Tibet has long filled a unique space in the popular imagination of the West. Destination of spiritual seekers, spies, and explorers, home for centuries of the Dalai Lama, it came to be seen as a mysterious, magical realm on the roof of the world. With the invention of photography in the 19th century, Westerners began to capture an imaginary Tibet with their cameras, initiating a visual record of mythmaking about the country. This perpetuation of Shangri-la stereotypes—together with the loss of early photographs by Tibetans due to the 1959 Chinese takeover—has made it a challenge to keep Tibet’s past and present alive. According to the Oxford University professor Clare Harris, however, the situation is changing as a new generation of Tibetan photographers provides fresh ways of seeing both the Tibetan homeland that is now incorporated into the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Tibet in exile.

“Photography was enlisted to fill the cartographic and epistemological void engendered by fantasies of a place called Tibet,” Harris writes in Photography and Tibet (2016), her book about how Tibet has been depicted through photography. Professor of Visual Anthropology at Oxford and Curator for Asian Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, Harris first became interested in Tibet in the 1980s, when she left her parents’ home in England to teach English for ten months in a Tibetan refugee community in northern India. “I vividly recall members of the Tibetan community telling me two important things,” she says. “One was the centrality of the ability to reproduce their culture in their own way in exile. And the second was that they didn’t want to be treated like ‘pandas in a zoo,’ observed and reduced to stereotypes either by the Chinese or by Westerners. These two points turned out to be the seeds of ideas that have developed in much of my work.”

After returning to England in 1985, Harris studied art history at the University of Cambridge and completed her PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), focusing on the reconstruction and reinvention of Tibetan culture in exile. Her dissertation was published as her first book, In the Image of Tibet: Tibetan Painting after 1959 (1999); her fourth book, The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet (2012), examines the visual and material record of Tibet created by Tibetans and outsiders. In July 2019, she was elected to the Fellowship of the British Academy, an award given to the UK’s most esteemed scholars in the humanities and social sciences.

Harris and I first met through her research work in Darjeeling, home of my family on the Tibetan side. I spoke with her recently about Photography and Tibet, which covers photographic representations of Tibet from the 19th century to the present and their relation to Tibet as a contested space. “Photography is a highly mutable medium that resists easy definition,” Harris says, “and so is the concept of Tibet. My book shows how the two are closely entangled.”

When and why were the first photographs of Tibet taken? In the 19th century, Tibet was this fascinating terra incognita for foreigners, particularly Europeans with colonial connections to Asia. The most dominant country was Britain, of course, though the Russians were coming from the west, along with others from various directions. When I began looking through the archives, it was really noticeable that there had been an explicit intention to get the first pictures of Tibet and make it visually knowable—a global competition of sorts.

“Photography is a highly mutable medium that resists easy definition, and so is the concept of Tibet.”

In Photography and Tibet, I identify a photograph taken in 1863 by a British colonial agent, Philip Egerton, as the first picture ever taken in Tibetan territory. In his attempts to cross over the Himalayas and visually document Tibet, Egerton risked life and limb before he was ejected by Tibetan officials and sent back to British India.

Can you tell us more about the colonial context at the time? Empires, like the British Empire, produced massive textual documentation as part of colonial expansion, colonization, and administration. Alongside the bureaucrats were scientists, explorers, military people, intelligence officers, missionaries, and so on. They all had reasons to acquire visual documentation.

Early photographs of Tibet have a particular saliency and value because they relate to geopolitical framing, revealing a way of seeing the country inflected by the agendas of different nations and the professional activities of the people taking the pictures. It’s important to note that Tibetans had little or no control over this mode of image making.

What challenges did the people taking the pictures encounter? In the 19th century it was extremely hard to take pictures in Tibet—logistically, because access was forbidden to foreigners; technologically, since it was the era of glass plate photography; and physically, because of the terrain.

