In January of 2000, Ugyen Trinley Dorje, the fifteen-year-old head of the Karma-Kagyu lineage, engineered a daring escape from Chinese-controlled Tibet. Two years later, a determined journalist manages to interview him.

Delhi, September 8, 2001

It’s dusk in Delhi. I stand with a group of excited women, the outsider at a gathering of friends. Drawn by the scent of a good story, I am here to try to interview His Holiness the seventeenth Gyalwa Karmapa.

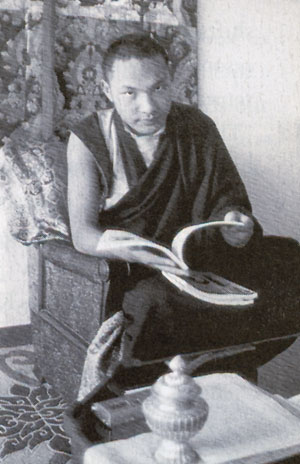

My hasty preparation for the anticipated interview has thrown up a host of facts—sectarian conflicts threatening the fragile Tibetan community struggling to survive in exile; the two rival Karmapas supported by a slew of prominent Karma Kagyu Rinpoches; Ugyen Trinley Dorje’s dramatic flight from Tibet in early 2000; and the Dalai Lama’s recognition of him as the Karmapa, which has granted the seventeen-year-old a measure of legitimacy. And yet, the Karmapa’s throne at Rumtek lies vacant.

Blaring sirens pierce my reverie. He’s here! The women around me hastily light the clay diyas(oil lamps) in a traditional Indian gesture of welcome. Escort cars screech to a halt. And then—confusion. Burly gun-toting guards push everyone aside as a lanky, young maroon-robed monk steps out. It’s dark. In the light of the flickering diyas, I catch a glimpse of a fresh-faced youth, tired but composed. He is quickly hustled inside. The throng follows. I watch as the diyas flicker out, then turn to go within.

Inside, everyone’s being lined up for what Hindus would call darshan—a glimpse of a holy person within the temple’s sanctum sanctorum, an interface between the sacred and the profane. Who knows what might happen? I dutifully take a kata (ritual scarf) and fall in line, ready to be blessed.

My turn comes. I step into a room that seems a blur of brown, except for that figure seated before me. Vibrant in maroon, he rises. Our eyes meet. Everything—the clamor within and without, the many presences and voices, past, present, future—shifts ever so subtly and becomes still. A momentary resonance within me of something wise and beautiful, a reminder of my own innate Buddhahood? He whispers, “Thank you,” in English as he places the kata I’ve offered him around my neck. It is customary to present a kata to lamas as a mark of respect, which they then give back, symbolic of their blessing.

“Sorry, no interview possible here,” I am told in no uncertain terms by the Karmapa’s security. Better to meet the Karmapa at home, I think. Or the closest he has to home right now—the Gyuto Ramoche Monastery in Sidhbari, near Dharamsala.

Sidhbari, October 31 – November 1, 2001

Two months later, under a full moon, I set off, in search of the elusive Karmapa and his wisdom. It is an overnight train journey from Delhi to Pathankot, and then a three-hour drive to Sidhbari, for which there are no direct trains. I take a cab from Pathankot station. Midway, I stop at a roadside restaurant for tea, and quite serendipitously discover a cave where Tilopa, founder of the Karmapa’s Karma Kagyu lineage, is said to have spent long years in retreat. I am immediately reminded of the legend of a cave somewhere in the mountains of north India where Tilopa kept himself chained for twelve years in meditation, until one day, all chains, mental and tangible, fell away.

Is this it? A stream flows into a waterfall nearby. Until a few years ago, one could actually sit here and meditate, a fellow traveler informs me. Then one of the 330 million Hindu deities took over, and Tilopa’s cave became just another one of the countless shrines that dot India. I sound the metal bell at the shrine, and come away a dispirited tinkle later. That seems to set the tone for the rest of that day. The Karmapa cannot be photographed without a permit from the office of the Superintendent of Police, I was told when the interview was granted. I have reached my destination a day early, but all offices are closed to celebrate Valmiki Jayanti, the birthday of the sage-composer of the Hindu epic Ramayana. I spend the rest of the day rushing through the narrow lanes of this hill-town, from one official to another in search of the permit.

