For me, growing up Buddhist in Northern California in the early 1960s was sometimes difficult. There were very few Buddhists around, and many Americans looked at Buddhism as some kind of weird Asian cult. Fortunately, things have changed enormously since then. Buddhism is today much better known and more widely practiced. As the Harvard professor Diana Eck, an expert on contemporary American religions, declared in 1993, “Buddhism is now an American religion.”

Professor Eck observed that Buddhists have been in America since around 1850, and their numbers have increased greatly over time. Surveys indicate that today over 30 million people, or close to one-tenth of the US population, identify themselves as Buddhist; read and engage in Buddhist spirituality but don’t identify themselves as members of a religion; or have been strongly influenced by Buddhism. Which taken together means that Buddhism is, whether in numbers or influence, one of the fastest-growing religions in America.

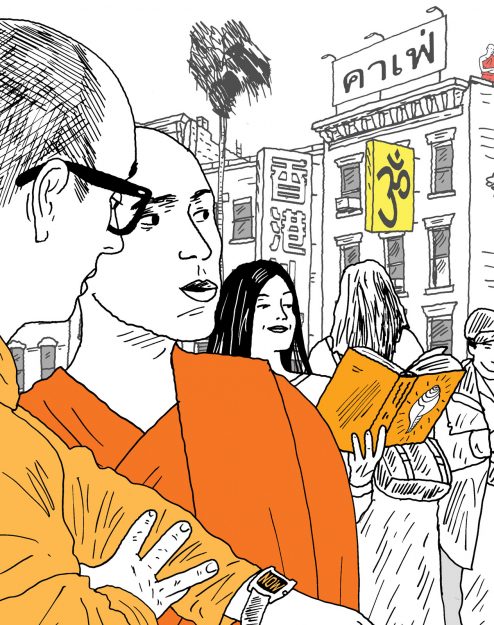

While the vast majority of the approximately 500 million Buddhists in the world live in Asia, one fascinating aspect of Buddhism in America is that, for the first time in nearly the entire 2,600 years of Buddhism’s history, all the major Buddhist denominations in the world today coexist in one country. In many large American (and Canadian) cities there are more different kinds of Buddhism than are found anywhere in Asia, including Bangkok, Taipei, Seoul, and Kyoto. In the Los Angeles area, for example, close to 100 different Buddhist traditions—representing virtually all the world’s main denominations—find a home. Whereas in Asia, Buddhists from different countries have rarely known, or even known of, each other, in Los Angeles you may find temples with roots in Thailand, Korea, and Vietnam located near each other, sometimes even on the same street. For me, this trend provides a new and exciting opportunity for all Buddhists to learn from and better understand each other.

Despite the promising demographics, and despite Buddhism’s high level of cultural visibility and accessibility, few introductory books seem to address youths and young adults. Having been myself an American Buddhist youth, and having raised three young Buddhists as well, I had long felt there was a need for easy-to-understand introductory books for this audience. And so a few years ago I set about writing one. The book, Jewels, was published in the spring of 2020. After its release, a friend pointed out that because American Buddhism includes so many different communities, the book might also be of value to Buddhists who know a great deal about their particular corner of American Buddhism but not much about its full range. It is with this in mind that I’ve adapted sections of the book for this article.

In America, for the first time in nearly 2,600 years, all the major Buddhist denominations in the world today coexist in one country.

I chose Jewels as the title of the book because in Buddhism jewels are used as a metaphor for something of immense spiritual preciousness. A person is considered to have become a Buddhist when they accept as the basic foundation of their life the “three jewels,” referring to the Buddha (the fully awakened person), the dharma (the Buddhist teachings), and the sangha (the community of fellow Buddhists). For Buddhists of all schools, the three jewels are the object of ultimate reliance and respect. This imagery of jewels also can help explain how these divergent schools can live in harmony.

Buddhist teachings tell us to see all living beings as precious jewels. You and I, along with all beings, are like jewels that are linked together in the vast web of the universe, each jewel reflecting all the others. Each jewel has an outer and inner aspect.

