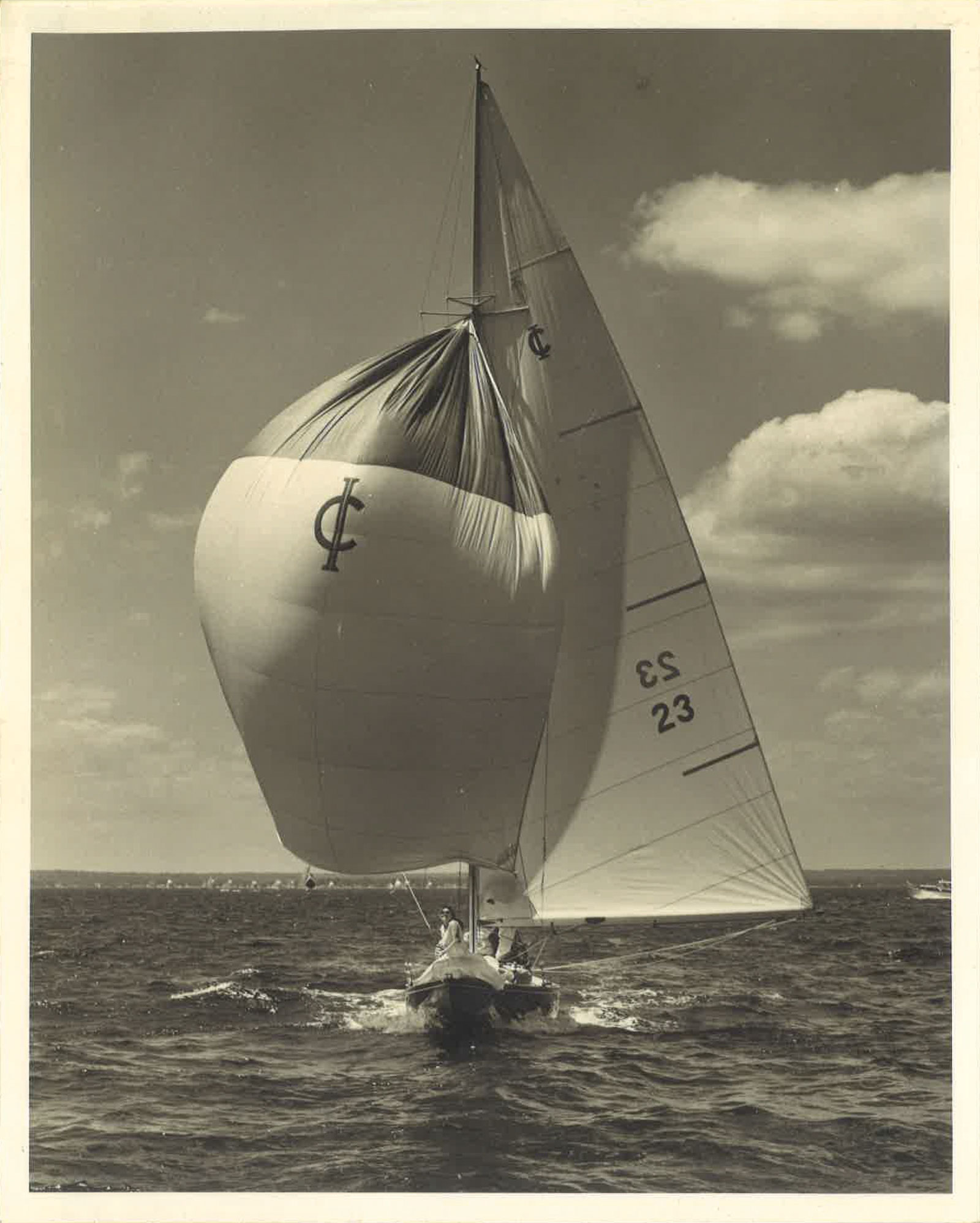

Publisher of Yachting magazine and a sailor for over 55 years, Harvey Conover, Sr., had, as competitive sailors say, “collected a lot of silverware.” Rated among the top dozen ocean-racing yachtsmen of his time, he named all his boats Revonoc—Conover spelled backwards—and with them he won 23 firsts, 14 seconds, and 6 thirds in major races ranging from Long Island Sound to the Bermuda Cup to the sometimes deadly Fastnet Race off the Irish coast. Everyone who knew my grandfather understood that he would neither give up nor fail.

