New England summer breathed around me as I settled into silence at the Forest Refuge. On the morning of my second day here I wandered about, learning the layout at this retreat center hidden deep in the woods near the main buildings of the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. On this breezy warm day, the forest beckoned.

I started out on a wooded trail, enjoying the breeze, the interplay of light and shadow on the path. The trail made a circle, bringing me back by way of the meditation hall, where I saw a few stones set in the earth. Flat in the grass, they were carved with people’s names and a brief identifying message. No one I knew.

But something drew me to walk the circuit a second time, until I found myself once again behind the meditation hall. Here I happened to look down. Embedded in the earth before me was a big gray rock, maybe two feet long, a foot and a half tall. Chiseled into its face were the words

BELOVED TEACHER RUTH DENISON 1922—2015

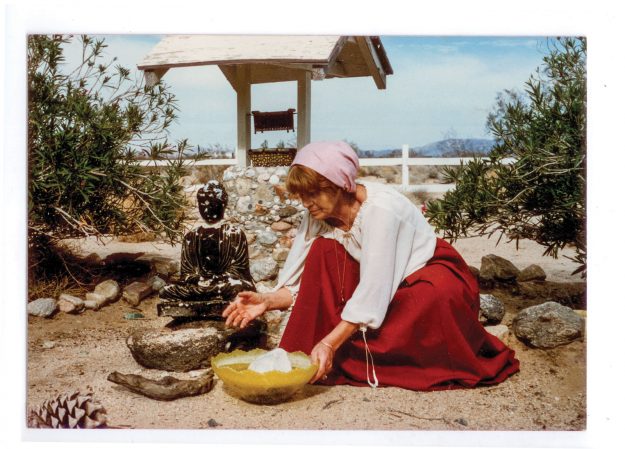

Stunned, I—who almost never cry—erupted in tears. Here was a memorial to my teacher of 35 years, whose home was so far away in the Mojave Desert of California but who had been one of the original teachers when IMS was founded in the 1970s and had continued to teach there over the years.

How right it felt that Ruth Denison should be remembered here with the words “Beloved Teacher.” Ruth’s whole purpose, in the more than 35 years I had known her, had been to bring the dharma to anyone who would listen. Leaning over the stone, I let myself cry until there were no more tears.

Each day at the Forest Refuge I visited Ruth’s stone, where I discovered some of her ashes rested, and always there was a suggestion of what she had offered us in the decades of her teaching and practice with us.

I sat on the damp earth, leaning against the bark of a maple tree, remembering how much Ruth had wanted to awaken in us the awareness that we are more than these little selves we inhabit every day, that we express the flow of the universe, spacious and deep and all-knowing. So there in the woods I thanked her for believing in her students so much. On my Sunday visit to the stone there came the inkling of the little German farm girl she had been, walking to the village church with her family— Ruth as a person, with a childhood, a history that had formed her. Another day as I sat at Ruth’s stone I felt the spirits of the forest dancing in the breeze, in the fluttering of leaves, the gentle dipping of branches. Ruth had introduced movement and even dance into the austere early environs of Vipassana practice in America; she had been variously loved or criticized for her innovative, eccentric, creative teaching.

Ruth’s memorial stone put me in touch with my lineage—with the actual living teacher who had welcomed me onto the path and illuminated the dharma for me during many years. This awareness I took with me recently to Dhamma Dena Desert Vipassana Center (now Dhamma Dena Meditation Center) in California, hoping to reconnect with my spiritual home. There against the great expanse of desert sky, the distant mountains, the persistent breezes of winter, stood the low modest buildings where so much emotion, effort, love, resistance had expressed itself.

I knew that the new resident teacher emphasized an expanded and inclusive consciousness. She worked to accommodate disabled retreatants, to welcome people of color, to recognize and respect gender fluidity. This teacher, a friend, had sent me photos of the concrete walkway that had been installed so that a person in a wheelchair could go comfortably from the main building to the meditation hall, and I knew there would be many other changes.