By the time the Superintendent of Police signs the permit, it is dusk in Dharamsala. Hassled and drained, I return to the Norbulingka guesthouse, set in a valley ringed by the majestic Dhauladhar range. As I trudge back to my room, my mind in a flux, a giggling Tibetan child appears before me. For a second, I think the little boy is a vision—he actually seems luminous to my tired eyes. A guesthouse attendant tells me that the child’s parents have sent him from Tibet in the hope of a better future in India. As the little boy’s laughter echoes in the near-empty guesthouse, I think of the young Karmapa. The image of a smiling little boy floats before my eyes, a boy whose sisters called him Apo Gaga, Tibetan for “happy brother.” He’s been separated from them twice—once when he was recognized as an incarnate lama, and then when, in January 2000, he secretly left his monastery in Tsurphu, Tibet, and made it on foot to India.

What a journey it has been for the erstwhile Apo Gaga, from the nomadic life of his parents in remote Lhathok province, to the Chinese-controlled enthronement at Tsurphu, to a far-from-certain life in India. For the succession controversy still casts its shadow, and there have been rumors in the Indian media that the Karmapa is a Chinese spy. It’s a brilliant moonlit night in Sidhbari. Yet I discern some clouds gathering on the horizon.

November 2, 2001

Gyuto Ramoche Monastery. A stark, four-story structure ringed with a stretch of unkempt grass. A lone khaki-clad guard stands next to a ramshackle tin hut. I expect him to stop me, but he doesn’t. A little further away, a policewoman does, and leads me to a waiting area. Sunlight streaming in relieves the bareness of the “waiting room” somewhat. So do the maroon-robed monks and nuns milling around, chattering in Tibetan. I am motioned to one of the few plastic chairs in the room. A monk sitting nearby asks me in broken English: “You meet Karmapa?” I smile: “Yes, I am here to interview him.” The policewoman is back, with a couple of her colleagues in mufti. All regard me with great amusement. My “permit” is demanded and appropriated, and I am asked to enter my particulars in an official-looking register. Address, age, sex, organization. “You’ve come from Delhi to interview the Karmapa? What will you talk about?” asks the policewoman incredulously. “God knows what’s all the fuss about this Tibbati (Hindi for “Tibetan”). He doesn’t even know English, or Hindi for that matter.”

It appears that those who “guard” the Karmapa have little idea of his prominence in the Buddhist world, and no reverence for his spiritual wisdom. It is almost eleven o’clock, the slot I have been given for the interview. A Buddhist woman from Costa Rica, who has listened in on my interactions with the security, points to the crowd of monks and nuns and says, “All these people have been given the same time to meet him, and so have I!” The policewoman retorts, “Be thankful your appointments were not canceled. He is not well, and we are not letting many people meet him.”

I feel small in the presence of so many seeking him within this small window of time: a group of tiny old Tibetan women bedecked in jade; a newborn baby; an older child. Young nuns from Rumtek. A Taiwanese woman; the Costa Rican woman. A few precious moments bear the faith of so many. My impatience melts, and I await my moment with the Karmapa. Clock hands move forward, time stands still.

The Karmapa begins his day early, I am told. The morning is devoted to study with his teacher Thrangu Rinpoche. He is allowed to give personal blessings for an hour between 11 and 12. The policewoman tells me that I must finish by noon as that is when His Holiness is taken for lunch. Public discourses are at 2 p.m. but apparently are often arbitrarily canceled.

Suddenly there’s a commotion. Men are asked to move to another room. Policewomen position themselves at one end. All women are to be frisked, I assume for weapons. It is ironical to see nuns, not allowed any possessions according to sangha rules, submitting cheerfully to a search for hidden weapons. For all the hullabaloo, the search is cursory. An irritating formality for the security personnel, to be gotten through as soon as possible. The Karmapa’s in a prison which is easy to protect, but difficult to escape.