The outer jewels are talked about through the metaphor of Indra’s Net of Jewels. Indra’s net is known in East Asia through the teachings of the Huayen school of Buddhism, which is based on the Flower Garland Sutra and related writings. The metaphor is now often cited by Buddhists in North America and beyond.

Picture an expansive net extending endlessly in all directions throughout the universe. At each of its nodes hangs a shimmering jewel. Each jewel is connected to all the other jewels, even to those so distant that they are not even visible from one location.No jewel shines by itself. Each one needs the light from the other jewels to shine. At the same time, a jewel does not just receive light; it also gives out light. Although each jewel may illuminate nearby jewels with greater intensity than it does distant ones, each shines on all the others, no matter how faintly. They need each other and help each other. They are mutually linked, interconnected, and interdependent.

No two jewels are exactly the same. Despite being countless in number, each jewel is unique in its shape, size, color, and texture. Each of us is one of these jewels. We are dependent on others, yet we also contribute to others. Such is the nature of our existence, which includes our relationships with our family, our friends, our community, the nation, the international community, and the natural world. Each jewel has worth and value simply for existing and for being a part of this net of jewels.

As one of the jewels in the web, I am connected to the countless other jewels that illuminate and support me. This is the outer jewel. At the same time, there lies within each one of us an inner jewel, waiting to shine forth to help us realize Buddhism’s aim of awakening, overcoming suffering and manifesting joy, satisfaction, peace of mind, and gratitude—its aim, in other words, of achieving happiness.

To understand the inner aspect of the jewels, we can turn to a famous parable from another important Buddhist scripture,the Lotus Sutra. The parable tells of a poor man who visited the house of a rich friend, where he was wined and dined. The poor man got drunk and fell asleep. While his friend slept, the rich man sewed a priceless jewel into the lining of his poor friend’s clothes. The poor man awoke and set out on a long journey, unaware of the jewel he now carried. One day, by chance, the poor man ran into his rich friend, who saw that his friend’s life continued to be so hard and realized he hadn’t discovered the jewel. When the rich man told his friend, the poor man was overjoyed. He had discovered at last that precious something that had all along been in his possession.

The jewel, of course, symbolizes our spiritual potential to become happier and wiser. We all have that inner jewel, and the teachings of the Buddha are meant to help us discover that for ourselves. Our task is to take hold of that jewel, polish it, and let it shine forth.

All Buddhist schools teach the path to awakening, seeing that we are all jewels. But different traditions present the teachings differently. In America, where there are so many denominations, it can be hard to gain a full picture of what American Buddhism even looks like. To help understand this, I find it useful to categorize the various kinds of Buddhism into four main groups.

The first group consists of older Asian American Buddhist communities. They started their temples in the mid to late 1800s and are mostly of Chinese and Japanese origin. Today, because they are mostly third-, fourth- and fifth-generation Americans, their temple activities and services are held in English.

Since the mid 1960s, newer Asian American Buddhist communities have formed in the United States as more people have immigrated from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, and elsewhere. Because these communities still have a large percentage of first-generation members, temple activities and services are often held in their respective native languages. However, English is being used with increasing frequency as the second and third generations come of age. For newer and older Asian American Buddhist communities alike, temples serve as hubs for both religious and cultural life.

The next group consists of those who were for the most part not born into Buddhist families but converted to Buddhism as adults and whose main practice is sitting meditation. They are predominately of European descent, though there is a substantial and increasing membership of people of color. In general terms, members of this third group belong to Zen, Theravada (particularly vipassana, or insight lineages), or Tibetan traditions, which are centered on meditation practices. The immense popularity over the past decade or so of mindfulness practices has definitely increased the numbers belonging to this group.

The fourth group is made up of convert Buddhists whose main practice is chanting. The majority of this group are affiliated with Soka Gakkai International, or SGI, which is a denomination of Nichiren Buddhism. Like that of other Nichiren Buddhists, the main practice is reciting the Odaimoku, “the great sacred title” of the Lotus Sutra, which in SGI is pronounced “Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.” One of the largest Buddhist organizations in America today, SGI is also the most racially diverse organization, with a membership that includes large numbers of Asian American, Latino, African American, and white participants.

