Not so long ago I had just finished pruning a beloved Black Mission fig tree when breaking archaeobotanical news rocked my world. A handful of charred figs, carbonized and unearthed in the ruins of a burned village north of the ancient city of Jericho, pushed the known dawn of agriculture back a thousand years to 9400 B.C.E. Not just that, but these same Fertile Crescent figs proved to be a variety that grows only on sterile female trees. Prior to their discovery the first evidence of settled human history was believed to be the domestication of seed-bearing grains and legumes around 8400 B.C.E. Now, with the uncovering of these Neolithic figs, which can be reproduced only by planting vegetative shoots cut from the limbs of a sterile mother plant, a sophisticated culture of prehistoric gardening was revealed.

Plant propagation has long been my gardening passion, especially sowing ripe seed on dark ground. But the Jericho figs remind us of an older buried truth—that new plants can be regenerated asexually from even a single cell cultured with mindful attention. Knuckle-sized joints of pale gray figwood inserted in living earth will push out an adventitious system of fresh roots and grow a new tree identical to its sterile mother. And a piece of stem and a root can be grafted together in the most primitive fashion to form a new and continuous vascular connection.

Why be surprised? The fig is one of the oldest and most varied plants on earth. A member of the vast mulberry tribe, the fig and its seven hundred varieties—from the giant Banyans of India to milky-sapped rubber plants, including a substantial array of delicious edible figs—are all related to the ancient fruit uncovered near Jericho. All figs derive from a common ancestor, Ficus carica, and from the cultivated subspecies sativa, or the domestic fig. Originating in Syria and extending to the Canary Isles, figs provide all Mediterranean countries with rich fruit, thriving in the Far East and India as well as across the Americas.

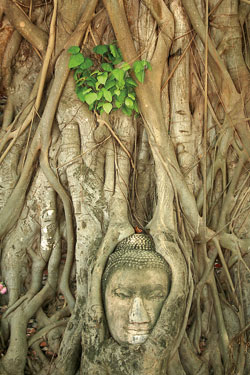

The fig features prominently in the religious and mythological history of the world. In Asia, tree spirits and demons were believed to inhabit figs. As the first plant named in the Bible, fig leaves provided Adam and Eve with their original aprons of modesty. The Roman scholar Pliny tells of an immense fig tree sheltering the infant twins Romulus and Remus while a she-wolf suckled them under its branches at what was to become the founding site of Rome. And the Mahabodhi tree in the ancient Sri Lankan capital of Anuradhapura, said to be the oldest known tree on earth, was grown from a branch plucked in 288 B.C.E. from the ancestral Bodhi tree under which the Buddha sat. Carried as a gift to Anuradhapura, this Ficus religiosa was planted by Emperor Ashoka’s daughter, the nun Sanghamitta.

In the Green Gulch Farm glasshouse we have a small bodhi tree grown from a cutting taken from this same Anuradhapura ficus. I cleaned the elegant heart-shaped leaves of this bodhi tree yesterday, feeling an old kinship with all gardeners who have tended figs for over eleven centuries. And even though Suzuki Roshi encouraged Zen students to leave no trace of themselves in the wholehearted practice of the way, I am proud to trace my lineage as a gardener through a vast sangha of figs