An artist and a student of Buddhism, Leidy Churchman was born in 1979 in Villanova, Pennsylvania, and lives and works in New York City and Maine. Churchman’s most recent solo exhibition opened in February at Matthew Marks Gallery in New York; a survey of the artist’s films, paintings, and ceramics was held at the Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, in 2019. Churchman (who uses the pronouns they/them) spoke to Tricycle from their Maine studio about the relationship between their painting and their Buddhist practice.

Anne Doran: Knowing a bit about you and your art, it doesn’t seem to me as though becoming a student of Buddhism would have been a big leap for you. But I’m wondering at what point you started taking a serious interest in it. Leidy Churchman: It’s a bit difficult to peel back the layers and find that moment. It’s the same with art. The more years go by, the harder it is to remember why I even became an artist.

That was going to be my second question. I do think that finding a place in yourself where you might start an art practice and finding a place in yourself where you might start a Buddhist practice are similar. Just now, I’m rereading Chögyam Trungpa’s Dharma Art again.

That book is a bit cryptic, because Trungpa points at things rather than spelling them out. Which can be frustrating because you’re always chasing after him, and he is relentless! But after reading it a lot of times, I think Trungpa’s pointing at that place of practice and how we understand ultimate and relative symbology. I started making art because I realized that that was where I could bring things to think about and work on—and be surprised. I could bring life there and work with it in a way that I couldn’t do anywhere else.

And so, when I think about the art I made before I was studying Buddhism, it’s not like there isn’t dharma there. It’s not like my art has changed; it’s still a container that I put what I’m thinking about into, see what it looks like in there, and watch it in a space outside of normal life. I think Buddhism functions in that way as well.

Whom do you study with? I don’t have a main teacher right now. I’ve been pen pals with Reverend angel Kyodo williams for a few years now, and recently I’ve been attending her online teachings. I have spent a lot of time with my Buddhist mentor Gayle Hanson. We practice together. I was going to Shambhala for a while. I’ve been looking for a teacher for a long time, but I’ve learned it’s not so easy to find one.

“It’s important to take risks. If it feels like the right thing to paint at the time, I’ll just go for it.”

Gayle and I do a family-style Zoom class together. We’ve gone back to basics. Gayle was only going to teach me, and then a bunch of my friends said they wanted to do it too. It wouldn’t have happened except for the pandemic. I have taken a class on mahamudra [an advanced Tibetan Buddhist meditation] at Nitartha Institute, and I plan to attend Ponlop Rinpoche’s Summer Institute, which this year will be online.

They say you find your teacher when you’re supposed to find your teacher and you find your sangha when you’re supposed to find your sangha. I would love to practice somewhere in person with a great teacher and a cool sangha, but how people connect to the dharma was changing even before this pandemic, with new teachers and communities and new ways to find them.

I think that we will go back to going on retreats and things like that. But maybe online teachings will be a permanent part of how the dharma gets transmitted.

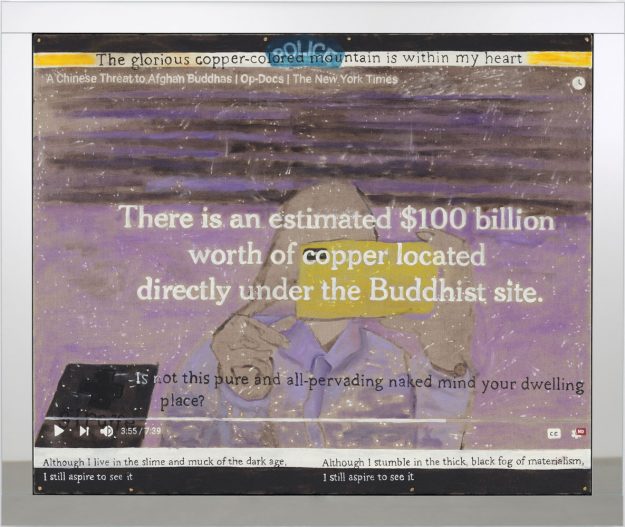

I see in your art that you are interested in depicting lots of different things. And, as you say, it is a bucket into which you can pour all those things. Now, obviously, that includes your Buddhist practice—just as your Buddhism bucket, I presume, will hold your art. But I have to say I don’t see a huge difference between the art you were making before you started studying the dharma and the art you make now, in terms of specifically Buddhist content. That’s because I think that it is clichéd to make art about Buddhism or the Buddha. I remember at one point I was like, Oh my God, is that what I’m doing? But it’s also important to take risks. If it feels like the right thing to paint at the time, I’ll just go for it.

