In the early seventies, my life was totally focused on formal Zen meditation practice. I was living full-time at the Rochester Zen Center, where each day we residents would sit for three to four hours. The exception was the one week each month when we sat for even longer periods in silent retreat. During retreats there was great emphasis on achieving a “breakthrough experience,” or kensho. At the time I thought this was the whole of Zen practice. I had committed my life to it. But that changed in 1975, when I discovered that I wasn’t seeing the full picture. That was the year I met Thich Nhat Hanh.

Thich Nhat Hanh was not a household name back then. I became aware of his work when a friend mailed me a New York Times op-ed from December 1972 on the Buddhist peace movement in Vietnam. The column was perceptive and compassionate. It focused on nonviolence and reconciliation, emphasizing the extreme suffering inflicted on ordinary Vietnamese citizens by two warring factions locked in a violent struggle for dominance. The author, of course, was Thich Nhat Hanh, or Thay (“teacher”), as his students called him.

I had never heard of Thay, nor had I ever heard of any Zen monk so deeply involved in a nonviolent, anti-war movement. At that point in its development, the American Zen community focused on teachings and practices related to an “on-the-cushion” meditative life. But I soon became determined to track this monk down. Through the Catholic peace movement and the organization Fellowship of Reconciliation, the communities to whom Thay was best known at that time, I was able to locate him in Paris. I wrote him a letter, and he wrote me back.

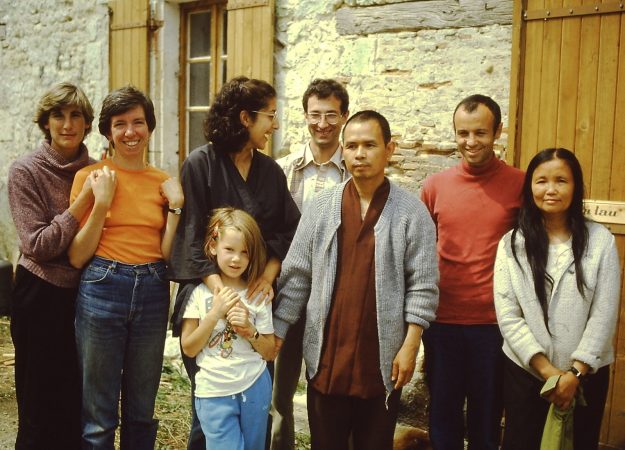

This developed into a correspondence with the eventual co-founders of Plum Village, Thay and his student from Vietnam, Cao Ngoc Phuong, or Sister Phuong as she was called. (She later took the name Sister Chan Khong.) I started publicizing the activities of their group, the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation, among the larger Buddhist community in the States and raising funds for their projects to alleviate the suffering of war refugees in Vietnam. However, it would still be several years before I was able to make the trip to France and meet them face-to-face—an encounter that would challenge almost everything I thought I knew about Zen.

In 1975, the Plum Village monastery in southern France was hardly even a dream. Thay was living in a small apartment in the Parisian suburb of Sceaux along with Sister Phoung and was assisted by an American secretary, Mobi Ho. At that time he was not publicly functioning as a Zen teacher. His main role in France was as the representative of the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam (UBC) and the leader of the Vietnamese Buddhist Peace Delegation.

Thay did not wear monastic robes then. He dressed simply in brown pants and shirts; in colder weather he favored a type of brown jacket, modeling himself after French worker priests and ordained Catholic activists like the Berrigan brothers in the States. While still personally following their monastic commitments, these men lived outside the formal structures and strictures of the Church and actively participated in bettering the lives of their society. At this time in his life, Thay mostly clashed with the overseas Vietnamese community, as the majority were either actively pro-Saigon or pro–National Liberation Front (NLF). Of course, Thay was neither.

Life in Sceaux did not look much like my meditation-packed days in Rochester. Most of our time was dedicated to fundraising and letter-writing to help refugees, orphans, and other displaced and forgotten Vietnamese citizens and publicizing the movement for peace and reconciliation being conducted by UBC. The days were long, and the news from Vietnam was often heartbreaking.

Yet there was always time for meditation—and mindful outdoor walking. Every day there would be some downtime from the refugee work that Thay and Phuong were focused on, and we would usually take a walk along the tree-lined streets of Sceaux to a nearby park. But although Thay was deeply loved by all, not everyone wanted to take the afternoon walk with him. His naturally slow-paced mindful walking meant that he and his companions would rarely reach the beautiful park; most of the time they didn’t get much farther than a few blocks from the apartment before they had to turn back.

