The Vinaya, or collection of rules for Buddhist monks and nuns, requires celibacy—a commitment to following the Buddha’s path to enlightenment, free from the distractions of sexual relationships. But in honor of Valentine’s Day, a holiday that celebrates romance, we’re revisiting the legacies of three Buddhist Romeos who rejected a life of celibacy in favor of the pleasures of love.

These Buddhists fell short of monastic expectations by inviting sexual partners—and oftentimes multiple partners—into their practice. While some indulged in hedonism, others viewed sex not as a rebellious rejection of tradition, but an essential part of the human experience, even considering it compatible with the ultimate goal of liberation. Tricycle takes a look at a few Buddhists’ escapades in love.

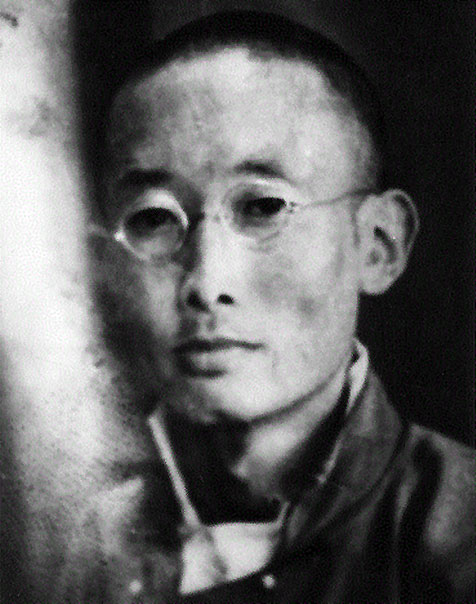

Genden Chopel (1903–1951)

One of the most colorful and controversial figures of the modern Tibetan Buddhist world, Genden Chopel is known for his lustful poetry and erotic writings. Born in 1903 in Amdo, Tibet, Chopel spent his early years studying in monasteries, quickly establishing himself as a scholar, artist, poet, and historian.

A recognized tulku, or reincarnated lama, Chopel was a celibate monk until his early thirties. His life took a turn in 1934, when he left Tibet for India. Around this time Chopel seems to have abandoned his monastic vows, and he became intimate with not just one, but many women. From these encounters, he wrote the treatises on passion, which are perhaps the most famous works of erotica in Tibetan Buddhist literature. Drawing from classical Sanskrit texts and his own experiences of intimacy, Chopel writes about the spiritual and physical benefits of love-making, enumerates types of pleasure, and describes effective sex positions. In the following verse, Chopel describes the sensation of orgasmic bliss:

The emerging essence made from one’s own indestructible elements,

This honey-like taste born from one’s own self-arisen body,

Experienced through the hundred thousand pores,

This is something not tasted even by the tongue of the gods in heaven.(From The Passion Book: A Tibetan Guide to Love & Sex trans. by Donald S. Lopez Jr. and Thupten Jinpa)

Through his sexual encounters, Chopel charted his own path to liberation. He used his poetry to push back against conventional attitudes that regarded sex as a transgression. The ex-monk publicly criticized religious and secular laws for suppressing sexual desires, which he saw as natural. Chopel believed that all aspects of human experience, with the right motivation, had the potential to be expressions of the awakened state and thereby paths to enlightenment.

Sixth Dalai Lama (1683–1706)

The Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, took no shame in worldly indulgences; he enjoyed drinking wine, singing, writing love poetry, and visiting brothels. His legacy is characterized by controversy, from his secretive birth to his lovesick youth and premature death at the age of 24.

The Fifth Dalai Lama died in 1682, but news of his passing was kept secret for 15 years to prevent political instability while monks searched for his next incarnation. So, for the first 14 years of his life, Tsangyang Gyatso lived under what today amounts to house arrest. Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that the young boy did not take well to his new life as the leader of Tibet. Disinterested in all the trappings of the position, Tsangyang Gyatso renounced his vows, opting instead to live as a layman—the only time a Dalai Lama has done so.

Many tried to persuade him to at least keep his novice vows, but the Sixth Dalai Lama refused. After renouncing renunciation, Tsangyang Gyatso lived life how he pleased, which, it seemed, meant frequenting bars and picking up women. Though notorious for his playboy lifestyle—unbefitting for a Tibetan theocrat—the Sixth Dalai Lama is largely remembered as one of Tibet’s greatest poets. He wrote poems that were erotic and bittersweet, capturing the pains and pleasures of being in love:

Doing what my lover wishes

I lose my chance for dharma.

But wandering in lonely mountain retreats

Opposes my lover’s wishes.(From The Turquoise Bee: The Lovesongs of the Sixth Dalai Lama trans. by Rick Fields and Brian Cutillo)

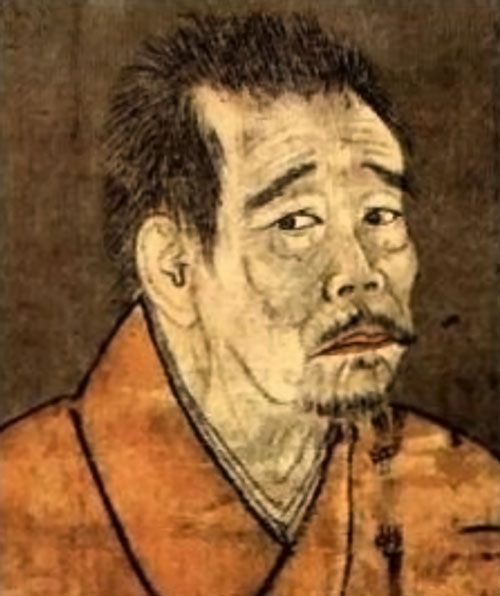

Zen Master Ikkyu Sojun (1394–1481)

A roundup of Buddhist romantics is not complete without Ikkyu Sojun, the iconoclastic Japanese Zen monk and poet. Both a serious student of Zen and a master of erotic poetry, Ikkyu shook up the Zen establishment with his unorthodox ways.

Ikkyu grew up in a Rinzai Zen temple, where he studied Buddhist scripture and Chinese poetry. As a youth, Ikkyu was precocious and opinionated. He showed immense talent in writing poetry, through which he would channel all his frustrations about temple life. Ikkyu often criticized the Zen political establishment for its corruption and complacency. He eventually grew so discouraged by the bureaucratic nature of Zen that he left temple life behind, becoming a vagabond at the age of 33.

Breaking all the taboos of a Zen monk, Ikkyu drank, frequented brothels, grew out his hair and beard, and wrote erotic poetry about his sexual exploits. In Ikkyu’s eyes, sex and Zen could happily coexist. He preached that sexual desire was an essential part of human nature, and to deny sexual desire was to go against the purpose of Zen—discovering one’s true nature. Later in his life, Ikkyu fell in love with a young blind singer named Mori, who became a frequent subject in his poems:

With a young beauty, sporting in deep love play;

We sit in the pavilion, a pleasure girl and this Zen monk.

Enraptured by hugs and kisses.

I certainly don’t feel as if I am burning in hell.(From Wild Ways: Zen Poems of Ikkyu trans. by John Stevens)

Ikkyu is unabashed about his status as both a Zen monk and lover, and he even went so far as to mock the idea that monastics would burn in hell if they engaged in sex. Adopting the epithet “Crazy Cloud,” Ikkyu wandered for several decades, devoting his life to the spirit of Zen and the joys of love play.

Ten days in this temple and my mind is reeling!

Between my legs the red thread stretches and stretches.

If you come some other day and ask for me,

Better look in a fish stall, a sake shop, or a brothel.(From Wild Ways: Zen Poems of Ikkyu trans. by John Stevens)