Tenzin Norbu Namseling, the sixth Khado Rinpoche, is the son of Namseling, as aristocrat and finance minister of the former Tibetan government. In 1958, the elder Namseling was sent to the south of Tibet to negotiate with the Khampas, or Tibetan resistance fighters, but joined them instead. After helping safeguard the Dalai Lama on his passage from Tibet to India in the historic 1959 escape, Namseling went to Sikkim, where he passed away in 1973.

In Tibetan tradition, each historical Khado Rinpoche is the incarnation of a lama, or holy teacher, who manifests generation after generation in order to be a source of spiritual strength for his people. The spiritual lineage of Khado Rinpoche is embodied in many famous deeds. The immediate predecessor of the sixth Khado Rinpoche was a close friend and ally of one of Tibet’s last regents, Reting Rinpoche, who withdrew from office in 1941 and who was imprisoned and killed four years later when he attempted to resume his government post. Khado Rinpoche was imprisoned at the same time, and his possessions—monasteries, houses, and a hermitage in the vicinity of Lhasa—were confiscated by Namseling on behalf of the government. Released from prison after the death of Reting Rinpoche, Khado Rinpoche went to Changtang, the northern plains of Tibet, where he had several other large monasteries. He passed away there.

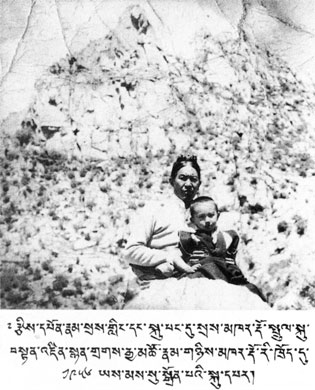

Namseling had five daughters and was ecstatic when finally his wife bore him a son. It is said that he loved this baby very much and carried him around in his arms everywhere, only to find that this beloved son was actually the incarnation of the man whom he had imprisoned, Khado Rinpoche.

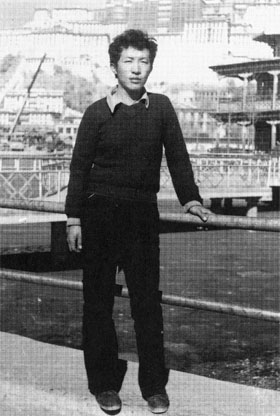

Namseling’s son grew up in dire poverty during the 1960s in Tibet. At the age of 16 he became a political prisoner under communist rule during the Cultural Revolution. He spent three years in solitary confinement. After his release, he found that his mother had been sentenced to ten years in prison because his father had tried to send the family money from Sikkim. Khado Rinpoche then went to work to care for his sisters and family. He still does so.

***

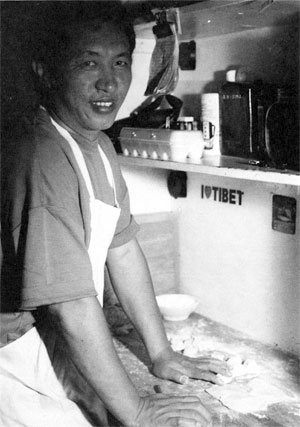

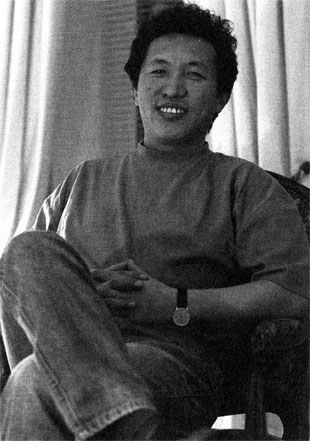

The first time I met Khado Rinpoche was at the Tibetan Kitchen, a small restaurant in midtown Manhattan. He is a quiet, reserved, and unassuming man. His white apron hid his simple Western clothes. I could not help asking myself the obvious question: Why is a rinpoche, a lama, making momos (Tibetan dumplings) and clearing tables in a restaurant in New York City?

The first time I met Khado Rinpoche was at the Tibetan Kitchen, a small restaurant in midtown Manhattan. He is a quiet, reserved, and unassuming man. His white apron hid his simple Western clothes. I could not help asking myself the obvious question: Why is a rinpoche, a lama, making momos (Tibetan dumplings) and clearing tables in a restaurant in New York City?

“Why do they call you Rinpoche?”

“When I was three years old, His Holiness the Dalai Lama chose me to be the sixth Khado Rinpoche. After the traditional haircutting ceremony, I was sent home with my mother. I was too young to enter the monastery.”