My research has revealed that the solution was often to photograph Tibetans outside Tibet. Through visual analysis, comparison with other photographs and archival research—coupled with knowledge of the relevant textual information and particular locations—I came to realize that many “genuine” pictures of Tibet had actually been taken in Darjeeling and other Himalayan areas that were readily accessible to the British in particular. For example, Tibetans in Darjeeling were photographed by Europeans for publications and postcards, as if the Tibetans were in Tibet itself.

In your book you mention the difficulty of tracing the history of the relationship between photography and Tibet. Why is this history hard to reconstruct? We’re talking about a community that experienced a massive rupture from the 1950s onward because of the Chinese takeover of the country. This has led to a loss of material as a result of destruction and migration. There’s also restricted access to visual archives in the PRC. When I was in Tibet, I tried to find out more about photographs that had been taken by Tibetans in the first half of the 20th century; they were said to be in archives in Lhasa, but there was no way a foreigner like me would be allowed to see them. As far as I know, Tibetans can’t access these collections either, and such archives are often even off limits to Chinese researchers. Important archives of photographic material exist in India, for example in Dharamsala, but they primarily relate to the period after the move into exile in the 1960s.

Is it actually impossible, then, to reconstruct Tibet’s visual history? I believe that with persistence it can be done, in spite of the tremendous archival gaps. The capacity to visualize the country as it was before 1959 is vital for memory construction and cultural pride, and is essential to counteract highly politicized readings of Tibet’s past. Going back to the 1960s and 70s, photography was used by the Chinese state to present a propagandistic narrative that portrayed Tibet as a feudal backwater, criticized the supposed iniquities of Tibetan Buddhism, and undermined the status of Tibetans. That’s the trouble with photography: it can be used to tell any story you want it to tell.

It’s interesting that some of your projects are related not only to reconstructing Tibet’s visual history but also to making it accessible. One of my motivations has been to make the photographic material in Western museums and archives available to Tibetans. That’s why at the Pitt Rivers Museum we have the Tibet Album project, a website showing 6,000 photographs related to Tibet’s history before 1950—and that’s only a fragment of the huge quantities of pictures available in other museums in Britain alone. My dream is that all the archives in the world with Tibetan photographs will work together to create a global visual archive, to enable modes of remembering and researching Tibet.

“The capacity to visualize [Tibet] as it was before 1959 is vital for memory construction and cultural pride.”

As an academic and a curator, I think our ethical obligation is to make those things that have such powerful stories to tell, with such emotional resonance, available to the people for whom they have the greatest significance. In 2019 we created “My Tibet Museum,” an event at the Pitt Rivers for Tibetan teenagers in the UK. We showed them photographs on the Tibet Album website and from the museum’s collection. I was shocked to discover that among those under 18 years old, some had never viewed pictures of pre-1959 Tibet; they had never even seen an old photograph of the Potala Palace. We had extraordinarily emotional moments, when young Tibetans looked at the photos and said things like “That’s where my grandparents lived.” This is an example of the powerful role museums can play in reconnecting people with the visual history of their homeland and their heritage.

To what extent have Tibetans gained control of the camera? One objective of Photography and Tibet was to acknowledge Tibetan agency in the creation of photographs of Tibet, so the discovery of pictures taken by the 13th Dalai Lama in the early 20th century, for example, was fantastic! More recently, Tibetans have gained far greater control of the camera. The creation of digital images on phones and computers has proved crucial for communicating beyond geopolitical boundaries and making connections between Tibetans in the PRC and in exile. Many of these pictures are personal or family photographs—it’s a vernacular photography that’s mobile and not politically sensitive, so that it can surmount the great Chinese firewall. Other individuals are using cameras for more artistic purposes and to illustrate contemporary Tibetan experiences.