The policewoman calls out, “Let these people finish first. You can wait upstairs. Follow me.”

The wheel’s finally turning.

I follow the policewoman’s blue figure through large, empty rooms and endless corridors. In one deserted room, cabbages and carrots lie on long wooden tables waiting to be cooked. Ahead, the monks and nuns are walking in a single file up a flight of stairs. We ascend, one floor after another, in silence. There’s a policeman at every landing, AK-47 at the ready. The feeling of being in a prison grows. A question arises that I could never ask the Karmapa: How do you feel living like this, almost as a prisoner? Didn’t you leave behind your land and monastery in search of freedom? But I have been forewarned against asking “political questions.” And, as I am soon to find out, representatives of the Indian Intelligence Bureau, the MEA (Ministry for External Affairs), and the local police will sit in on the interview to make sure I don’t.

A pause one floor below the Karmapa’s quarters. “You wait here while I take these people inside,” says the policewoman to me. She and her colleagues are the ones who are obviously in charge of the Karmapa’s time, and whom he meets and doesn’t. A young nun writing laboriously in a notebook is pointed out to me. It is Ngodrup Palzom, the Karmapa’s sister. Palzom is learning English. Smiling, she reads out from her book, whose pages she has filled with her beautiful cursive handwriting: “I look like my mother.” It makes me think of the families torn apart by conflict all over the world. Like the Karmapa’s. And of the little boy in the guesthouse.

Tense moments follow. I look out the window at what the Karmapa must see whenever he looks out of his room upstairs. Structures. A lot of blue sky dotted with prayer flags. The Dhauladhars far away. But nearer than Tibet, nearer than home. “Come,” says my policewoman. It is 11:30.

A large, sun-filled room. A sea of maroon carpeting at the end of which the Karmapa is seated. Big windows toward the left. An altar with a glass-encased Buddha to the right. The Karmapa rises and places a red ceremonial ribbon in my hands. It slips from my open palms, but His Holiness catches it before it falls down. “Sorry,” he smiles and accepts the few offerings I have brought. Tenam Shastri, a monk in the Karmapa’s entourage, has agreed to translate. I sit facing the Karmapa, the translator to my left. I switch on my dictaphone and we are ready to begin.

“Do you share a special relationship with birds?” With this question, I want to establish a link between the present Karmapa and his predecessor, whose fondness for birds is legendary among those who knew him well. Perhaps I am also looking for an insight into how reincarnation works. I examine the Karmapa’s face for any sign of surprise as this somewhat strange question is translated to him. I find none.

“I don’t know about ‘special,’ but birds are sentient beings and in that sense, I do have kinship with them,” he says. “But when people put them in cages for their own pleasure, it pains me as I feel all sentient beings have the right to their freedom.”

The young man’s spirit shines through. To me, he seems quite his own person, with his own views. His response also makes me think that perhaps what reincarnates, in the case of realized beings, is their wisdom, and not the personal characteristics of a particular birth.

Suddenly, “What is that? You have no permission to record this interview.” A rude interruption. A security person keeping an eye on us decides that I cannot use the dictaphone without specific permission. It is confiscated. I protest, close to tears. It’s all over, I think, my mind whirling.

And then I turn and look at the Karmapa, perhaps hoping for support. All the while, he has been sitting calmly, turning the pages of the issue of Tricycle I have given him. He looks up. An open, unafraid glance at the troublemaker, a calm understanding.

As the commotion continues, there emanates from him what I can only describe as a profound stillness. He seems to be simply observing all that’s happening around him. The disturbances, no more than ripples on water, arise and gently taper away. Indeed, the glass table between us divides a still mind from a very shaken one! I take out my pen and notepad and decide to write.