“Chose?”

“Yes, he chose me; he recognized me. I grew up during a most difficult time when the Tibetan people were on the verge of war, unable to accept the increasingly brutal Chinese domination. The Khampa resistance was inflicting some damage on the Chinese army in the south of Tibet. My father, a government official, was sent to the south by the Chinese-controlled Tibetan government to stop the fighting. Instead of stopping them, he joined up with the freedom fighters and later on went to Sikkim. We never met again.”

“Do you remember your father?”

“I only remember that he was very tall and stately. I don’t have any memory of his kindness or affection toward me.”

“Your father fought against the Chinese army to defend Tibet’s independence. Would you do the same if you had the chance?”

“Yes, definitely. I would want to join the army and fight.”

When he saw my shocked face, he went on, “Not to kill the Chinese or take revenge, but to defend my people, our country and culture. The Chinese have killed many Tibetans and want to wipe out the Tibetan people. They are committing genocide.

“We did not go to China. They invaded us. I stayed in my country, and the Chinese came, killed my family, and put me in prison. Why? They say the Tibetans want to change the inequality of rich and poor in their countries. This is not the job of the Chinese, it is our job. We will do it. I don’t want to go to China and kill the Chinese; I want only to preserve my country.”

“But then you are not really adhering to the principle of nonviolence, as His Holiness the Dalai Lama teaches.”

“Yes, it’s the same.”

“No, His Holiness is committed to nonviolence under any circumstances. But you are willing to join the army and kill the Chinese, if necessary. So you are not nonviolent.”

“They both come to the same place.”

“The end justifies the means?”

“I am not trying to justify an action for the sake of possessing something or for the sake of power. You can look at the situation in Tibet yourself and easily see who is being victimized and who is justifying wrong deeds.”

“But the Dalai Lama is asking all Tibetans to follow the path of nonviolence, isn’t he?”

“At least 95 percent of the Tibetans, probably more, cannot do the Buddha’s action, like feeding his body to the hungry tigress. Most of us cannot do it. The Chinese are hungry. We, as a country, never said, ‘There are a billion Chinese and they are very poor and have terrible difficulties, so let’s give them our country.’ We didn’t do this. We cannot do this. His Holiness can. Most Tibetans wouldn’t be able to give themselves or their country as food for the Chinese.”

“What does Buddhist practice mean to you? What is the heart of practice?”

“To be a Buddhist means something quite different to Americans and Europeans than to Tibetans. In the West, first you study Buddhism. You try it out once intellectually, and then, afterwards, you develop faith. For us, especially those of us who grew up in Tibet, we grow up believing. Afterwards we study.

“I never studied Buddhism; I know only faith. I pray to the Buddha, to the Three Jewels, that everyone—animals and people—develop the awakening mind and that everyone be happy. I pray that the Dalai Lama have a long life and that all the deities help him fulfill his wishes.

“I don’t know if the Buddhist deities and protectors can help the government, but I believe they help me personally. Tibetans used to make so many offerings to them and have faith in them. Then the Chinese came and ate Tibet. They ate a thousand, thousand mountains; they drank a thousand, thousand rivers. And nobody helped Tibet. Now many Tibetans don’t believe in the protective deities anymore.

“When I was in prison, I prayed that the terrible situation in Tibet would never happen to other countries and other peoples. I saw a lot of people killed. I saw and heard about a lot of people killing themselves. They shot themselves or jumped into the Lhasa River. Some killed their children and then killed themselves.”

“What else did you do in prison?”

“Since I was a political prisoner, every day I had to read the Chinese newspapers printed in Tibetan and write a few pages on what I had read. All political prisoners had to read books by Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao Tse-tung in Tibetan. I only had Mao Tsetung’s four books. I read them three times.

“Each week I had to hand in a few written pages expressing my views. At first, I wrote that Tibet is a free country and what Buddhism means. Then after reading Mao Tsetung, I didn’t think it was such a good idea to write this anymore. So I changed. For three years I had to do this. I couldn’t remember from week to week whether I was using the same words or repeating the same expressions. Sometimes I even copied from the newspapers. They never noticed.

“The first two weeks in prison I was handcuffed with my hands behind my back and my arms tied to my chest. There was a big steel lock on my back and a big block sticking out at each arm from the shackles around my chest, so I could not lie down. I sat on the ground, placed the lock in the corner of the wall, and then leaned against the wall with the remaining part of my shoulder. Then I could sleep a little. My feet were tied with heavy iron chains for eight months. During that time I never took a shower or changed my clothes.