Continuing stormy seas hampered official Coast Guard rescue efforts on Sunday and Monday, but on Tuesday, January 7, five days after the storm, one of the most intensive sea searches in American history was initiated, involving the US Coast Guard, the US Navy, the US Air Force, and the Cuban Navy. The New York Herald Tribune reported: “Fourteen Navy, Coast Guard and Air Force planes, five Coast Guard helicopters, a Navy blimp, the big Coast Guard cutter Sebago, three civilian planes, eight vessels of the Cuban Navy and two of their military aircraft combed the shores, reefs, islands and waters in all directions.” The rescue soon widened to encompass thousands of square miles. For months afterward, as the official and unofficial search parties scoured every last possibility, the Revonoc’s disappearance was followed by the nation in newspapers from The New York Times to the Fresno Bee, and was featured in magazines such as Sports Illustrated and Boat.

During those first days of desperation and disbelief, during the wait for the Revonoc and its crew to be found alive, my sister, Aileen, and I were taken in by a relative who lived nearby with three girls of her own. Soon, we would need a new home. My grandfather was a well-known businessman and yachtsman, and my father, too, was a national sailing champion. So confident were they of their expertise that my parents had left no plans in case of their deaths. Now, as the reality of the terrible drownings crept over the remaining kin, decisions had to be made. My childhood soon became embroiled in a vicious custody battle. My paternal aunt, my father’s sister, Fran Gagney, was given majority custody of us, but my sister and I were to spend every other weekend with my maternal grandmother, Mary. During the first decade of my life, my grandmother went to court three times with a small army of lawyers and psychiatrists to reverse that decision, but she never succeeded. However, behind the courtroom doors and within the walls of her home she waged a war, filling me with vitriolic stories about my paternal family. It left me feeling adrift, with no place to call home.

Over the subsequent decades, those of us left behind found ourselves unwittingly reenacting the loss, abandoning others as we had been abandoned, drowning through alcohol or drugs or within the bunkered dissociation of grief. All of us, child or adult, reacted to the disaster as orphans, exiling ourselves from our own suffering as well as from one another. We wanted what Keats, who lost his father at the age of 9, describes: The feel of not to feel it / When there is none to heal it. And so the Revonoc continued to haunt us, each person the accident’s unique heir, each life folded into its mangled trajectory over time, the immediate pain subsumed only to reemerge again and again unexpectedly, compounded and convoluted.

When I disclose that I lost my parents at 18 months, people inevitably, and with great relief, say: “Oh, then you couldn’t have really known them.” Research on early-childhood loss clearly contradicts this notion. The feral desolation that began to erupt in my forties without warning contradicts it. Though we may try, the howl of our deepest griefs cannot fit the confines of a narrative but inscribes itself in our bodies—even causing heritable changes in gene expression. As the poet Claudia Rankine writes in Citizen: An American Lyric, “The world is wrong. You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard.” Within every orphan there is a cellular memory of Before and After. Even if the adults say you were too young to remember. Even if you convinced yourself for decades along with them.

For years, I summarized the accident and its aftermath in careless shorthand. I’d been schooled in silence and numbing: no Conover ever spoke of the tragedy.

For years, I blithely summarized the accident and its aftermath in careless shorthand: My parents and grandparents drowned during a freak storm in the Bermuda Triangle. People would look to me for some clue as to how I felt but would find little in my affect to guide them. I’d been schooled in silence and numbing: no Conover ever spoke of the tragedy. The abrupt chaos in my family triggered an achingly slow unraveling of what had existed before, with relationships and loyalties frayed and snapped, lives and fortunes divided. None of my relatives could bear the shattering of all they’d cherished and believed in.

After January 2, 1958, as the days and months passed by, the reality of no survivors became indisputable. Many of the adults left behind could not accept the incontrovertible evidence. That the accident occurred in the Eastern Seaboard’s yachting culture, where cocktail hour was the daily vespers, further postponed their grief. In the cheerful clinking of ice cubes, in the fluid gold of a Manhattan, anguish could be smoothed over much as a wave retreats to the ocean and leaves the sand momentarily flawless.