We might understand the rapid growth of American Buddhism by borrowing from economics the concept of supply and demand. “Demand” here refers to those factors that “pulled” or “welcomed” Buddhism. Several stand out: First, Americans value religion to a much greater degree than do people in most other developed countries. Religion tends to be seen as a “good thing,” providing a spiritual and ethical foundation for living. This is especially apparent in the raising of children. Also, Americans tend to hold pastors, priests, rabbis, and other religious professionals in high regard. Religious leaders often serve as leaders in the general community beyond their particular churches, mosques, temples, or synagogues. The value we place on religion is so much a part of American society that we often take it for granted and scarcely notice it.

A second “demand” factor is societal openness. In the 1960s, American society’s attitude began to shift toward greater openness toward religions other than Protestantism. For example, when John F. Kennedy campaigned for president in 1960, suspicion about his being Catholic was the cause of significant opposition. But in 2020, President Joe Biden’s Catholicism was most often seen as a strength because it signaled that he is a person of sincere religious conviction, regardless of sect.

Changes in immigration laws in 1965 further fostered religious diversity, and thus openness, because of the arrival of more people from non-Western countries, including Buddhist immigrants from Asia.

Within this atmosphere of openness, Buddhism has come to be seen less as a weird “Oriental” cult, as it was when I was growing up. In fact, as the number of people interested in spiritual matters increased, it was often thought, however naively, that “spiritual Asia” was superior to the “materialistic West.” Many such people were attracted to Buddhism because they found in it a response to the spiritual needs of an industrialized culture.

The third factor follows on this, and it has to do with change in the very nature of religion in America. Surveys have shown that Americans have in increasing numbers become more attracted to spirituality than to what is often called “organized religion,” meaning religion as centered on membership in institutions such as synagogues, temples, and mosques. The phrase “spiritual but not religious” is often used to describe such people.

In addressing the spiritual needs of so many, Buddhism has become a diverse and multifaceted part of the American religious landscape.

Turning to the supply side of Buddhism, we can identify certain qualities that have appealed to the spiritual and religious needs of Americans. In particular, Buddhism fits in with the trend of valuing a spirituality that stresses personal experience. That is, you could say, Buddhist teachings show us that we have been carrying around a precious jewel all along.

One such quality that Buddhism offers is its attitude toward the suffering we all deal with in facing life’s difficulties. Buddhism sees difficulties such as sickness, loss, disappointment, and death as a natural part of life and not something to try to deny. Suffering is something that needs to be understood, accepted, and turned into a springboard for living a fuller and more meaningful life.

Second, Buddhism seeks to speak to the unique experience of each individual. (After all, no two jewels are the same.) Because of this, it can be a valuable path to self-understanding. Many Americans like to feel that they are free to question religious teachings and to make up their own minds about them, and Buddhism not only allows for this but even encourages it. This is the reason for the popularity of the Kalama Sutta, in which the Buddha says:

Don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical conjecture, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought, “This contemplative is our teacher.” When you know for yourselves that, “These qualities are skillful; these qualities are blameless; these qualities are praised by the wise; these qualities, when adopted and carried out, lead to welfare and to happiness”—then you should enter and remain in them.

–Anguttara Nikaya 3.66, trans. Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Probably the number one reason for the growth of American Buddhism is found in the popularity of meditation. This third aspect offered by Buddhism includes practices that many find easy to learn, mentally therapeutic, and spiritually empowering and liberating. Sitting meditation as taught in the Zen, Theravada, and Tibetan schools has been especially attractive to converts.

The American sociologist of religion Wade Clark Roof describes spirituality as “personal experience tailored to the individual’s own quests.” Spirituality, he writes, is associated with five key terms: connectedness, unity, peace, harmony, and centeredness. Buddhism as presented in America attracts people looking to experience these qualities in their lives. In addressing the spiritual needs of so many, Buddhism has become a demographically diverse and multifaceted part of the American religious landscape. To me, this is very exciting.

Like the jewels in Indra’s net, each community, each lineage shines a light on the rest, each helping and being helped by the others to glow brighter.