I remembered how much Ruth Denison had wanted to awaken in us the awareness that we are more than these little selves we inhabit every day.

But as I planned my journey, I found myself wanting to bring something of Ruth into this developing environment. I found the photo I had taken at Forest Refuge showing the memorial stone. I imagined offering the print to be hung in the meditation hall, among the plaques and commemorations Ruth had received. I would make a label identifying it, and it could become a permanent feature. Perhaps I would frame it.

On the long drive from the Palm Springs airport to Copper Mountain Mesa just above Joshua Tree, my driver told me about the current travails of an aging man I knew well who had been part of Dhamma Dena from its beginning. So I began my week focused on the needs of a particular suffering human being, a reminder that this center had never been just about meditation. Ruth had earned a reputation in the Vipassana meditation world for accepting everyone at Dhamma Dena, even seriously disturbed individuals, and as retreatants we were invited to respond with kindness and patience to guests who sometimes acted disruptively. Added to this group was the occasional person struggling to overcome a drug or alcohol addiction, or someone who had come to the desert to die. Ruth accepted each one with their own needs, integrated them into the retreat schedule as much as they could tolerate, and worked with them privately.

Related: Why Grief Is a Series of Contractions and Expansions

Arriving at Dhamma Dena now, I was struck by the actual physical sight of the wide concrete walkway from main house to meditation hall. How strange it seemed, as I remembered my experience of walking on the crumbly high-desert soil, grit creeping into my shoes, the sound of my feet scraping sand as I approached the meditation hall. There was something unlikely about this wide concrete walkway— could it really be here? I remembered that Ruth sometimes found herself disabled by injury or illness as she aged, and how she had responded. Once, having broken her hip, she came to the meditation hall carried on a door held aloft by four of her students: Ruth made the most of this conveyance, lolling back like a concubine on a litter, grinning and languidly waving at those of us who crowded at the windows to watch her approach. In the face of emergency, Ruth improvised, she invented, and she invited anyone to join her in playing with the circumstance. Nothing fixed, or rigid, or predictable— all flowing to meet the moment with as much joy as might arise in us. So I was of good cheer at being here, until my first entry into the meditation hall.

The beautiful, peaceful room was empty, as everyone else was gathering for dinner. All seemed in its usual order—until I approached the altar and began to feel uneasy. What was the problem here? I stopped, looked at the place immediately in front of the altar, and was hit by the absence. Something crucial was missing.

The day after Ruth died, back in 2015, someone had brought a small embroidered cloth of green and silver and spread it out just before the altar, facing the Buddha statue. On that cloth, they had carefully placed Ruth’s knitted booties, her knitted cap, the beads of her mala, a silver cup filled with the dried rose petals we had placed on her body before she was taken away to be cremated, and two photographs, one of her Burmese teacher, U Ba Khin, standing before his white-walled Rangoon temple, the other of Ruth—vibrant, probably in her sixth decade of life, smiling out at the world she loved so much. This little arrangement brought her presence to the altar. It had perhaps become a sort of shrine to Ruth. I had been drawn particularly to the booties—their whimsical, intimate message—yes, this was a real human being with feet toughened by so many years of desert walking, whose flesh found comfort and rest in the knitted slippers.

Now I stood before the altar and saw that the cloth and its precious objects had been removed. There was only the formal altar with its Buddha and Kwan Yin statues, vases of flowers, a small photograph of Ruth in Burma.

I stood transfixed, confused—how could this have happened? Who made this decision? Who carried it out? Where were the objects kept now?

Something slid sideways inside me, the way a house displaced by an earthquake slips off its foundation. I understood that the changes taking place at Dhamma Dena were not minor fixes and simple steps of tidying-up, but transformation into a new way of seeing the world.