My family is not alone in hiding behind this kind of response. As a student of the dharma over the last three decades, I’ve discovered more and more the relevance of my orphanhood to all of us. What I’ve seen: from the most intimate aspects of our self-awareness on the meditation cushion to our relationships in the wider world, we act as orphans more often than not, shunning painful experiences exactly as an orphan would. I am simply an amplified example of the many ways we each attempt to remove ourselves from our fundamental vulnerability.

At root, the taste of all suffering is separation. Dukkha, stress, begins at birth: form brought forth from formlessness, birth giving rise to a separate human embodiment. Some months after this, an infant realizes that Mother is her own distinct being, and his sense of safety and unity with her is shaken. As we grow up, our sense of individualism solidifies. We begin to see ourselves through the eyes of others; we are sure we are ourselves and no one else. The Buddha warned against clinging to this misconception of an independent, enduring self—the root of all suffering. Yet from infancy onward, from every corner of society, we are encouraged to magnify, curate, and improve upon this mask of separateness and to orphan ourselves from everything we are actually connected to.

Related: Noticing Space

And then there is the inner orphaning. Many hours on a meditation cushion have spotlighted the subtler psychologies of exiling myself from myself. Before I realize what’s happening, I’m driving away some unwanted emotion that arises, or judging my memories, ideas, and actions. I realize I’m relating to myself as an enemy, an object to be fixed into some ideal notion of who I should be. It’s apt that Ajahn Sumedho, a major figure in the Thai Forest tradition, calls the thoughts and feelings that we shame into the dark corners “orphans of consciousness.” I have many of them. So do we all.

Convinced that I could break free of the turmoil bequeathed to me, I fled my East Coast roots at 17, a wide-eyed seeker on a pilgrimage looking for a spiritual home to fill a chasm in me I could not name. Like the classic orphan figure of folklore, I set out on a quest. Perhaps peace would find me on a Colorado commune, or in the deserts of the Southwest, or walking the length of the Swiss Alps solo, or in a martial arts dojo in Japan, or skirting the heights of the Himalayas.

Hiking alone in Nepal during these years, I made my way along a thin path above a gorge and a foaming river far below. A Tibetan Buddhist monk walked toward me headed in the opposite direction. Even amid the drama of these peaks that kept me craning my neck to admire them above the clouds, his crimson robes startled me. He was also the first person I’d encountered in hours on this trail. I carried a large backpack, yet he bore nothing but a small bag slung over one shoulder. When we closed in on one another, he caught my gaze, smiled brightly and kept walking. I stopped to take in the moment. It struck me that perhaps I’d never seen a human being truly smile before. I’d never witnessed such unfettered joy and freedom. What did it take to be able to smile at a stranger like that? And at life? My compass toward the dharma was set.

After I had gained a BA in religious studies in Colorado, jobs pulled my husband and me to the Bay Area of California. We’d been looking for a spiritual home for our growing family and found ourselves living a few miles down the street from Spirit Rock, an Insight Meditation center in Marin County. I came home from my first meditation session there and told my husband, Doug: “I found what we’ve been looking for.” We both began a daily lifetime practice under the teachers there, which we continued when we moved to Washington State and formed a new sangha.

For decades I believed I could outpace my legacy through spirituality, mountaineering, therapy, marriage and parenting, through careers in media, social work, and education. I reclaimed my birth name and shed my adoptive moniker of Gagney so I could start anew. But grief is infinitely patient and never static. In time, I, too, sank into the Revonoc’s history. The arc of my life circled back to what it knew best: the habit of separation and orphanhood. When I reached middle age, my relationship with my sisters—already troubled—fractured; I found myself being abandoned by not a few dear friends and associates; and the relationship I had with my Spokane sangha of 20 years ruptured. In spite of my best efforts—all the psychological and spiritual tools accessible to a Baby Boomer—I hadn’t escaped. C. G. Jung said it this way: “The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate.” Forced by anguish into the sea where past, present, and future still churned, I finally turned to brave my family’s story, my story: sink or swim.

Forced by anguish into the sea where past, present, and future still churned, I finally turned to brave my family’s story, my story: sink or swim.

