Playing in the Zone: Exploring the Spiritual Dimensions of Sports

Andrew Cooper

Shambhala: Boston, 1998

160 pp.; $13 (paper)

Early on in this immensely insightful but skewed study, Andrew Cooper, a freelance writer and editor and longtime Zen student, describes being offered “years ago,” while a resident at the Zen Center of Los Angeles, a free ticket to a Lakers game. After much indecision he chose the game over the evening’s meditation session, but he also came to realize that “two parts of myself, both rooted firmly and deeply, were strangers to one another.” One part was “the spiritual impulse,” the other was “the pull of sports.” His attempt to reconcile the two, begun on that night, has resulted in this book.

Playing in the Zone employs what the author calls a “universalist” rather than a Buddhist approach, expressing ideas worth heeding by anyone who hopes to understand all manifestations of the self including, for instance, the penchant for shouting at the TV when a favored player swishes a ball through a hoop. Cooper roams far to explore the spiritual dimensions of sports: he delves into his own memories and experiences; draws on mythology, Jungian theory, history, and an impressive body of sports-oriented literature; and talks with experts including former pro footballer David Meggyesy, psychologist Tom Singer, and Esalen founder Michael Murphy, author of Golf in the Kingdom, a best-selling novel about the spiritual aspects of golf.

From these encounters Cooper draws some provocative conclusions. The most important of these are summarized in his statement “Sport approaches the sacred not by means of a spiritual path, a way, but through the eros of excellence.” That is, sport, while it may reveal facets of the sacred, is not itself a paved path toward the sacred; it is not a spiritual discipline. For, as Cooper says, “by their nature, spiritual traditions regard self-knowledge as a necessary virtue and explicit goal. . . . But in sport self-knowledge is not a virtue of significant measure.”

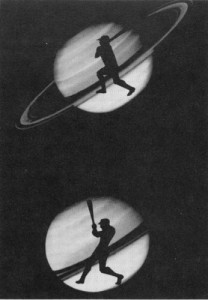

What Cooper believes sport does offer is indicated in his book’s title. By giving players access to the “zone,” a state that Cooper likens to flow, a term described in the well-known book of the same name by psychologist Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi, as an expression of “deep concentration . . . lack of self-consciousness, and self-transcendence,” sport allows those who participate in it to experience revelations of the sacred, satisfying their “deep hunger to connect with a realm of mythic meaning.” This may be so. But do all actions have mythic resonance? As surely as the sacred exists, the mundane does, too.

Sport calls its participants and viewers not only to the sacred but also to base violence, chauvanistic loyalties, and the madness of the crowd. Cooper acknowledges this fact, but only briefly, focusing instead on what he and no doubt most others consider sport’s more positive attributes. Moreover, in attempting to elevate sport’s more brutal aspects to mythic dimensions (“Mars, or Ares, is not . . . the only god at work in sport . . . . Sport also honors the martial goddess Athena”), he seems to be trying to make a pigskin purse out of a sow’s ear. As certainly as sport produces the magic of Michael Jordan at the top of his game, it produces a temporarily deranged baseball fan yelling “Kill the ump” as well.