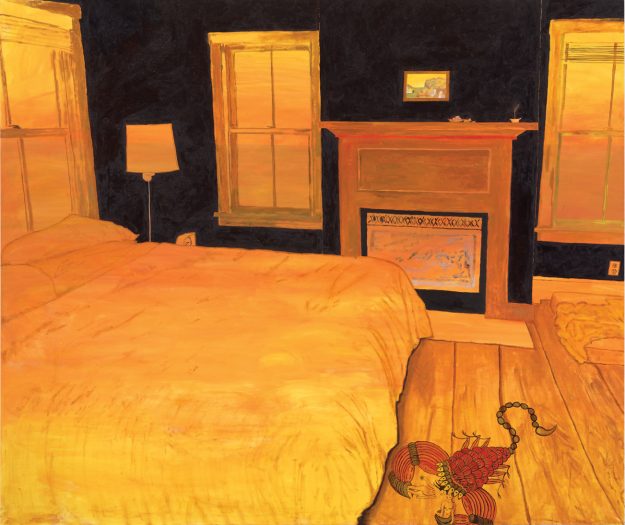

I like that about your art. I like that you can do a painting of a buddha and you can do a painting like the one I was just looking at of a chest of drawers and a snake titled Ourobureau, which made me laugh. You can produce a work that seems quite devotional like your painting Reclining Buddha and then one that incorporates this rather terrible pun. Yeah, I think that the range comes from making paintings in groups altogether at one time, or over time together. I don’t tend to paint variations on a theme or subject, or work in series. In a way, I could be painting anything. I was just reading an article by the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso about perception. He says that first you see. Then you look. And then you start to comingle with the thing you’re looking at. The thing you’re looking at starts doing its thing, and then you just merge with it. I think that’s what happens, in a way, when I paint something. I have a kind of certainty that this is something I can paint. And then you have this ongoing exchange with the thing you are painting where you are watching what it’s doing and then you are doing something and you’re having a back-and-forth.

I get the impression that you are never trying to produce an iconographic image, an “important” image, which stands on its own. I once did a painting of a Tibetan rug that was in the “Rugs and Ritual in Tibetan Buddhism” exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2010–2011. And I chose that particular rug because it was the one on the poster for the show. So I do sometimes pick a popular image over one that’s more obscure.

But you’re right—I do feel free to make a painting of something really odd, because the last one was of the Mastercard logo or a Pepsi machine. I’m always trying to start from a different place and see what happens. A lot of it is holding back and seeing what the painting is doing on its own. I love how painting can be so ordinary, too. Yeah, there’s definitely no part of me that wants to show you my skill, or my big idea.

Your work certainly always seems to me to be more in the nature of an investigation. I’ve been thinking a lot about the pandemic, but if I just made one painting about it, it would be so dead on arrival. I want my paintings to be free not to stand in for a universal truth. So if you see one on its own, there’s a lot that’s not being said but that’s OK.

Speaking of the pandemic, I see that the world, and especially America, is being taught a big lesson in interdependence by the coronavirus. And I also see a lot of pushback against that lesson. I saw a placard on the news the other night that read “selfish and proud of it.” Well, reality has changed. I can’t really talk about the politics of it. I just think that everybody’s egos have been hit hard. There is a gap, which feels like boredom, that I think is interesting.

I’m interested in why you find that interesting. Because things have been taken away. For instance, mental projections about the future have hit a dead end. I’m interested in how that has moved us into a quite raw and spacious moment where the future isn’t yet known. I’m recognizing that even for someone like me, who doesn’t mind being alone for long periods of time, isolating is hard. But then something opens up, and that claustrophobia actually becomes space again.

I’d like to ask about your interest in teachers like Reverend angel Kyodo williams and Lama Rod Owens, who are both queer people of color. They are both exceptional teachers who are expanding the context for receiving the dharma. They are promoting change. At Shambhala I could see how everybody was preserving a certain institutional structure. If somebody asked me where they should study painting right now, I would think about the teachers that would be good for them, not the institutions. I wouldn’t put my trust in any institution right now. Or not in the way one might have before. The question for me is where you want to go with the dharma. What is it that you want from the sangha?

“A lot of it is holding back and seeing what the painting is doing on its own.”So it isn’t only about what teacher might be good for someone but also about who they are catering to. Who are they making sure to include? Racial injustice in this country is pervasive. And that is where the dharma can actually go. If people are rooted in a dharma practice and connected to a sangha, then they can study who they really are and who they are not. They can contemplate what conditions have affected how they know and see themselves, and how, with the help of a sangha, they can take that apart.

There is a book out now called Buddhism and Whiteness: Critical Reflections (Lexington Books, 2019) that really feels like a follow-up to Radical Dharma (North Atlantic Books, 2016). It’s a real recognition of what has to happen if Buddhism is going to be a means to liberate oneself in America.

For me, on a very personal level, practicing meditation, learning dharma, is a way to go beyond my best ideas, to be with my mind, and to further dissolve the conditioning that I have been subject to, as well as the conditioning I’ve not even noticed yet.

That sounds to me a lot like how one finds one’s way as an artist. Yeah. Things happen so subtly. Maybe somebody you admire comes to your studio to see your work. And they can point out things you might not have seen in it yourself. Because you are blind. You can’t see what you’re doing. Maybe the dharma’s something like that.