There were plenty of lively activities to enjoy together: discussions on dharma and Buddhist social work, tea drinking, poetry recitation, and meal preparation. There also was a lot of singing, especially after dinner. Sister Phuong’s voice was mesmerizing, and her brother was a well-known nightclub singer in South Vietnam and a frequent visitor to their apartment. He was not involved in their Buddhist or political activities, but we all welcomed him and enjoyed his energetic, humorous songs and his guitar accompaniment.

More than being simply an exemplar of a Buddhist social activist and tireless proponent of nonviolence (which he definitely was!), Thay was a powerful Zen teacher for me. During the several weeks when I lived with him in Sceaux, he let no opportunity pass without either subtly or forthrightly challenging and even undermining most of the Zen practice tenets that I tightly held to at that time.

When I would proudly tell him about the many hours we sat in meditation at the Zen Center, he would counter by deflating the importance of this formal practice and saying that how we led our daily lives was the most important part of Zen. He asked me this: If one sits three hours daily in formal meditation and spends the rest of one’s waking hours doing various other activities, which part of the day is more important to one’s well-being? If all one’s emphasis is on the quality of one’s three-hour meditation life and not on the quality of one’s daily life, isn’t this life acutely out of balance? The fact that he was more interested in the lives of practitioners than in their practice baffled me.

And he repeatedly interrogated me: Are these American Zen practitioners happy? Do they have good family relationships? Do they know how to love?

These questions were not entirely rhetorical. He had had little to no contact with the developments of Zen Buddhism in the West, which made me a source of great interest, curiosity, and perhaps even amusement for him. He was surprised that at American Buddhist centers and temples practitioners would chant Buddhist sutras and other prayers and texts in a language that they didn’t understand—Japanese, Tibetan, or Chinese. He insisted that Buddhism can only thrive in the West, as it has in Asia, when it adopts the cultural norms of the country it is entering. Buddhist texts and prayers have meaning, he would say, and need to be chanted in the chanter’s native language.

I remember how, after talking with him each day, I would take a long afternoon walk with my wife, Erika, attempting to digest and process what Thay had been throwing at me over the past twenty-four hours. It was hard to accept this intense shift he was proposing to me and the radical and open quality of his thinking. Confronted with his continued onslaught against all my cherished beliefs about Zen practice, I was initially defensive, then confused, then a bit distraught, and finally, liberated. The lopsided practice that I had known for the previous seven years now had the opportunity to become more balanced or even completely refashioned. Such was his effect on me.

It seemed that no matter what belief I held to at the time, Thay took great delight in directly challenging it.

It seemed that no matter what belief I held to at the time, Thay took great delight in directly challenging it. He knew I was a strict vegetarian, but at that time he and Phuong followed a traditional Vietnamese eating style that from time to time might include small amounts of fish or meat. I remember how one day, when the food being prepared had some fish or meat in it, Thay looked directly at me as we sat at the dining table and said with a mischievous smile, “I know that Fred, being a good bodhisattva, would never refuse to eat food that someone especially prepared for him.”

Thay had a visceral distaste for the austere and samurai-like quality of the Zen I was training in. I shared with him the “seriousness” of how we practiced. For instance, no moving was allowed during periods of sitting meditation. When I mentioned the continual application by meditation hall monitors of the keisaku (wooden stick) on the shoulders of meditators to spur them on to more focused and energetic meditation, he winced. Then he talked to me about nonviolence and how Buddhists shouldn’t be violent or aggressive toward other people or to their own bodies.

Whenever I mentioned the single-minded focus of our Zen retreats on having a breakthrough experience, he would regale me with Zen anecdotes about “do or die” practitioners who actually did die without experiencing an awakening. He would tell me other stories to show the futility of that aggressive mentality and the harm such “do or die” encouragement talks could cause if they were not delivered skillfully.

At the Zen Center, nearly everyone who was serious about practice would be given the koan Mu, which became the focus of their meditative life. The tradition was to work on this koan until one had a kensho experience: one year, three years, five years—one stayed with this practice, no matter what! Thay found this to be incredibly rigid. He said that meditation practices, including koan practice, were there simply to aid the practitioner in awakening. His instruction to me—“If you’re not getting good results from one practice, talk with your teacher and try another”— directly contradicted the meditative mentorship I had been receiving. He believed that the meditative life should be a creative and experimental journey and that one should receive meditative practices that would produce the healing and transformation necessary for oneself.

