Eviscerating somebody by lightning, breaking up lovers (or bringing them together), becoming invisible, exorcising demons, and raising corpses into zombie assassins. These may not be the kinds of activities we generally associate with Buddhism, but casting spells and curses has long been integral to everyday Buddhist life, from the earliest days up to the present.

Despite its historical importance, magic has been one of the most neglected aspects of Buddhist traditions in the past several decades as many have sought to portray the religion as rational, philosophical, and free from superstition and ritual. Since the modern discipline of Buddhist studies first emerged in the 19th century, the magical dimensions of Buddhism have often been downplayed or ignored altogether. Even Buddhists themselves have dismissed these aspects as corrupted forms of “pure” Buddhism that cater to the needs of the unlettered masses, rather than being a fundamental part of Buddhist life.

In recent years, however, magical practices have begun to gain currency as a serious topic in academic and mainstream Buddhist circles, thanks to the work of scholars like Sam van Schaik. A textual historian who currently heads the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme, van Schaik was a doctoral student when he stumbled upon a Tibetan book of spells written roughly one thousand years ago. Originally found in a cave shrine along the Silk Road in Dunhuang, western China, the spellbook made van Schaik realize just how little attention was paid to magic in Buddhist literature.

Over twenty years later, van Schaik revisited the Dunhuang spellbook in his new book Buddhist Magic: Divination, Healing, and Enchantment through the Ages, which argues that magical rites can provide a better understanding of the socio-economic networks of early Buddhist communities as well as a fuller picture of their everyday existence.

Tricycle recently spoke with van Schaik, in a bicontinental Zoom room, about how he approaches magical literature as a textual archaeologist and why it’s important to dispel misperceptions about this lesser-known side of Buddhist traditions.

When did you first encounter Buddhist magic in action? As a teenager, I spent several years living in Nepal and Bhutan because my parents worked overseas, splitting time between Asia and Africa. In retrospect, living in cities like Kathmandu and Thimphu exposed a gap between how Buddhist traditions have and continue to be studied and the ways they are practiced. If you’ve spent any time in Asian countries, you may notice that the “Buddhism” you see on the streets or in temples isn’t always commensurate with what is presented to us in classic books or in popular notions about Buddhism being a philosophy, not a religion.

Whether you’re in Thailand, Bhutan, or Japan, there is a sense in which everyday Buddhism involves protective talismans, prosperity rituals, and incantations for summoning gods and spirits. You’ll probably see a lot more practical magic than meditation or philosophical study, which invites us to examine our preconceived notions about what “is” or “isn’t” really Buddhist.

Your book cites magic and healing rituals as key reasons for why Buddhism was able to take root, flourish, and remain relevant outside of India. What else do we gain by looking at Buddhist history through the lens of magic? Solutions for protecting harvests, pacifying threatening ogres, finding treasure, dealing with the loss of a child, resolving marital discord, and figuring out when to start a business venture were all within a Buddhist sorcerer’s repertoire. These are the kinds of professional services that magic users, or vidyadharas [“holders of magic”], offered their clients. It’s hard to say who exactly performed these rites, but the written and archaeological record suggests that their expertise developed out of Indian Buddhist monasteries, where monks and nuns regularly performed these services. We know from 20th-century and contemporary Tibet that lay specialists and non-ordained tantric practitioners, such as ngakpas, were also part of the magical gig economy.

These practices endured in non-Buddhist regions because they addressed real-world problems. Ritual specialists earned the public’s trust through their use of magic and were able to establish themselves in new regions, which was critical to the transmission of Buddhism along the Silk Road. What the Tibetan book of spells offers is insight into the day-to-day activities, needs, and relationships between the local lama, farmer, merchant, and emperor.

The power of magic users stems from their ability to manipulate the elements, emotions, and cosmic forces in ways that could be construed as circumventing karmic laws of cause and effect. How does the logic of karma factor into magical thinking? The Dunhuang manuscripts present a worldview in which illness and misfortune are personified and can be dealt with through enchantments, spirit traps, mandalas, and other symbolic activities. Because Buddhist magical practices are clear-cut prescriptions for specific maladies, we can view them as a form of homeopathic medicine rather than fate-altering solutions. For instance, there are practical remedies for preventing unwanted pregnancies, easing the pains of childbirth, improving sexual performance, and curing headaches.

A few Tibetan lamas once told me that performing these rites may ease suffering, if only temporarily, but if your karma spells death, then no magico-medical treatment or long-life practice will alter that inevitable outcome. Karma still trumps everything else.

Of the spells you translated, were there any in particular that stood out? One divination, aimed at robbing someone of their ability to speak, instructs the practitioner to write the target’s name on a piece of paper, recite a mantra, and place it “in the mouth.” The scribe included a handwritten note—“in your own mouth”—as if to clarify any anticipated confusion. I love how the text preserves fragments like these, allowing us to step into the imaginary worlds of the agents who used them.

I’ve always been fascinated by the power of invisibility, and the scriptures lay out several methods for becoming invisible. One of them involves catching a frog that is moving east on the eighth day of the first month of summer and binding its feet with string. As I translated clauses like these, I asked myself, did anyone really do this? My best guess is that this level of detail would be unnecessary unless real people were actually performing these spells.

