One wintry day in the late sixties, when I should have been studying for finals at college, I took a bus 150 miles to a dowdy New York City hotel room to get my very own mantra from a pale young man with a vaguely Scandinavian accent. I remember how, in those heady days, it seemed not only possible but highly probable that the right mantra, koan, or guru could allow one to leapfrog easily over one’s neuroses and “hangups” (as they were then called) into nirvana—or something like it. After all, the Beatles had gone to India and we had seen Dr. Richard Alpert metamorphose into Ram Dass. Of course, spiritual practice turned out be a lot of long, hard work, and my neuroses are still pretty much intact.

These days, my ideas about how to improve myself might incline more toward medication than meditation. Might I be a better person on Prozac, the wish-fulfilling gem of the nineties? In a description that sounds a lot like New Age pitches for Eastern mysticism, psychiatrist Peter Kramer, the author of Listening to Prozac, writes, “Prozac has the power to transform the whole person—illness and temperament. When you take it, you risk widespread change.”

Of the fifty-million-odd Americans on Prozac or one of its cousins, a few thousand, let’s say, must be practicing Buddhists. That’s just a guess, but anyone in denial about Buddhists on Prozac would have been brought up short at the 1998 conference of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy in Boston. There, a respected Zen teacher stood up and described his struggles with clinical depression, his unsuccessful attempts to dispel it with practice, and his eventual relief with a Prozac-type antidepressant. “When a Zen master says this at a conference, it’s a big shift,” says therapist Boston psychotherapist Philip Aranow, president of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy. There are other dharma teachers who, like many practitioners, still relate to Prozac as a taboo and resist any public disclosure.

Ten years ago, or even five, a Buddhist student struggling with the symptoms of depression would most likely be prescribed more dharma. “You’d be told, ‘You’re not practicing enough,’” recalls Curtis Steele, a psychiatrist in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who is a member of the Shambhala community. “I think that’s changing, although there are still born-again Buddhists who think meditation is the answer to everything.” Yet a drug such as Prozac poses a special problem for Buddhists. If one’s object of inquiry is the mind, then the question becomes: Does altering this landscape affect the nature or efficacy of practice? Can Prozac help or hinder this process? Also, the question is tinged with a moral quandary: If I decide in favor of Prozac, am I somehow “cheating” in my practice? Or, if I need such a drug, have I failed in my practice?

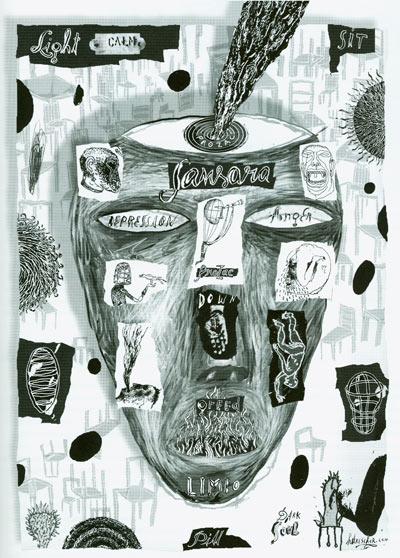

The compass for practice is set by the Buddhist concept of original enlightenment: Enlightenment is not a matter of adding anything but rather of peeling away the false, fabricated sense of self to allow the innate Buddha being to emerge. In contrast to the self-centered, separated small mind, big Mind is unfettered and boundless, purified of greed, anger, ignorance, and all defilements, as clear and stainless as an empty mirror. For some Buddhists, Prozac—or any deliberate alteration of the mental landscape—automatically adds another layer to the mind’s “obscurations,” pushing clear Mind further from reach. And despite the new general acceptance of Prozac by Buddhist teachers and therapists, among students there still exists a widespread belief that the mind on Prozac, however “realized,” cannot be “pure.” An alternative view is that whatever state the mind is in—greedy mind, angry mind, in-love mind, or Prozac mind—that is the mind that one must work with, and it is the concept of “purity” that creates further obstacles.

