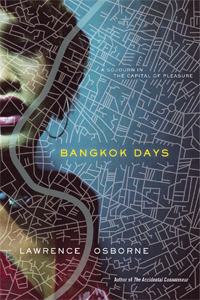

Bangkok Days: A Sojourn in the Capital of Pleasure

Lawrence Osborne

North Point, 2009

288 pp., $25.00 hardcover

Compare this book to the durian fruit, whose celestial flavor is enhanced, for some connoisseurs, by its gutterlike scent. “Bangkok Days” is a toast to the louche life, a tender, beautifully written travel memoir. It must be read; for even if, like a durian, you finally judge it unpalatable, it may have lead you to review comfortable moral positions. The book centers on aging white male Western expatriates finding reprieve from the burden of mortality in two-dollar generic Viagra hits and sex with willing women who also ask for money. These nowhere men—failures, fantasists all— wander the clubs of Bangkok and its streets, caressed by Lawrence Osborne’s heavenly language. Geoff Dyer’s travel writings and the detective novels of John Burdett cover some of the same territory, but Osborne is the subtler, more exquisite writer.

toast to the louche life, a tender, beautifully written travel memoir. It must be read; for even if, like a durian, you finally judge it unpalatable, it may have lead you to review comfortable moral positions. The book centers on aging white male Western expatriates finding reprieve from the burden of mortality in two-dollar generic Viagra hits and sex with willing women who also ask for money. These nowhere men—failures, fantasists all— wander the clubs of Bangkok and its streets, caressed by Lawrence Osborne’s heavenly language. Geoff Dyer’s travel writings and the detective novels of John Burdett cover some of the same territory, but Osborne is the subtler, more exquisite writer.

The book opens with the author sitting on his balcony, having a drink and observing a passing group of monks. He wonders if they can see his loneliness, his lostness, and his failure. This happened “a few years ago,” when the author went to Bangkok for some inexpensive dental work. He soon introduces three other Western expats—fellow denizens of the Primrose apartment complex—and Porntip, the nubile freelance prostitute they all share. Osborne-as-narrator becomes “Miss Lalant,” a corruption of “Mr. Lawrence” as pronounced by Thai female lips. Miss Lalant claims, rather coyly, to be “on the lam.”

The book traces his love affair with Bangkok over many years. It seems to hover at the borderline of fiction—not quite a novel, yet not nonfiction either. With its blurring of time and purpose, and the author’s recasting of himself as a nicknamed character, it partakes of what Osborne calls Thailand’s cosmology: “undependable, plastic, ever-shifting, mysterious.” Here expatriates come to reinvent themselves, to enjoy pleasures and services that would be unaffordable or otherwise unattainable in what Osborne deems their sterile, isolated home cultures. In Bangkok, not everything you hear from a British man should be believed. (Osborne is British, by the way).

Alone and with friends, by day and night, Miss Lalant crisscrosses the city. “We walked for a mile. Under shady trees like those of a European boulevard, down crooked Soi Tarntawan, where the smoke of roasting corn fills the air, past the Solid Club and doorways of half-sleeping girls….” One feels immersed and yearns to retrace the journeys—which would be doable, since the addresses are all given. Miss Lalant lags behind his confreres in consumption of female flesh, yet his eroticism is generalized. At one point, he claims that his “Roger the Dodger” responds to street cuisine, and drives him to eat a fried water beetle. He shows us hidden palaces and mosques; seduces and steals from a Japanese tourist; accompanies a friend to buy insecticidelaced drugs in the Khlong Tuey slum; ducks into glitzy malls; and nearly dies in ritzy Bumrungrad Hospital. Through it all, he is lonely and ecstatic in this city, with its inscrutable alphabet and “comedy of misunderstanding between East and West [that] arouses Western men so much.”

In bar after bar, he records his own and his friends’ “relentless quest for intimacy in which intimacy played no part,” and their fabulously articulate perorations, mostly about sex. Osborne revels in release from “occidental pieties.” Buddhism and Hinduism, he argues, make it possible for Bangkok to offer momentary carnal pleasures without sentimentality, guilt, or remorse.