“Food was passed through a small opening at the bottom of the door to my cell. They didn’t open the door, and I never saw who gave me the food. They just shoved it through the opening. I would move it with my feet closer to the cot. Then I would sit down and lift the bowl with my feet onto the mattress. From there I could get my face close enough to eat. That was an accomplishment I enjoyed tremendously. And it was good exercise.

When they first removed the handcuffs, I couldn’t move my arms. They had no strength left. I couldn’t even lift my empty bowl. A Chinese guard came and told me to exercise. It hurt terribly. I tried, but I couldn’t do anything. He said, ‘More, more, try harder!’ After a week of exercise I could hold the bowl again.”

I asked Khado Rinpoche if he had ever discovered the reasons for his imprisonment.

“Between 1965 and 1968, many people had come from Changtang to Lhasa for business or to go to the hospital. They asked after the new Khado Rinpoche and were brought to my home. Every month about ten people would come to my house. They had so much faith. They would begin weeping whenever they saw me.

“In 1968, when I was fourteen years old, two men arrived who had organized a group to fight the Chinese. And then they requested a divination ceremony to determine whether they would be successful fighting the Chinese. They offered a little money, some meat and butter. I was only fourteen and told them that I had not learned how to perform the mo, or divination ceremony. They said not to tell anybody of their visit, and they asked me for my photo and my old clothes. I told them that I needed my clothes. We were very poor at the time. They offered to trade me new clothes for the old ones; so I agreed. Then I forgot about them. “One day in prison, several guards came and asked me, ‘Are you Khado?’ I answered, ‘Yes, I am.’ They said, ‘You should come outside; you need some sun.’ It had been a year since I had been outside in the sunshine. We stayed outside for a while, and then the guard asked me about my family. He was a Tibetan with a Shigatse accent.

He carried a gun and kept saying that the Chinese had done good things in Tibet.

“Then two policemen brought a man from another building. I knew I had seen him before, but I couldn’t remember where. They brought him before me, and he just stood there. He did not look at me but kept his eyes on the ground. I tried and tried to remember who he was. After a while I realized that this was one of the men from Changtang who had come to visit me. Then the policeman took me inside again and told me to think about this.

“Late that night they woke me up and took me to another room. There they asked me if I recognized the man I had seen that afternoon. I told them the truth. They told me that in 1969 a group in Changtang had fought against the Chinese army and that they had all been caught. Several Chinese soldiers had been killed and some Tibetans as well. ‘You instigated this,’ they accused me. ‘But since you were only a child, it must have been your mother who guided you. She is in prison now, and we will kill her for this.’ ‘No, my mother didn’t teach me. I did it, but I forgot about it. Please don’t kill my mother .’

“Then they took me back to my cell and never questioned me about this again. From then on I worried constantly about my mother. Every night I dreamed about her, that the Chinese had killed her. She called to me in my dreams. Then I went a little crazy; I started to hear things.

“I heard voices. It was just like reading a good book, or listening to a great story. I couldn’t pull myself away. I listened day and night. I don’t remember what they said. Whenever I woke up I could not remember anything. Maybe this was the beginning of going crazy.”

“Could they have been voices from your Buddhist past?”

“I don’t know. I don’t believe they were Buddhist deities. Now I think that it was the beginning of madness.

“Sometimes I wanted to die. I wanted to die fast before the Chinese could kill me. I would take out the light bulb and stick my fingers inside the socket, but I wouldn’t get a shock since I would be standing on the wooden box that I used for a latrine. I jumped down from off this box many times—head first—trying to kill myself. I hit my head against the stone corner, but I never even got hurt.

“After I had started to go crazy, one day I broke the glass window. I wanted to die and screamed, ‘Please kill me! Please kill me!’ I called out many times. Then, at night, the Chinese came, grabbed me, and beat me. They took me to another room with only Chinese army officers, no Tibetans. They tied my arms behind my back so tightly that it hurt a lot. After half an hour, my body was numb. They told me to stand up. I stood up and began to hurt again. But after another half hour, I no longer hurt. My body was numb again. It I felt very thin and pointed, I like the edge of a very narrow ship’s bow. After two or three hours, they took off the ropes and massaged my arms. I couldn’t lift my arms at all. I tried to stand up, but I couldn’t. A Chinese soldier caught me as I fell. Then they talked among themselves. I didn’t understand what they were saying. One Chinese soldier called to me. He said something I could not understand. I turned around to look at him when he called me a second time. Another soldier sitting on the floor close behind me asked, ‘What are you looking at?’ He hit me over the head with the heavy chain that bound my feet. Then I forgot everything.