One Buddhist teacher tells a story in which, several years ago, a dharma friend confided to being on Prozac. The teacher, believing that Prozac hindered a “pure” mind and added to delusional realties that made facing life’s big ordeals even more difficult, asked, “And what are you going to do in the bardo?” Now, the teacher, laughing at her own folly, says that she would never say that.

Susan Morgan, of Boston, who is both a Buddhist and a clinical nurse specialist who prescribes antidepressants, tells me, “When I work with meditators, they ask questions like, ‘What is the self that I am medicating?’ I don’t have an answer to that, but it’s very interesting sitting with the question.” The question is remarkably similar to, “Who is the self that is meditating?

From the point of view of “who is the self,” each of the major schools of Buddhism prevalent in the West contains orthodox elements inimical to antidepressants. In the Theravada tradition of southeast Asia, for example, a narrow interpretation of the Fifth Precept lends itself to rejecting antidepressants as mind-altering intoxicants. In traditional Asian Zen, the psychological self is not an appropriate subject for study. In contrast, the Vajrayana practices of Tibet include examining one’s own anger, greed, and fears and making them grist for the mill. When Tibetan Buddhism first took hold in the United States, during a therapy boom, there was a widespread sense among Vajrayana students that their practices precluded a need for therapeutic help—verbal or pharmacological.

Fluoxetine hydrochloride, or Prozac, was unleashed on the market in 1987, quickly becoming a extraordinary cash-cow for its maker, Eli Lilly. A stream of Prozac “wannabes” followed, their very names (Zoloft, Paxil, Luvox) suggesting sublime lassitude, or levitation above the turmoil of samsara. Every day there are more antidepressants in the family known as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (or SSRIs), a term coined by SmithKline Beecham, maker of Paxil. SSRIs are designed around serotonin (chemical name, 5HT), a natural chemical found in large concentrations in the gut walls, the walls of blood vessels, and in blood platelets, as well as throughout the brain. Neurons (brain cells) communicate by means of chemical messengers, such as serotonin, which are released into the small gap, or synapse, between neurons. After being released into the synapse, the serotonin must connect with specially designed receptor molecules on the postsynaptic cell to transmit its message. SSRIs are supposed to enhance the amount of available serotonin for a longer duration by inhibiting the reuptake of the chemical by the presynaptic neuron. The hype about SSRIs is that they “target” serotonin neurons cleanly and efficiently, without scattershot effects on other neurotransmitter systems such as norepinephrine or dopamine. Whether this is actually true is another matter.

There is an old science writer’s axiom that any new medical treatment can be guaranteed to generate two headlines. The first is “Treatment X is a miracle cure”; the second, a year or so later, is “Dangers of X Revealed.” So it is with Prozac and its cousins. With the enormous success of Listening to Prozac, Dr. Kramer became the Pied Piper of the newly minted SSRI, hailing it as “a designed drug, sleek and high-tech,” that “comes from a world even most doctors do not understand.” Because patients do not normally feel “drugged” on SSRIs, he asserted, these nouveau antidepressants could be prescribed for “less ill patients”— patients who do not meet the criteria for major depression but suffer from a kind of chronic melancholia known as dysthymia. It was primarily among such patients—with dysthymia, anhedonia, social maladroitness, and, especially, “extreme rejection sensitivity”—that Kramer observed a phenomenon of fairytale proportions. On 20 milligrams a day of Prozac, some of these people didn’t just emerge from depression but underwent profound metamorphoses. Before Prozac they were self-effacing, timid, inhibited wallflowers and milquetoasts; after Prozac they were the life of the party, the head salesman, the belle of the ball.