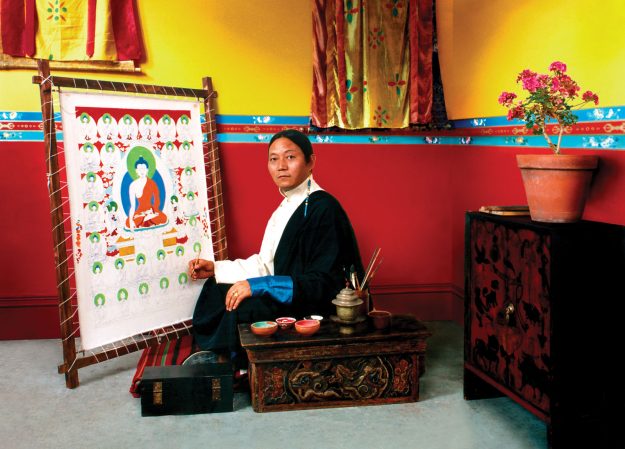

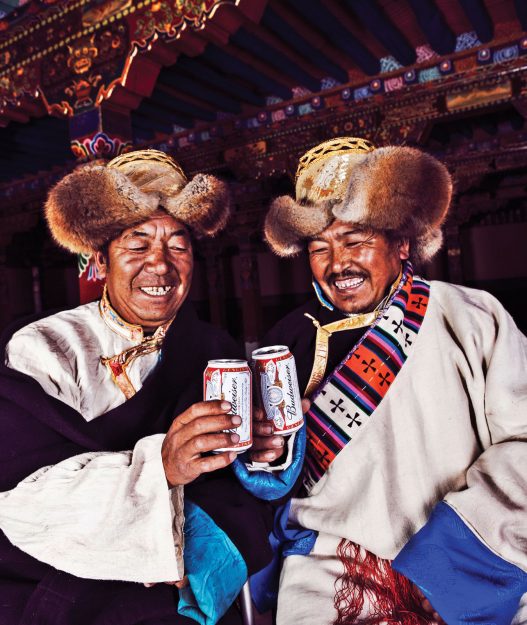

Who are some of these individuals? In 2018, the Tibetan photographer, curator, and designer Nyema Droma—a young woman who has lived in Britain and China—developed an exhibition for the Pitt Rivers called Performing Tibetan Identities. Droma examined hundreds of 19th- and early 20th-century photographs of Tibetans in the museum’s collection as she considered how members of her generation, both in China and in the diaspora in Europe, self-fashion their image. She then set out to take portraits of her friends in both locations.

This exhibition is unique in acknowledging the “two Tibets”: the homeland Tibet that is now incorporated into the PRC, and the Tibet of exile and diaspora. I’m extremely proud that Performing Tibetan Identities was based on works created by a young Tibetan female photographer who determined how she wanted herself and her generation to be represented. By emphasizing hybridity and celebrating Tibetan-ness in a different guise from what most people are familiar with, Droma overturned stereotypes generated in the West and in China, past and present. She’s absolutely in control of the camera, and of which images created by her camera appear publicly in the museum, in the exhibition book, and online.

Droma is one of many young Tibetans using photography as their medium, but “control of the camera” is not just about the capacity to take pictures. It’s also about being able to circulate them and determine the accompanying narrative—as foreigners have done for decades—to tell the stories Tibetans want to relay to the outside world. This remains difficult, as there are still those who seek to make Tibet and Tibetans invisible in the global public domain.

Do you think many Tibetans are eager to represent Tibet and Tibetan-ness? There are definitely Tibetan photographers who want to make work to remind the world of Tibetan culture, but in a way that’s not the stereotypical Shangri-la version of Tibet that the West is particularly keen on, or China’s propagandized version. The question is how can Tibetans squeeze themselves in between these two big blocks of cultural and political power?

There are photographers who want to speak to Tibet and its politics. For others, “Tibet” and “Tibetan” is almost a brand, a selling point for their work involving a manipulation of iconography that’s distinctively Tibetan. Then there are those who consider themselves artists first and foremost. It’s important for all these things to be possible.

Of course, there’s also a burden placed on individuals who may be seen or even required by others to represent their community. One of my Oxford students who’s from the exile community in India is doing wonderful work rethinking how Tibet is depicted in museums, but he’s conscious that he’s just one individual and the community is incredibly diverse. In any event, the talent of the younger generation of Tibetans, wherever they were born or now live, is a source for optimism, as they’ll be the ones who forge new ways of determining how Tibet is visualized and represented in the future.