As I turned to leave the meditation hall, I thought of the Forest Refuge photo in my suitcase and remembered the little speech I had composed on the airplane that I thought I might give in offering the photo to the meditation hall. Now it would stay in my suitcase. Arriving, I had noticed that a third to half of the retreatants were “oldie moldies” (Ruth’s term for longtime students) like me, those who had sat with Ruth and helped build Dhamma Dena. But the other participants glowed with youth—some had never been in a Buddhist setting before—and were eagerly receiving or resisting the teachings with beginners’ enthusiasm. I envied them the purity of that first touch with the dharma.

That night at the evening session, I sat at the back and looked particularly at the oldie moldies. They had chosen to sit in the comfy chairs; this I understood, for after 30 years of sitting in meditation posture on a cushion on the floor, I too finally had to surrender to the complaints of my knees and back and sit on a chair to meditate. Their hair was gray, their faces lined, each of them so distinctly embodying the young people they had been at the time when we all found Ruth, yet now expressing the reality of the later years of life when skin sags, senses dull, energy lessens. And the earthquake rumbled again in my chest, to shake me with a brutal thought. It was incontrovertible, it was utterly self-evident: When Ruth’s original students all die, there will be no one in this world who knew her. That lived presence will disappear and there will be only the secondhand experience of audiovisual recordings and written text. I lowered my head, feeling the loss in this.

When I asked our current teacher about the removal of the “shrine,” she responded casually, saying she had placed the booties and other memorabilia behind the screen where the chant sheets and conga drums and other items were kept. I was left to speculate on her reasons and be grateful that Ruth was often mentioned, some of the songs she used to lead were introduced, and a large photograph of her hung on the side wall. That was enough for this new configuration of students.

As the days of the retreat moved on, I stayed attentive to the changes, watching the young students respond to our teacher, seeing that the old really does— in so many tangible ways—have to give way to the new. Who deserves to fill the mental/emotional/physical space? Those who are alive in it, engaged in sustaining and creating it. Those who carved out and inhabited the space from the beginning now need to find a way to support the new ideas, facilitate the new direction.

Still, I missed the knitted shoes, remembering what it had been like to see them there before the altar. Was this why religious folks keep relics of their saints and teachers? I can imagine that saints exist, but I’ve never met one, only encountering variously gifted and flawed human beings doing the best they can. Ruth was obviously not saintly, willing as she was to let us see her faults enacted in real time. Although this openness could be hard to accept at times, the effect was to deepen awareness of her great good qualities— her love, her joy, her spontaneity, her boundless compassion, and her grasp of the dharma. Now I begin to realize the power of the physical remnant— garment, implement, jewelry, tool—to suggest the actual living presence of that actual living human being.

Related: Practicing with Loss

And I am left asking, In a lineage, what is it that is passed on? The answer to this question becomes incredibly complex and articulated over time as one participates with the teacher and other human beings in dharma practice and just plain ordinary life. The experience becomes so multifaceted and nuanced that it is inexpressible.

All this I was revisiting in my retreat days, until in one moment I encountered a memory that shook me. A Korean film I had seen many years ago tells the story of two men, a Zen priest and his student, who live together far from civilization. The teacher is strict, supportive, inscrutable: he is the student’s whole world. When the teacher dies, we watch the student bury his body. Then he takes his teacher’s robe and ceremonial apron and, with loving care, folds them into a bundle. Watching the film, I anticipated that he would place it on the altar or on the teacher’s seat in the tiny zendo. But instead, the monk opens the door to the stove, where flames dance, and places the robe in the fire, where we watch it being totally consumed.

I am not there yet, Ruth. Not ready to let you go.

And yet I also hear your voice saying, “Human beings are rivers of constant movement and change, arising and passing away.”

Those words bring with them the face of Ruth at her most tender, smiling at me with ironic cheerfulness, inviting me to stay with my this-moment awareness, to feel the pain of loss, always opening the space for joy, and to learn to go with the river of change—arising, as she had arisen in my life, and passing away.