Not long afterward came the backlash. Suddenly, haunted “Prozac Survivors” were appearing on talk shows and the Internet with tales of suicide, murder, self-mutilation, mayhem, or just very, very bad relationships attributed to SSRIs. Talking Back to Prozac by Dr. Peter R. Breggin, M.D. features a shopping list of SSRI fiascoes (“A woman who held her psychiatrist ‘hostage’ with a razor to her own wrist sued Lilly concerning self-mutilations inflicted while taking Prozac”) and charges that Prozac is a toxic drug that leads to long-term neurotransmitter disruption.

These horror-story effects do not seem to be common—a recent study in the American Journal of Psychiatry laid to rest the rumor that SSRIs were responsible for a rash of suicides—but neither are the drugs responsible for the magical personality makeovers described in Kramer’s book. “I have a caseload of two hundred and thirty patients,” says Jack Engler, a prominent Boston-area psychotherapist and Vipassana teacher. “I keep waiting to see a case like that. I never have.”

Mark Epstein, a New York psychiatrist, practitioner, and author of Going To Pieces Without Falling Apart, concurs. “I haven’t seen anyone become better than they ever were. If you’re not depressed all you get when you take Prozac are the side effects—nausea, headache, sexual dysfunction.” (Yes, Virginia, SSRIs do have side effects—milder than those of earlier antidepressants but troublesome enough that twenty percent of patients discontinue the medication soon after starting.) None of the psychotherapists I interviewed had witnessed Kramer’s “better-than-well” phenomenon, though the prominent transpersonal psychiatrist Seymour Boorstein, who is on the faculty of the University of California, San Francisco, reports striking, transformative change in some patients.

For years before she considered Prozac or realized that she suffered from recurrent depression, my friend “Jan” (not her real name) was drawn to ten-day retreats. But watching her own mind was like climbing a very sleep slope, or sometimes like clawing her way out of a claustrophobic cave. “I was really committed on retreat. I’d always be up and meditating at four a.m., and I’d meditate whether I felt good or bad. Typically, I’d go into this huge despair and I’d watch my mind, and I’d cry, and many times I would move out of it after a while.

“On one retreat I felt as if I had leather belts around my chest that were being cinched tighter and tighter. I was in intense emotional and physical pain. I wish I’d gone up to speak to my teacher about it. I wonder what he would have said. I just thought, ‘Well, he says if I just sit and watch my breath and feel the feeling it will go away.’

“When I came home I was like a wild woman, filled with rage and despair. I’d say to my boyfriend, ‘You have to go on a Vipassana retreat; it’s so great!’ and he’d say, “This doesn’t look like an endorsement.’”

It is not uncommon for practitioners to feel that “coming out” about Prozac risk being judged as failures in their practice. Yet the one Buddhist therapist I found who spoke out against Prozac talked of the conflict in thoughtful and nondogmatic terms.

“If one undertakes this spiritual path one will find oneself before long in the desert, where everything that once seemed attractive becomes empty or even repulsive,” says Bernard Weitzman, who practices “contemplative psychotherapy” in New York City and is on the graduate faculty of the New School for Social Research. “Depressed people are hyperrealistic; they see things as they are; they no longer have the juice to escape into fantasy. You can be depressed about it—or you can be curious.”

Observing his teacher, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, drunk but philosophically trenchant, convinced Weitzman that the mind is not chemical, and neither is depression: “Well-being is not ruled by serotonin.” Rather, he favors the cognitive behavioral view of depression as the fruit of a particular, flawed belief system (“Things go wrong because there is something wrong with me”) for which the best cure is—ultimately—dharma. “The basis of all Buddhist practice is integration of every level of functioning,” he says. “No aspect of one’s mind need be feared or obstructed. When you befriend all these tendencies, when you’re willing to sit there in maitri practice and see, hear, and feel all that internally generated misery, then you become a person who is trustworthy to herself. A person who is not willing to include the texture of depression in her emotional space is not going to be compassionate.”

“What Prozac does,” he adds, “is make you care less; the burning issues become very attenuated; some people say they are changed in funny ways. A different personality takes the driver’s seat. I think it’s a disaster.”