To a degree, he’s right. There is no final and permanent hell or heaven, no specific condemnation of prostitution in Buddhism. The Buddha received courtesans respectfully. Ten kinds of wives are mentioned in the Vinaya, among them “temporary wives,” wives who are slaves, and captive wives. In a late chapter on transgendered male “katoey,” Osborne delightfully muses about the suppleness of gender in Thailand “as if everyone is subconsciously aware that you can be reborn as either gender,” and goes on to unearth historical precedents in the recognition of four genders in Buddhism.

Neither Buddhism’s own jeremiads against fleshly craving, nor its subtle, cogent deconstruction of sense pleasure as a road to happiness need be cited here. And there are other forces than Buddhist cosmology driving Thai prostitution, globalization and capitalism surely among them. Thai women’s acceptance of what they think of as their karma, binding them to a low birth and subservient status, has often been cited as a reason prostitution might feel “right” to them.

Part of the delight of this book is watching Osborne get carried away by his own observations, fantasies, and powers. Mostly these flights land harmlessly; yet he also begins to reveal a characteristic limitation of vision that compromises the book’s full humanity. He claims Thai people don’t “believe in” loneliness, because of the Buddhist doctrine of anatta [no-self ], with its concomitant acknowledgment of total interconnection. Interesting train of thought, but isn’t it also a little condescending?

I remembered why I liked Buddhism, despite being unable to adopt it: because there was no drama of love at its heart. Love simply didn’t insinuate itself into its view of animals and people, who were seen coldly and clearly for what they are… It was breathtaking, when you compared it to us, who are taught to believe in love from day one.

This stuff is pretty rich.

It’s even more difficult to swallow Osborne’s dismissal of “occidental pieties and superstitions…about the self, especially the sexual self ” as a “tirade out of the Dark Ages.” “What’s the problem?” he seems to say. “The women are all smiling! College girls!”

His heart is all for the failed, broken men of the Primrose; apparently he never got close enough to a Thai prostitute to want to describe her face, let alone learn about the necessities that drive them or the humiliations they suffer within Thai society—Osborne waves away all such concerns as chilly and repressive pieties. This is not an ugly tale about what a dollar can buy. Prostitution in Bangkok isn’t Westerners’ fault—many an Asian emperor had his vast harem, and Thai businessmen enjoy prostitutes routinely. But for a Western visitor, isn’t it a little sad, or emotionally unaesthetic, to see a huge, coarseFleischberg holding hands with a shy-looking Thai girl of twenty, dressed like a third-grade teacher, getting ready to go do you-know-what? Or how about the unwashed car-dweller my doctor-sister treats in California, who goes to Bangkok for a month each year for the purpose of living with a “temporary wife”? It’s simply not good enough to feel tender toward pathetic, ugly men finding love, or lovers, in Bangkok, without also acknowledging a downside.

The mistakenness in “Bangkok Days” is relatively harmless; the book’s publication will matter not a whit to the overall situation in Bangkok. Yet in a previous book, “The Naked Tourist” (2006), Osborne praises as a superior kind of traveler those tourists who try to be the first white person to visit uncontacted tribes. “They are not anthropologists by any means,” he says, “but they share the anthropologist’s ethos: subtle, invisible contact with fragile and remote peoples, extreme sensitivity, a light touch.” For a white person to visit a remote tribe uninvited can never be “sensitive” or “light”—only the worst form of entitled, sensationalistic voyeurism; if praising such excursions inspires one more person to go, they could cause serious, irreversible, damaging changes to such cultures. Once I asked a Peruvian anthropologist what was the biggest danger to Amazonian groups, and she said, flatly, “Contact.” At least Osborne’s praise of prostitution remains bounded; yet the self-serving perspective is the same. Let uncontacted people come out to meet tourists, if meeting is what they want. Otherwise leave them alone!

Notwithstanding its serious limitations, “Bangkok Days” ultimately asks us to examine our own closed-mindedness, to go beyond moralism to look into our humanity, our fallibility; our fertile darkness. For this it is to be praised, and for its beauty, and its honesty. It closes with an image, of the same parade of monks who gazed up at Osborne as he drank his gin and tonic on the balcony. “They had been companions of a sort, but I had never thought of them as real. They had been like painted figurines of another age, and I had underestimated how living they were.” From flat, twodimensional representations, they are now a little incised; a bas-relief. There has been a little change, a little understanding, in a city where intimacy is hard to come by.