Many of the spells are protective in nature but some of them are explicitly violent, like those for mutilating or killing enemies. They seem to be at odds with the larger Buddhist framework of compassion. Stories of violent magic abound in scriptures, biographies of monks, and contemporary practices. It is important to acknowledge the presence of violence, especially when dealing with spells that can be aggressive or even lethal. While some of the texts provide ethical justification (yogins should act with a sympathetic mind or else their actions will rebound), this is not always the case.

There is no avoiding the fact that aggressive magic was to be taken literally, not metaphorically or spiritually, and this remains an unresolved tension. One effect of looking at these rituals for what they are and not what we want them to be is that we can more clearly see how Buddhism was—and is—embedded in cultures where moral principles are cherished, but can be cast aside in times of need.

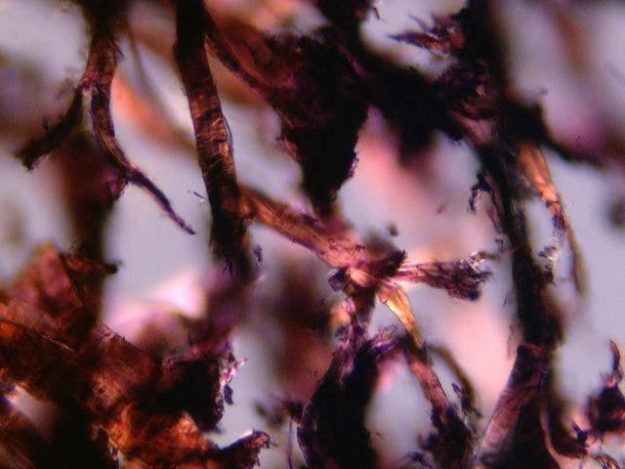

The materiality of a text can tell us a lot about how it was used and who used it. What about the spellbook gives us a glimpse into its past lives? The manuscript’s weathered pages, grease marks, and evident wear and tear are all signs that it was used extensively. Its Tibetan cursive writing style helps date the text to the end of the Tibetan empire (ca. late 8th to early 9th century), and variations in the handwriting indicate that multiple authors contributed to the book over time, rather than its being written all at once. I worked with paper scientist Agnieszka Helman-Wazny to analyze its fibers under a microscope, leading us to believe that the spellbook was made from recycled textiles and was very likely a local product.

Historians of religion tend to romanticize the Dunhuang library caves as sacred places for meditation. Others paint a less rosy picture, arguing that the caves were basically graveyards because they originally functioned as funerary shrines. The “collection” we have inherited is actually an accumulation of deposits from deceased owners, some of them high-ranking Buddhist officials and monastics. This context bears clues that inform how we should approach our early book of spells.

How might reading manuscripts like these nuance our patchwork understanding of Buddhism then and now? For over the last two and a half millennia, magic has eased suffering and built bridges between the lofty aims of Buddhism and the people who support it. What magical literature provides is a messy record of peoples’ lives. Instead of downplaying texts like these, or keeping them out of sight, they should be celebrated because they allow us to rethink Buddhism from the ground up.

Elite scriptures from the Dunhuang collection, such as the Prajnaparamita [The Perfection of Wisdom], are certainly important to study, but the personal letters, shopping lists, and magical manuals are far from the “sacred waste” they were initially thought to be by early 20th-century European explorers. If we are to better understand the way Buddhism has worked in the past, the way it still works in many places today, and how it might work in the future, we might start by making a little more room for magic.

***

A Selection of Magical Rites from the 10th-Century Tibetan Book of Spells

—Translated by Sam van Schaik and edited for brevity and clarity

To strike a foe by lightning or a meteor:

Make a mudra by drawing the middle, ring, and pinky finger of your left hand into your palm and raise your forefinger; cross your thumb and forefinger across the middle joint. Recite the mantra, then use the mudra to indicate where it will strike. Destruction will come quickly.

To break up two lovers:

Tread on both individuals’ family names with your feet. If they do not separate, say the mantra 200 times and visualize the two of them breaking up. The following day, they will no longer be lovers.

To reconcile two people who are fighting:

Do the same as in the previous ritual, but visualize the two resolving their quarrel.

To summon and control an ogre:

Boil peach and willow in water with three ounces of frankincense, cloves, and black cumin. Take the leftovers from the five offerings and pour into a chipped pot. Break the peach and willow rods into three pieces, stir, and perform 108 recitations. The ogre will appear and become your servant.

To gain heightened perception:

Place the tears of a recently deceased person into the palm of your hand, and then mix them with dust from the mat that was in contact with the corpse. If you anoint your eyes with the mixture, you will be able to see gods and spirits within nine miles. If you put it on your ears first, you will hear all sounds.

To become a great Buddhist sorcerer:

Make offerings from the branches of a soapberry tree. Anoint everything from ceiling to floor with yak butter, white honey, and yogurt from wild cattle. Perform 21 burnt offerings in front of the Thousand-Armed and Thousand-Faced One [the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara]. Mix animal bile and 10 spoons of yogurt into flat beer. Say the mantra 1,008 times, and drip this paste onto your body. Gods and dragons, humans, and nonhumans will fall under your power.