Does this purist view mark Weitzman as part of the old guard in his community, or has he held out bravely against the inroads of an Americanized conception of enlightened mind?

In support of Prozac, those who have suffered from clinical depression report that it resembles an ordinary bad mood or ennui about as much as the sinking of the Titanic resembles an unpleasant Atlantic crossing. Patients with major depression describe a world apart, an alien land where no birds sing—a blasted, desertlike landscape or a frozen tundra. “I felt it was an entirely different experience from ordinary unhappiness,” says Minneapolis Zen practitioner Philip Martin, author of The Zen Path Through Depression (HarperCollins San Francisco, 1999), an insightful book that includes techniques and guided meditations, drawn from his experience with Zen practice and his own major depression, for healing and/or working with the pain of depression. “My body felt heavy, my sleep patterns and all my body systems were changed. I felt there had to be something more to it.”

“Terry N.,” another practitioner who did not wish to use her real name, is a driven, successful entrepreneur in upstate New York who is also a long-term Zen student. She was blindsided by depression not long after her fiftieth birthday. “It came on suddenly —a total surprise,” she recalls. “I had always been a totally peppy, upbeat, take-charge person. I was a problem solver. I ran a company. I had little sympathy for people who were depressed.” Her first symptom was crushing fatigue, together with a physical slowness and clumsiness so severe she feared she had a neurological disease. Then her familiar world turned barren, stark and tasteless. “Things turn to ash in your mouth; you feel an exaggerated weltschmertz; nothing gives you pleasure; life seems ‘nasty, brutish, and short.’ I thought, “How did I get here? What happened to my beautiful life?’”

After a few weeks on an SSRI she surfaced from her depression; but now she was buzzing, and her zazen was affected. “I got this tremendous surge, like caffeine, which stirred up thoughts and ideas. I had agitated, random, distracting thoughts and a ringing in my ears. It was really hard to meditate, hard to settle the waters. At first I couldn’t count my breath for even ten seconds. It was almost like being a beginner again.” After her brain adapted to the antidepressant, the buzziness subsided, and her mind settled down.

One comment I heard again and again is that depression makes it difficult if not impossible to practice—which is not surprising given that “inability to concentrate” appears prominently on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale used by psychiatrists in diagnosis. “I felt as if I were drowning,” Martin, Zen Pathauthor, remembers. “It was next to impossible to meditate because of the restlessness—the terrible thoughts rolling through my mind. An antidepressant can bring your head above water so you can look for other ways to help yourself.”

When “Jan” started on Prozac eight months ago, she didn’t even try to meditate. “I just thought, ‘If I sit and meditate, I’m not really meditating.’ But then I tried it and I found I could meditate better. I look forward to going on a ten-day retreat now; I’m wondering if I will have a deeper experience because the anxiety that used to come up will be gone.”

When “Jan” started on Prozac eight months ago, she didn’t even try to meditate. “I just thought, ‘If I sit and meditate, I’m not really meditating.’ But then I tried it and I found I could meditate better. I look forward to going on a ten-day retreat now; I’m wondering if I will have a deeper experience because the anxiety that used to come up will be gone.”

“When depressed people try to meditate,” says Epstein, “a major part of their meditative energy is going into fighting depression. Instead of letting it take them forward, they are using their meditation as an attempt to self-medicate. The bulk of their energy may go into obsessive ruminations or attempts to process emotional pain that feels stuck. They are facing a gradient that is too steep.”

On the other hand, if depression reveals the charnel ground, couldn’t it be viewed as a gift? In his book, Martin writes movingly of the acute awareness of death, decay, and impermanence that was a major feature of his year-long depression. Although he ultimately found relief in an antidepressant, he notes that the bleak landscape of depression offers the Buddhist plenty of rich material. “I had a chance to see that joy is commitment to life and that it is different from mere satisfaction,” he tells me. “I had a better chance to see that because my pain was so intense. Some of the things we ordinarily do to bring happiness didn’t work anymore.”

