Secret Tibet

Fosco Maraini

The Harvill Press: London, 2001

425 pp.; $35 (cloth)

There is something about traveling in Tibet that makes Westerners reach for their pens. But of the literally dozens of travelers who have described their Tibetan adventures, few have possessed Fosco Maraini’s talent for writing. Maraini describing his bus journey across town would be enjoyable enough; to read his evocative account of traveling in Tibet is a real pleasure. His style, a blend of poetic speculation and careful observation, might well be described as “Herman Hesse meets Bruce Chatwin,” and like a great composer, he knows when to expand a theme and when to leave space for the listener’s own imagination.

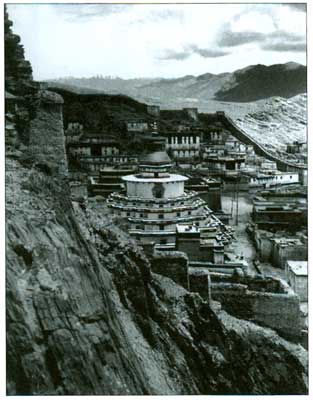

Maraini, an Anglo-Italian, Tibetan-speaking anthropologist, traveled in Tibet in 1937 and again in 1948. This book is a synthesis of the two expeditions made before the Communist Chinese takeover in 1949 irrevocably changed Tibetan society. In that bygone era, the journey from Europe began with a sea voyage to India, while Tibet was traversed only on foot or horseback. Although it was not the Forbidden Land of popular mythology, access to Tibet was strictly controlled by the Tibetans and the British Government of India, who cooperated to protect the Tibetan Buddhist system from both Chinese territorial ambitions and the onslaught of modernity. Few nonofficial visitors were permitted to cross the Indo-Tibetan border. But as an assistant to the great Italian Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci, Maraini was a privileged visitor, though even he was denied permission to accompany the “Buddhist” Professor Tucci as far as Lhasa.

Maraini’s Tibetan travels were actually fairly modest. He was only permitted to journey along the main trade route from British-controlled Sikkim to Gyantse (120 miles southwest of Lhasa), where a British outpost offered comparative comforts. But if this was the “main road” for European visitors to Tibet, none had studied the temples and monasteries along the route with the thoroughness of Tucci, and few were at home among the Tibetan people to the extent that Maraini was. His descriptions of his encounters with Tibetans are the most fascinating parts of this book, and bring to the fore his gift for relaying conversations. While he does outline the key features of Tibetan society, Maraini’s real concern is with people. “Who,” he asks, “can take an interest in abstraction when there are men of flesh and blood to get to know?”—and it is a rich pageant of characters that he meets.

The great joy of this work is that Tibetans are portrayed as individuals, not as occupations, classes or tribal groups. This is a portrait, not of textual ideals or of Shangri-La, but of Tibetan life as it was lived in all its beauty and ugliness. As Maraini’s Tibetan muse, the Princess Pema tells him:

We are so different from what people imagine us to be, you know… Often when I read books about us by foreigners, I think that they don’t understand us at all. A country of saints and ascetics who care nothing for the world, indeed! Ah! You must read the life of Milarepa if you want to understand us. Greed, magic spells, passion, revenge, crimes, love, envy, torture. . . . Besides, what need would there be to preach the [Buddhist] law to us so much if we were always good and full of virtue?

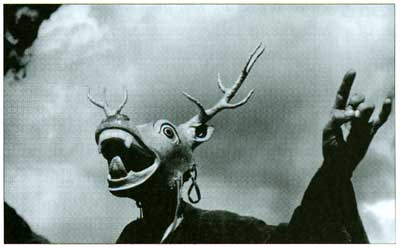

Maraini tries to translate culture rather than to represent it on its own terms. He seeks “the common essence of all mankind” and attempts to locate Indo-Tibetan culture within the great cultures of the world. But for Maraini—as for the present Dalai Lama—“studying the East and loving it does not involve conversion to it and renouncing one’s own civilization.” Thus he is able to celebrate his own culture (“the invisible cathedrals of Mozart, Vivaldi, Beethoven”) as well as that of Buddhist Tibet. The result is sometimes essentialist as he lingers over the baroque and the sensual,but it is ultimately a sympathetic portrait of a Buddhist society that produced “a serene and happy nation.”

Along with the Princess Pema, one figure recurs throughout the narrative. The leader of Maraini’s party, Professor Tucci, is one of the great names of Tibetan studies, a polymath whose knowledge of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism was then unrivaled, a man who could, and did, compare the art and culture of a dozen Asian civilizations. Maraini paints an unforgettable portrait of Tucci, a man of restless energy and constantly enquiring mind “with something of the shaman about him” and “a brain in which entire libraries lie in ambush.” But Tucci was a complex and opportunistic character, a grand professor who expected his traveling companions to address him as “Your Excellency” even over the campfire! There was, the author observes, “something of the night in Tucci, something feline, Tantric, not to say sinister.” All that obstructed his work was to be swept aside, and to attain this Tucci flattered the powerful, whether Tibetan incarnations, imperial officials, or fascist dictators. He was, Maraini seems to reluctantly conclude, ultimately an opportunist, but one who left “precisely what he wold have wanted to remain—his work.

Secret Tibet was first published in Italian in 1951 and appeared in English the following year. While the original English edition occasionally turns up in secondhand bookshops, this revised, augmented edition is a welcome reprint. Lavishly illustrated with many more photos than the original contained, it has been updated to include Maraini’s comments on the Chinese Communist occupation and its destruction of Tibet’s cultural heritage. These are included in a “Reconsideration” at the end of each chapter. As is true of the glossary, the eclectic bibliography, and the concluding chapters on the history and culture of Tibet, there is little here that is new and much that is now dated. But the traditional Buddhist history of Tibet has seldom been better told for the Western reader. There is a wonderfully readable account of the legend of Milarepa, that most human of Tibetan “saints,” an archetypical religious ascetic whose spiritual journey led him from black magic to ultimate illumination in his mountain fastness. Unfortunately, the account of Tibet’s Bon religion as a primitive animist-shamanist faith is seriously dated and does not reflect the Bonpo’s own understanding of their faith. But Maraini’s critique of Bon, that “no great human spirit has expressed himself in it—a sure sign of inferiority” must be addressed by the Bonpo themselves.

What, then, is the secret of Tibet? It won’t spoil the reader’s enjoyment to know in advance that Maraini’s “secret” is that Tibet is normal and full of real people, made of flesh and blood.