“After a few hours I woke up and thought I was at home. I was feeling a little sick and uncomfortable, but I thought I was in my bed at home. Then I looked around and saw that I had footcuffs and handcuffs on and my clothes were all wet from the water they had poured over me. My head was wet, too. There was a lot of water everywhere, and I was cold. Then I tried to move while I was lying on the cot. It hurt. I was thinking and thinking about what had happened. I cried a little and thought, I am only 16 years old, why are they doing this to me? I never killed anybody. I never lied. I thought about my mother in prison and got very sad. Then I cried. I called on the sky, but nobody answered. I thought, maybe it will be like this for another month or two, and then they will kill me. I felt my head hurt and noticed the smell of blood. I moved a little bit, and I hurt all over. “Later I thought, the Chinese are doing this to so many people. There are more than a billion of them. How long can they keep on doing this? Some day they will have to change. “One day things did change. I no longer wanted to kill myself. I thought, I am still young. The Chinese government will change eventually.”

I asked him whether he had ever had a chance to meet other prisoners.

I asked him whether he had ever had a chance to meet other prisoners.

“Not really. When I was first imprisoned and taken daily to interrogation sessions, I once saw a man leave the police office guarded by Chinese soldiers. He was very thin, wearing glasses and good clothes. I thought he must be Reting Rinpoche. He smiled at me. The guard said, ‘You know who that is?’ I said that I didn’t, since I had never seen him before. The guard said, ‘You are lying; you know him.’ And he beat me.”

“How did you know it was Reting Rinpoche?”

“I don’t know. The thought just came to my mind. We went to prison on the same day and were released on the same day.”

“Did you have a chance to talk to anyone during those three years of solitary confinement?”

“No, never. But I watched and listened to the birds. A wall surrounded the compound where my cell was located. In between the wall and my window, there was a space about ten feet wide where weeds and wildflowers grew. The birds flocked to this space. I listened to the birds, and soon I could understand them. I could understand when one called to his friend to tell him he had found a bug. They would laugh and tell their friends when they were happy. Each had a friend, and I soon knew who was whose friend. As soon as one appeared, I knew his friend would be soon to follow. The same friends always came together. There was one bird who had only one leg. He always came alone. I also knew when the birds were about to fight, not only on account of food but also friends among themselves.

“One day the Chinese police called to me. When I arrived at their office they told me that I could leave that very day. They also told me that my mother was in prison, that she had not been killed, and that she would have to stay in prison for ten years. They told me that since I was young I should go and work. I was given a ration card and told I could stay in Lhasa.

“In exile in Nepal, India, and in the United States, many Tibetans say that I think like a communist. They say, ‘He has changed. He doesn’t belong to Buddhism anymore.’ To be critical in a fair way can be an important Buddhist action, not necessarily communist. I believe in the Buddha. I just don’t believe in rich monasteries, because I don’t think his is what the Buddha is about.

“In Tibet so many misunderstandings have arisen from religious dogma. For example, if a rinpoche gives up being a monk and gets married but keeps a religious mind, all that people talk about is the fact that he gave up being a monk. On the other hand, a Tibetan who works for the Chinese and has a communist mind, even if he has killed Tibetans before, if he shows religious behavior, such as going to the temple and prostrating himself, many believe he is religious and good. I think he is just looking out for himself. During the day he works for the Chinese—not in the way that all Tibetans are forced to work for the Chinese now, he likes and believes in the Chinese. In the evening he shows a religious face. There are many such examples of wrong religious behavior.”

“You have the same name as the famous Khado Rinpoche. Do you believe you are the incarnation of that lama?”

“I don’t know. Maybe I am the reincarnation, maybe not. In Tibet when people approached me with reverence, I didn’t pull away. If I had turned away from them, maybe they would have gotten angry. They might think because I am called Rinpoche, I know everything. But I know what I know. It is limited, and I always tell the truth about that. If I say I am not the incarnation of that rinpoche, what about the fact that His Holiness the Dalai Lama chose me? He knows. But if I am the incarnation of that rinpoche, I don’t remember anything. So you see, I can’t decide. That is the truth!” He laughs.