And yet, if long-term meditators are known to experience dark nights of the soul or desert wastelands on the path, how is one to know if one’s suffering is from one of the warning signs of a debilitating illness or simply piercing the veils of illusion? Is the characteristic “hollowness” and “emptiness” of clinical depression altogether different from the experience of shunyata? By mistaking a glimpse of shunyata for a symptom of depression, might one risk medicating away the early stages of nirvana?

Engler, psychiatrist and Vipassana teacher, avers that the resemblance is only superficial. “In Vipassana meditation, the practice unfolds in a fairly recognizable way through seventeen classic stages of insight. There are two points—at stage three and stage eight – when the meditator experiences something like a depressive withdrawal from the world.

“It’s not like a clinical depression, though. It’s a natural reaction to seeing through the apparent satisfactoriness of things, a natural turning away from everything that isn’t ultimately satisfying. But it’s done with great clarity of mind and equanimity; it’s not like the hopelessness of depression, when you can’t stand outside it. Depressed people feel lifeless and unmotivated; often they cannot practice.”

Says Sylvia Boorstein, psychotherapist and Insight Meditation teacher with the Spirit Rock community in Marin County, California: “In order to see the emptiness and impermanence of all phenomena, you have to have enough energy in the mind to see clearly. When the mind is torpid you can’t see anything.”

Maybe, however, there is such a thing as too little dukkha, the unsatisfactoriness of life that is the premise of the Buddha’s First Noble Truth. “It was like the weather in California,” my friend “Annie”(another practitioner who requested anonymity) tells me of her three and a half years on Paxil. “Everything was always fine. I didn’t want to hear about anyone else’s problems; I thought everyone should just be happy—like me. Now that I’m off it I have my feelings back. Of course, I have to admit it got me out of my depression.”

This “flattened affect,” narrowed emotional range, or lack of depth, is a frequent complaint about the SSRIs; some people say they can’t cry at the world’s saddest movie, or they simply don’t feel like themselves anymore. Opponents of SSRIs accuse the drugs of making people into shallow, insensitive, back-slapping boors, impervious to subtle shades of emotion and intolerant of others. These qualities might be unsettling to anyone, but especially to those who have taken the Bodhisattva Vow, who cultivate the fundamental awareness of dukkha. Without embracing the First Noble Truth, Buddhism risks being one of those New Age light-and-love theologies, wherein everything is getting better and better all the time.

But is the California Effect really a fact of life on Prozac? Virtually all the mental health professionals I interviewed said no: Prozac is not supposed to transform soulful people into perky Stepford wives. When that occurs, it is properly considered an “adverse effect,” usually remedied fairly easily by either lowering the dosage or switching to another SSRI. “One woman I worked with told me that on Prozac she felt like Happy Girl,” says nurse specialist Morgan of Boston. “When she backed down on the dose her full range of emotion was restored.”

In some ways the dispute over antidepressants recalls discussions about “talking therapy” in the fifties and sixties. The analysts, who then ruled psychiatric departments – and who were supposed to perform miracles – remained aloof from the dirty work of medication, considering drug prescribing a breach of the sacred analytic relationship. In the same way, in Buddhist circles ten or twenty years ago, practice alone was supposed to be the antidote for all ills. “I think today we’re more mature than we were in the love-is-all-you-need seventies,” says Boorstein. “We have a more realistic idea of what a practice can and can’t do. It doesn’t transform the personality. If you were shy, you’re still going to be shy. If you have a short fuse, well, it might get a little better. But you’re not going to fly.”

There is a taboo around antidepressants among Baby Boomer Buddhists. (Three people interviewed here, for instance, chose to remain anonymous.) Often, the taboo reflects a lack of sophistication about brain science. In contrast to the longstanding (and flamboyant) association between Buddhism and the arts in America, science has not been a traditional Buddhist stomping ground – though there are signs that this is no longer true.