Orphan is not only a noun; it’s also a verb. We fence ourselves off from one another despite a primal instinct to belong. We also become experts at abandoning ourselves. When I breezed through the first page of my memoir-in-progress aloud to a group of writing companions—the page that recounts the simultaneous loss of my parents and grandparents—just as affectless as I had been for years with others, my friend Julia reached out and put a hand on my forearm.“Stop,”she said.“Please.” Mouth agape, eyes brimming with tears: “We must let this sink in.” Julia continued to weep. The other writers looked at her and then back at the pages I’d given them to comment upon. I was ready to move on and talk writing craft, but no one spoke. They all knew better. Julia had invited my grief to the table, and my ghosts were congregating around us. The group held me unmoving in that space, in that roaring, swallowing, sea of silence. We held our breaths and waited until I, too, at last began to cry.

I’d never cried about my family’s disappearance. I’d hardly ever labeled myself an orphan. Although I’d struggled with serious depression as an adult—like clockwork every January, the month when my parents went missing—it was within these few moments that I saw her. For a mercurial moment. For the first time. The trembling, fearful child who had waited for me. She was an orphan twice abandoned. First by the sea’s hand, and then, in not braving my pain, by my own. But now the group witnessed it. Now I knew. Now that orphan knew. We’d seen each other, and I could no longer walk away.

The dharma offers us hundreds of modalities to reverse the habit of experiencing ourselves as separate from the world and each other. Ajahn Sucitto of the Thai Forest tradition enjoins us to bring a sympathetic intimacy to all that arises in our field of experience. There are thousands of stories, suttas, and methods from every tradition that can affect this turn toward inclusivity, but we have to practice and know them well enough that they begin to saturate our awareness away from a default to aloneness. Frank Ostaseski, another well-known Buddhist teacher, gives us a short, positive directive: “Welcome everything; push away nothing.”

I have found that embodied awareness is my greatest truth-teller and my ever-present touchstone of solace. Compared with the mind’s speed and lightning squalls of emotions, the body’s energy field is relatively steady, tangible, and uncomplicated—a home where my restlessness can settle, breath by calming breath. It’s not been instant or easy; rather, it’s a slow process of allowing myself to meet and be with the knee-buckling, wordless despair that I fled from so much of my life. What I am learning is that my suffering does not set me apart: it makes me belong. I now know that my being with whatever arises is a purification, a lens polished—often with tears from the past—with which I must stand firm against the waves of segregating myself from the world. Dharma practice is not an escape: it’s an intimate meeting with the discomfort and suffering of the first noble truth. Life contains suffering.

Related: What are the Four Noble Truths?

What I remind myself of daily now, and what often blooms in my meditation practice, is a trust that I can’t not be part of the immensity that surrounds and supports me—my circle of family and kalyanamittas, spiritual friends; the earth, water, and sun by which my food grows; the strangers who truck that food north; the nurses and doctors that look after my health. And so much more. I am not orphaned from this world. I never was.

The author Pat Conroy said, “If a story is not told, it’s the silence around that untold story that ends up killing people.” Fifty-eight years after the Revonoc‘s disappearance, my adoptive mother, Fran, my sister, Aileen, and I held the first-ever memorial service for our vanished family on the shore of Puget Sound, where Aileen now lives. For my sister and me, the occasion sparked an incipient reconciliation. A number of relatives also gathered with us to formally honor our missing in a ceremony, to speak of what we all lost by the Revonoc’s tragic disappearance. A new brass plaque in front of the seaside bench states: “Harvey, Dorothy, Larry and Lori Conover—Sail On.” Before us, a vista of a clear sky and a serendipitous sailing regatta. A fair wind blowing across their transoms, the yachts, wing on wing, glide silently away from those of us admiring them on shore.

As I claim the lost from their drowning, I, too, am claimed. As I gather the shredded ribbons of our family’s grief, I untangle the knots that have so distorted the lives of Revonoc’s orphans. To say Look, really look: This is what happened to us. This is why we’ve stumbled. To know that there is a path of freedom from this suffering in the dharma has allowed me to reclaim my life. “Just as the ocean has one taste—that of salt,” said the Buddha, “just so the dharma has one taste— that of liberation.