Explaining my first question, I say, “The reason I ask this question is that your predecessor, His Holiness the sixteenth Karmapa, had a special relationship with birds.” He replies: “His Holiness the sixteenth Karmapa was a great Mahabodhisattva, and each of his actions was for the benefit of all sentient beings. He did have a collection of birds, which he probably kept to liberate them from suffering. We cannot compare to what the great masters do. As far as I am concerned, I think that birds are essentially free and you and I cannot possibly know what they need! So it is best to let them be as they are, naturally.”

Again the passionate plea for freedom, and the recognition of the sacredness of all life. I move on to war and peace. Newspapers report conflicts erupting all over the world. Television screens show pain, anger, violence, tears, hatred. Tales of grasping minds, restless minds, controlled by afflictive emotions. Suffering.

What is the Buddhist solution to this crisis? The Karmapa looks thoughtful and answers, “To try and bring peace in the world, I believe that whether one is a Buddhist or not is immaterial. Irrespective of religion and nationality, every individual in the world must practice the dharma. And dharma practice not for your own self, but for the benefit of every sentient being in the universe. For as long as we can, each one of us must do this, for lasting harmony and peace in the world.

“As for there being a ‘Buddhist solution,’ I think that the world is huge, and if some issue is a ‘world issue,’ it is a vast issue too. So it is the case with this war and the present world situation. No one religion can hope to provide ready solutions. All the religions of the world need to cooperate to find lasting solutions to such problems, which I think will come about if everybody practices compassion, nonviolence and lovingkindness.” He has been facing a lot of problems of his own. Doesn’t he ever feel frustrated or disappointed? How does he deal with these feelings?

“The problems you refer to have been minor,” he says, and again I am struck by a sense of his quiet strength. “I do not feel them to be personal at all, although they have brought a lot of difficulties to my people and those who believe in me and are dedicated to me. As far as dealing with these is concerned, as a religious person, I pray and dedicate my merits so that these problems are resolved. Personally, I try and do everything as peacefully and truthfully as possible.”

But what about the succession controversy?

“There’s nothing to say,” he quietly replies. To an inquiry about moving to Rumtek, he says: “Not as yet. There is hope, but no decisions have been taken. So I cannot comment on that as of now. Of course, Rumtek is the seat of the Karmapa, and we have put in the request to the Indian government to be able to shift there. Whether I will be allowed to go there or not I do not know.”

I feel the uncertainty surrounding him, and his underlying optimism.

Some restrictions on his movements were lifted when he was recently allowed to visit Buddhist sacred places in India. “As a Buddhist monk, it was a great privilege to have been able to honor and pay my respects at the places connected with the Buddha Shakyamuni. And this pilgrimage is also important to me as a dharma practitioner. I enjoyed it very much and felt many blessings at the holy places.”

I now move on to questions about his life as a teenager. Has he ever felt a conflict between his identities as a monk and an adolescent? He speaks, his hands assuming a meditation posture, which I see often during the interview, “I am now seventeen years old. When I compare my past seventeen years with the lives of my predecessors, I realize I haven’t managed to do very much to benefit people or my lineage. But I have great hope that in future I will be able to follow in the footsteps of my predecessors and emulate their example.” He has not answered my question.

“But, Your Holiness,” I pursue, “most people your age have abundant physical energy, which is often expended through games and exercise. What do you do to keep fit?” “I was born in a remote area of Tibet, so there were not many toys or games to play at in my early childhood. Then, ever since I was recognized as the Karmapa, there have been a lot of responsibilities that I have to take care of. I also have my studies and have to contemplate many things. Everything has to be accorded appropriate time, so there is not much time to spare. But yes, as and when I get time, I do exercise.”

“Really! What sort of exercise?”

“I run.”

Where in the world does he run? I wonder. Not in this stark building. Not with his posse of policemen.

He has been receiving the rigorous training in religion and philosophy expected of the head of the Karma Kagyu sect. “Buddhist philosophy is the main subject that I focus on,” says the Karmapa. “Then there is Tibetan grammar, poetry, study of rituals, and also painting, art, astrology. Then, I also try and create music sometimes.” Ah! This is unexpected. Music?

“Although I am not studying music formally, I am interested in playing some musical instruments. One of the things I like doing is composing tunes on the flute.”