Another entrenched Buddhist taboo concerns a certain type of emotional self-involvement, the promulgation of one’s “personal story.” “A lot of Zen teachers think you should never talk about your emotions,” says John Tarrant of Sonoma County, California, roshi of the California Diamond Sangha and author of a recent book, The Light Inside the Dark: Zen, Soul and the Spiritual Life (HarperCollins). “That’s very common, the idea that they are a distraction.” Traditionally, Tibetan lamas, too, have been oblivious to a personal interpretation of psychological pain, according to Gelek Rinpoche of the Jewel Heart Dharma Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He himself used to have reservations about antidepressants until he saw how much some of his friends were helped by them. “Mental suffering is real suffering, sometimes more powerful than physical suffering,” he says. “I am talking about the suffering that is mentally and psychologically experienced by the individual, rather than universal suffering. The older generation will ignore it, but one should not ignore it or deny it.

“Teachings and practice can help you,” he adds, “but using dharma to affect a chemical balance is the long way round; it can be too late for some people. When there is a chemical imbalance in the body, it is a good idea to work with that chemically.”

Psychopharmacology is still an inexact science, yet rather than obscuring the true nature of mind, Prozac (or Prozac consciousness) may do just the opposite. Like mindfulness meditation, neuropharmacology, which deals with the action of drugs in the nervous system, reveals to us a mind that is not a fixed entity but an ever-flowing succession of states. Author Paul Fleischman of Amherst, Massachusetts, who is a psychiatrist and vipassana teacher in the tradition of S. N. Goenka, tells me that, “Buddha used the term asava, meaning flow. Our mental life is based upon flow, he said, and he meant specifically the flow of particles. Our body is composed of particles, and our thoughts and feelings are based on changes in the flow of these particles. He [Buddha] was meditating and he figured that out.”

A few decades ago, neuroscientists were dealing with a brain that was primarily neuroanatomical/mechanical, with neat contour maps of “centers” for speech, vision, language, rage, and so on; it might have been complicated, but with time and effort, neuroscientists felt, we could deconstruct the wiring and figure out which switchboardlike connections went where. The mind/brain was a thing, composed of hard, solid parts. A brief glimpse of modern neuropharmacology, however, plunges us into a microworld that is always in flux.

Not so long ago, there was one known serotonin receptor; then there were three; now there are new ones being discovered practically every day. The receptor molecule – often depicted inaccurately as a “lock” opened by the perfectly shaped “key” of the neurotransmitter—is not a hard, solid thing but a fluid shape-shifter; every time you throw a molecule of a drug (like Prozac) at it, it is changed. Under the influence of the ceaseless ebb and flow of a hundred-plus chemical transmitters (most of which are still unidentified), the mind is much more like a river—Heraclitus’s river, which is never the same river twice—than, say, a computer. When we meditate and watch our thoughts arise and die away, we may be actually observing the higher-level “readout” of fluctuations in concentrations of serotonin or norepinephrine or glutamate in the synapse, the opening and closing of minute ion channels, and so on.

Many psychiatrists who work with SSRIs think that, in ways that are still mysterious, the medication can “reset the thermostat,” reprogramming the mind to experience joy or ease. “Sometimes it can reset the setting,” says San Francisco psychiatrist Seymour Boorstein, “and the patient can go off Prozac.” My friend “Annie” says, “Paxil trained my mind to be happy. I learned the behaviors of a happy person and then after I went off the medication I could sustain that happiness because I had acquired a set of new behaviors like smiling, asking people about themselves, spending time with friends, and so on.”

There is nothing inherently antispiritual in this process. “What is serotonin?” asks Tarrant. “It, too, is a piece of the original light. For some people it comes in the form of serotonin; for others in the form of a smile. There is more than one way to move neurotransmitters around – meditation can do it; having someone hug you does it, too.”

Says Fleischman: “I feel emboldened to say that Vipassana meditation changes your neurotransmission.”