Thay taught me about a more open, spacious, and gentle Zen practice that he had learned from his teachers. Zen practice, he would say, is about a continual wakefulness and ripening, not intense periods of targeted meditative practice. Over and over he would tell me that to be truly beneficial to the practitioner and society, transformation must occur in daily life and not just on the meditation cushion or at the meditation center. He explained to me how in Vietnam Zen arts such as flower arranging and tea ceremony followed an aesthetic that was less formal and rigid than their Japanese counterparts. He emphasized the naturalness, joy, and spontaneity of these practices, especially the tea ceremony, which for Thay was not only about enjoyment of the tea but also about drinking tea together with others.

Over and over he would tell me . . . transformation must occur in daily life and not just on the meditation cushion.

Another highlight of our time with Thay was the arrival of Daniel Berrigan, the nontraditional Jesuit priest who was a close friend of his. Dan recorded his talks with Thay, and these would become the basis of a future book, The Raft Is Not the Shore: Conversations Toward a Buddhist-Christian Awareness. Dan was a wonderful man, a great storyteller, a man of true integrity who looked to Thay as a brother and mentor.

For Dan, Thay was a fellow celibate monastic, nonviolent activist, poet, writer, and deeply committed contemplative. Dan was unable to find such mentors within his own tradition (Thomas Merton had died in 1968), and it was both inspiring and instructive for me to listen to (and sometimes participate in) their dialogues about the mistaken belief that the activist and meditative life were at odds.

They both believed strongly that a contemplative discipline was essential for the maintenance of the emotional well-being of the committed activist. Thay said that activities to better the world and end war were simply “love in action,” and he based his Buddhist activism on a nondual view of reality.

Both men shared the tenet that those who believed strongly in nonviolence and the contemplative life as the basis of societal transformation needed to establish what Thay called “communities of resistance.”

I once went with Sister Phuong to a Vietnamese temple in Paris to meet the resident monk, who, she said, respected Thay and would meet with him privately but could not receive him in the temple because of fear of parishioner backlash. When I returned to the apartment, Thay asked me if I had seen the temple’s altar dedicated to Kuan Yin, the bodhisattva of compassion. I still feel a chill when I remember how he looked straight at me and asked, “Fred, do you know the best offering to make to the bodhisattva of compassion?” He then held up his two hands, and said, “These are the true offerings to give her!”

During our stay that fall, a deep sadness had begun to take hold of Thay and Sister Phuong. For many months, with the peace accords signed, they had been seeking visas from the Vietnamese embassy in Paris to return to Vietnam. Both Thay and Phuong intensely wanted to return to their homeland, to see once more the friends and family they loved and missed so dearly. And what was equally important, now that the war had ended they wanted to return to participate in the rebuilding of their country as it recovered from social and economic devastation. I recall Thay saying that he wanted to work among Vietnam’s hill tribes, which had suffered greatly in the past under the ruling Vietnamese. But after being given an endless and frustrating runaround for months by the NLF representatives in Paris, he and Phuong finally realized that they were never going to be given an entry visa by the new regime; their temporary exile in the West would now become permanent. Their grief was palpable.

On the last day of our visit to Sceaux, Thay and Sister Phuong drove us to the airport. In Parisian traffic, the journey took almost two hours. It was on that ride that Thay began to tell me the history of the Tiep Hien Order (now called the Order of Interbeing) and the Buddhist teachings that underpinned its precepts and activities.

I was so inspired that I spontaneously asked him to ordain me right there in the car. Thay calmed me down and said that with the disruption caused by the war and his exile to France, there had been no ordinations after those of the original six members. At that point in time, he was unsure whether the order would have a future even in Vietnam, much less the rest of the world. He assured, however, me that if it was ever resuscitated, he would not forget my aspiration.

POSTSCRIPT, NOVEMBER 2020

I wrote the above reflection in October 2010 while in St. Petersburg, Florida. Sitting here in my Tampa home as an ordained member of the now global Order of Interbeing, reading over these recollections that I wrote ten years ago, I feel so fortunate to have encountered Thay when he was in his forties and a relative unknown in the world of Buddhism and so to have been allowed many personal interactions with him. I did not realize at the time where history would be taking Thay. I made no recordings and took no notes of our conversations in 1975 or during my many visits in the following decades. I can rely only on my memory, which I know is an imperfect instrument.

Of course, over time he was discovered, as he deserved to be, and millions of Buddhists and non-Buddhists have been able to benefit from his deep wisdom and compassion. As true bodhisattvas do, he showed me the Way in this life—not just by his words but more importantly by his presence, his embodiment of everything he taught. I can only bow deeply to him.