I imagine this beautiful young monk framed by the mountains playing his flute. “You’ve also been writing poetry. What sort of poetry is it, and what inspires you to compose it?”

“Actually, most traditional Tibetan poems are based on the poems of India, particularly one text written by an Indian master, Dandi. When I write a poem, it generally has a spiritual theme and context. Nature is a powerful inspiration for me, as is the nature of human beings.”

“Is there any hope that your poetry might be published?”

“Yes, in future.”

I think of Palzom, the Karmapa’s sister. “Have you been learning English, too?” I ask. “So far I haven’t, but I definitely want to. This will benefit not only me but other beings as well, as most communication in today’s world is in English.” Does this stem from a desire to communicate directly with a much wider audience than the Tibetan community? “Yes.” I have heard of his dreams, intuitive dreams. That they are painted as thangkas. Some by him, some by a thangka painter from Nepal. I ask him about these dream paintings.

“Everyone dreams,” he begins with characteristic humility. “As a human being, I, too, dream. And not every dream is significant. But sometimes in my dreams, some significant things emerge. In fact, many of my predecessors also dreamt of significant happenings, and had premonitions of future events through dreams. Because of their inherent importance, these dreams were painted. I try to follow the same tradition. Since these dreams and the paintings are too detailed, I don’t think I can tell you about it right now. If there is any element of truth in what I have dreamt, then there are certain things in my dreams related to the future of Tibet, and the future of the world.”

I want to know if I can see these paintings, see what he dreams. “Not now,” says Tenam Shastri.

Oddly, a cuckoo clock alerts us to the time.

The magic hour. Noon. The time when the Karmapa must go for his lunch. I look at him. He is waiting patiently for the next question.

“I am not sure whether one can ask an incarnate lama this, but I would like to. What are the stages of spiritual development that you have undergone in this lifetime?”

“In general,” he begins, “the Buddha-dharma may be preserved in two ways—through study, and through meditation practices. In my lineage, the path of meditation practice is emphasized. Presently that is what I am engaged in, and I hope to be able to continue and preserve the teachings and practices of my lineage.”

Another interruption. I am told to end the interview. Hoping that the question doesn’t sound too “political” (the security personnel have been there all along, visible out of the corner of my eye), I ask him about the Tibetan freedom struggle. “Young Tibetans are looking up to you as a future beacon of hope. What role do you visualize for yourself in the Tibetan freedom struggle?”

“As a Tibetan, I will do whatever I can to help in the freedom struggle. I have nothing specific to say at this point about what that will be. Since His Holiness the Dalai Lama, our spiritual and temporal leader, has led us to the path of nonviolence, I can say that I will follow that. His activities around the world have been based on this vision of a peaceful struggle. As for myself, I will work in accordance with the Dalai Lama’s wish and support his every endeavor.”

The security is getting impatient. I have overstayed. I sneak in a last question.

A message for the readers of Tricycle?

“Among all my predecessors, it was the sixteenth Karmapa who visited the United States. It is because of his Buddha activity that people in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world know the Karmapa. As his reincarnation, I respect and rejoice in his Buddha activity.

“As an incarnation of him, I have sincere prayers and dedication toward the whole world and that all sentient beings have peace and harmony. Specifically, the U.S. has had to face terrible tragedy at this time. Since September 11, it has been my prayer that this sort of event, in which lives are lost and people hurt, not happen again in future anywhere in the world. My wish is that every human being live in peace. And whatever conflict there is between countries might be resolved to the benefit of all, without war.”

“Are there any plans to visit and teach in the U.S. in the near future?”

“Yes, the plan is there, but not yet the reality. There is always hope.”

He waits for me to gather up my mess and walks me halfway to the door. The security takes over from there.

It is night in Dharamsala. The sky’s cloudy. Every now and then, a cloud obscures the moon. But only for a short while; the moon always shines through.

In spite of the interruptions., in spite of everything, so, too, will the Karmapa. One day, all chains will fall away. ▼