All of this leads to what may be the ultimate question: Can a depressed person be enlightened? Or—alternately—can an enlightened person be depressed? On this matter I found much difference of opinion.

“No,” says Fleischman unhesitatingly. “The goal—nibbana—is total purification, which means no negativity, no anger, no hatred, no sexual feeling, no upset, no depression, no rage. That’s the definition of a Buddha, someone who has attained that.”

But even to some practitioners this state of mind sounds suspiciously like the flat affect attributed to too much Prozac. We are all said to have the Buddha nature, yet the iconographic Buddha, austere and remote as those serenely beautiful Southeast Asian statues, does not seem like any relative of mine. Clearly, one’s view of enlightenment informs how one thinks about depression.

“When you experience the first kensho,” says Bodhin Kjolhede, abbot of the Rochester Zen Center in New York state, “this enlightenment experience does not clean up the basic afflictions. It does not eliminate greed and anger and emotional habits. Even when people have had fairly deep experiences of awakening, they still have tendencies or afflictions or habit energies with amazing staying power. But our relationship to them changes.

“Depression is one of those things. After enlightenment you can still be depressed, but it’s not as disruptive or frightening because you see it as transient and insubstantial, like all phenomena.”

A proverb for our times: Before enlightenment, take Prozac and talk to your shrink; after enlightenment, take Prozac and talk to your shrink. Perhaps it is only when we think the mind is something, that a mental state is something (paranoia or anxiety disorder, let’s say), that enlightenment itself is something, that we get into difficulty. “If you’re taking Zoloft,” says Tarrant, “what you do is to attend, to take notice. How much does it lift your depression? Does it stop your thinking from being clear? Does it reduce your passion for life? Does it make you a little bit manic?”

Just as it is naive to imagine meditation as a panacea for all psychological ills, perhaps it is a Western prejudice to insist that an enlightened master should be the picture of what we consider perfect mental health. Gelek Rinpoche tells a story about a very high lama in Tibet who suffered from a serious mental illness—probably bipolar illness or schizophrenia—and periodically behaved bizarrely. His mental illness did not seem to impair his spiritual status.

“The idea of complete psychological adjustment is foreign to the chaotic nature of life,” says Tarrant. “The possibility of reaching out into a deeper dimension is there even if we are psychologically unhappy. There is a movement within Buddhism that says, ‘There are all these hindrances to my achieving clarity. I need to detach from my desires and aversions so I can cease to suffer.’ A lot of people thought this was sort of boring—not true to life, not quite human—and along came Mahayana, and it said, ‘Right in the midst of what you see as the problems of life you’ll find your enlightenment.’”

Perhaps the Buddha was in the grips of a deep depression when he walked away from his castle and family to join the ragged sadhus, swinging bipolarly (a modern shrink might observe) between severe austerities and vertiginous indulgences. Would a psychiatrist armed with a DSM manual and a Hamilton rating scale have diagnosed depression or at least chronic dysthymic personality? Is it possible to see in Shakyamuni’s behavior hints of the warning signs in medical pamphlets—”Have you lost interest in life? Experienced changes in appetite or sleep patterns? Stopped socializing with friends?” Was Buddha the sixth century B.C.E. equivalent of the depressed housewife who refuses to get dressed, comb her hair, or cook a meal?

So determined was the thirty-five-year-old ex-prince that he finally sat down under a pipal tree one day near the city of Gaya in northern India, vowing not to get up, until he’d found the answer.

The Buddha did not have the Prozac option, of course, or even the psychotherapy option, so he invented something radically new. He didn’t just follow someone else’s program. Perhaps if he’d had Prozac, his drive to heal himself wouldn’t have been so urgent, and he might have been happy and gone back to his palace, and we wouldn’t have had Buddhism. Then again, maybe he wasn’t depressed as we know depression. Perhaps there was then—and always will be—a distinction between a spiritual crisis and a psychological crisis.