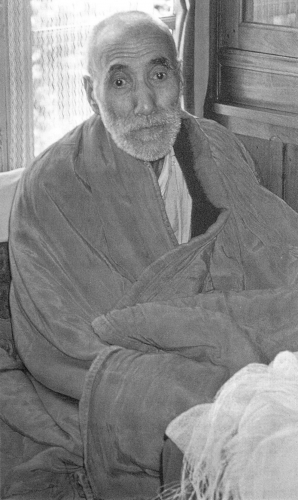

Khunu Rinpoche Tendzin Gyaltsen has been called a bodhisattva and saint by those who knew him. His knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism was so superior that he came to be accepted by lamas of different schools as one of the greatest Tibetan lamas of his time. Yet he was not ethnically Tibetan and was known as the “Precious One from Kinnaur,” referring to his birthplace in northern India.

Throughout his life from 1895 to 1977, Khunu Rinpoche taught and studied with some of the masters of the twentieth century as he traveled through India, Tibet, Nepal, and Sikkim—Sanskrit pandits in Benares, Hindu scholars in Varanasi, Tibetan lamas in Sikkim, Tibetan philosophy scholars at Sera Monastery in Lhasa. His concerns, interests, and impact transcended sectarian, political, linguistic, and national borders.

Shortly after his exile from Tibet, the Dalai Lama asked Khunu Rinpoche to teach the more learned of the refugee lamas in Mussoorie. His Holiness requested personal instruction from him on Shantideva’s Bodhicharyavatara (Entering the Path of Enlightenment), the great eighth-century guide for a bodhisattva. He also received the pointing-out instruction on the nature of mind known as the “Three Worlds Which Strike the Vital Points” from Khunu Rinpoche. The Dalai Lama’s respect for him was profound: He would prostrate to Rinpoche in the dust when they met at the Great Stupa in Bodh Gaya, the site of the Budhha’s enlightenment in India.

While never ordained as a monk, Khunu Rinpoche achieved an extraordinary degree of realization by observing the Bodhisattva vows. Focusing every action and thought upon the intent of enlightenment for all sentient creatures, he lived the life of a wandering yogi with a devoted female companion, the Drikung Khandro. Nor was he a prolific writer, but his lifelong devotion and study culminated in his single masterpiece, Vast as the Heavens, Deep as the Sea: Verses in Praise of Bodhicitta (Wisdom Publications, 1999). Written in 1959, it is Khunu Rinpoche’s account of a single year’s reflections on bodhicitta, the altruistic aspiration for enlightenment. The text is comprised of 356 four-line verses written in a blank diary, and their spirit and wisdom echoes Shantideva’s masterpiece, Bodhicaryavatara.

Some verses are as relevant for the world today as they were in 1959. For example:

With bodhicitta one sees self-interest

as being like a virulent poison.

With bodhicitta one sees altruism

as being like ambrosia.

The paradox of bodhicitta is described below:

If one throws precious bodhicitta away,

even if one seems to do something for the sake of others,

it will only apparently be so. A tree that does not bear fruit

may look good, but it cannot assuage hunger.

In Khunu Rinpoche’s original diary, he recorded the events of the day beneath each verse. In 1959 when His Holiness fled Tibet and arrived in India with 100,000 of his people, Khunu Rinpoche wrote of the anxiety he felt for their safety: “The newspapers are saying that fighting has died down in Lhasa. The Chinese are saying that His Holiness has fled. Some reports say he is probably making for Sikkim or Assam. Others say Lhokha. It seems the fighting is going on all around him.”

During the late sixties and seventies many young Westerners encountered Khunu Rinpoche in Benares. His renunciation and simplicity of life were well known, and numerous stories remain of his giving funds and foods to these students and world travelers when they visited him. An American, Tubten Pemo, met him in the mid-1970s in Kathmandu. She and others had gone to Nepal to study Buddhism, and she recalls that when they asked Rinpoche if there were anything he needed that they could supply, he answered, “No, I have all I need because I have bodhicitta.” The next day, he sent an offering of one rupee to each of the foreign students.

If you possess the wealth of bodhicitta

it doesn’t matter if you are attractive or not,

it doesn’t matter if you lack fame and honor,

it doesn’t matter if you have no other virtue.

THE POWER OF BODHICITTA

Since a buddha is born from a bodhisattva

and a bodhisattva is born from bodhicitta,

intelligent persons understand

the greatness of supreme

—

One who is of infinite benefit to wandering living beings,

who brings relief from suffering

and its causes through unsurpassed

bodhicitta, is a seedling buddha.

—

A boat delivers one to the other bank.

A needle stitches up one’s clothes.

A horse takes one where one wants to go.

Bodhicitta brings one to buddhahood.

—

With bodhicitta one enjoys happiness.

With bodhicitta one enjoys even sorrow.

With bodhicitta one enjoys what is there.

With bodhicitta one enjoys even what is not there.

—

Knowledge that reaches to the limits of the knowable,

love that extends to every living being,

and power that is like lightning:

these have their origin in bodhicitta.

—

Who could measure the heavens with a ruler?

Who could measure out the ocean with a cup?

Who could analyze the workings of karma with their mind?

Who could give voice to the greatness of bodhicitta?

—

For raising your spirits when you are down,

for removing arrogance when you are flush,

nothing in the world compares with the

non-deceiving friend that is bodhicitta.

—

This bodhicitta that serves as a sword

to cut the shoots of the afflictions

is the weapon for the protection

of all wandering beings.

THE PRACTICE OF BODHICITTA

If one investigates to find the supreme method

for accomplishing the aims of oneself and others,

it comes down to bodhicitta alone.

Being certain of this, develop it with joy.

—

In the morning when you get up, generate

a heartfelt intention to be in accord with bodhicitta.

In the evening when going to bed, investigate whether

what you did was in accord with or in opposition to bodhicitta.

—

When the splendor of bodhicitta has descended,

with remembrance and introspection as your aids

investigate every action of body, speech, and mind

to see whether they are spiritual or not.

—

One who does not delight in others’ good fortune

does not have bodhicitta within,

just as one who is angry with another person

does not have love within.

—

If bodhicitta degenerates

it is something that should be taken up again,

just as it is correct

to repair a golden vessel if it breaks.

—

If you want to produce bodhicitta, you need faith.

If you want to produce bodhicitta, you need to want it.

If you want to produce bodhicitta, you need compassion.

If you want to produce bodhicitta, meditate on these.

—

In the face of harm done to the Buddha’s

precious body, Dharma, or children, or to one’s guru,

friends, or family, cleave to moderating bodhicitta

and buckle on the armor of patience.

—

When a foundation of bodhicitta has been laid down

terrible wrongdoing is naturally stopped.

All wholesome activity comes into one’s hands;

one is free from anxiety and panic and comes to be stable.