Tricycle readers with a penchant for reality television (there may be more than you’d expect) were given a pleasant surprise in November when the magazine made an appearance on the mainstream reality TV show Queer Eye: We’re in Japan! In the show’s second episode, “Crazy in Love,” the hosts counsel a young gay man who struggles to open up about his sexuality to his family. Partway through, the hosts connect him with Kodo Nishimura, a Buddhist monk and makeup artist, who refers to Tricycle’s Q&A with him in the Fall 2017 issue as a way to share how he, too, had to overcome the challenge of tradition in order to accept his passion for makeup.

Kurt Spellmeyer, a Tricycle contributing editor, Zen priest, and professor of English at Rutgers University, left a comment on Facebook:

In my opinion, it is vitally important for Buddhists to recognize that these struggles for freedom are not tangential to the dharma. The freedom on display here is what the dharma is all about. All authoritarian cultures believe in an essential self that we must not destabilize or abandon. But the message of the dharma is that there is no essential self. We are free to create ourselves, and, eventually, we will want to want to create a self that puts the freedom of others first. ♥

In response to David Schneider’s lighthearted short story in the Winter issue about a Buddhist publication’s accidental misidentification of the author’s sexuality (“No Good Deed Goes Unpublished,” Winter 2019), “Jenny Everywhere” shared a different experience she had when discussing her sexuality with a Buddhist monk. After Jenny mentioned to the monk, a Tibetan Buddhist teacher, that she was a member of the LGBT community, the monk replied that homosexuality constitutes a form of sexual misconduct as outlined by the Buddha. “In his eyes,” the story continued, “no gay person could truly be a Buddhist.”

Reader “Camille” was fast to respond, adding, “It seems an unfortunate fact of life . . . that religious people who get caught up in their specialness sometimes lose track of reality and can be quite arrogant and, as was so clear in this case, harmful.”

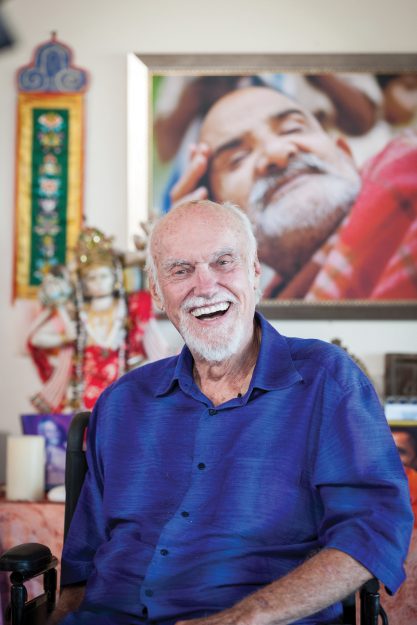

Following the death of the counterculture icon and spiritual teacher Ram Dass, Tricycle readers poured out tributes across all of our platforms. Some readers criticized our obituary for neglecting to mention that Ram Dass was gay. The omission “reproduces the homophobic erasure that’s so often faced us,” wrote Jesse Oliver Sanford. In response, Gabriella West, invoking our own editorial discussions, questioned whether or not Ram Dass’s sexuality was central enough to his role as a public figure to merit recognition. Others shared memories of meeting him, or of the impact he had on their lives. Martha Faketty wrote “Ram Dass’s books changed my life. . . . They were a guide to my early spiritual journey—and still I return to certain passages and quotes that I copied for myself, for the wisdom he embodied and expressed through his writings and life was profound. Enduring love.”

Over on Trike Daily, when the mindfulness-based cognitive therapy advocate Mark Leonard asked, “Who Is Misrepresenting Mindfulness?” (tricycle.org, Nov. 14, 2019), he set off a flurry of engaged readers’ comments on the dangers of presenting mindfulness in secular contexts. In the article, Leonard critiques a popular approach to mindfulness that considers mental ailments as aspects of one’s dysfunction; he pushes instead for a socio-psychological approach, one that examines an individual’s suffering as part of a larger cultural whole. Reader “Hannah,” who identified as a mindfulness teacher, expressed discomfort with the popular description of mindfulness as a “calming” practice. “Despite the fact that it does have that impact,” she wrote, “this tends to confuse people with regard to the purpose and expectations of the practice.” That purpose, she wrote, is the direct awareness of anatta, or “non-self,” an experience that can trigger perhaps unnerving existential questioning. “This does not mean that there is no one there, or that we must relinquish our context or pretend that our experience as an individual doesn’t matter.” The experience of non-self, she continued, “allows the freedom to explore how we interact with our environment with more clarity … than when we are caught in erroneous ideas and perceptions that we take for granted as being ‘who we are.’” Hannah’s comment was just the beginning of an extended conversation about why and how we practice mindfulness. Check it out!

The Question

Did you encounter Buddhism or meditation first?

I first practiced meditation around the age of 6, emulating Master Splinter from the Ninja Turtles. There’s a scene in the second movie where it’s pointed out that he has been “meditating many hours.” I got curious about meditation after that, and would challenge myself to sit in silence on my bed for as long as possible; usually just a few minutes, but I remember one time being surprised that an hour had passed.

—Matthew Zimney

Meditation and yoga, as a refugee to the US in 1956, to survive the physical and emotional trauma I experienced in Soviet-occupied Hungary as a child.

—Rose Nagy Ostrander

Buddhism, discovered by accident when I came across a book by Thubten Chodron: Open Heart, Clear Mind. That was what I was working toward, so I bought it. I was ready, and the teacher appeared to me.

—Teri Wehmeyer MacGill

I became a Buddhist in 2008 but hadn’t meditated until about three years ago. I became frustrated and quit for a while when I realized there are so many different ways to meditate, but finally chose what I thought were the best ideas from everyone and put them together to make my meditation ideal for me.

—Sheila Ryan