Every Wednesday morning when I can afford the time, I park at the foot of the valley I live in and climb Mount Tamalpais, my holy mountain. It is more sacred to me than any temple, and as powerful a place of practice.

My path is as ritualized as the stations of the cross. I take a wooden footbridge over a stream and climb through second-growth redwoods and past blackberry bushes, now sere and brown in the winter cold. My worries come with me: I chew on a conflict with my eighty-year-old mother, a disastrous visit home.

I climb steep railroad-tie steps to Cowboy Rock. My glutes and lungs burn, driving me into my body. I pant. I sweat. I take off my fisherman’s knit sweater, machine-loomed in England and bought at a local mall. Then up past the county water-tank and the dozen expensive houses built where the Flying Y Ranch used to be.

At ten o’clock, I breach a ridge and enter a vast bowl of unpopulated hills. Car sounds die away. Finches twitter in the chaparral. I follow the trail beneath a bay laurel, upswept by the winds into a clinging topiary. A madrone shows its red bones. “Mountains,” the Zen master Eihei Dogen told an assembly of Japanese monks in 1240, “are our Buddha ancestors”—our primordial teachers. Inside my brain, an invisible hand turns the volume knob down.

Now I am moving deep into the sock of the valley—the only visible human. Except for a ribbon of yellow-lined asphalt below me, there is no sign of human making. Beyond the last hills lies the Pacific.

An hour later I round a ridge and the peak of the mountain reveals herself, rising. I remember Mirabai, the sixteenth-century devotional poet who abandoned her aristocratic family and wandered India, singing, “I worship the mountain energy night and day.” The trail switchbacks take me down deeper. An hour after noon, I stop at a flat, thick wooden bench in a grove of old-growth redwoods that the loggers left behind. Here I sit zazen, robed in silence and filtered brown light. The natural world restores my soul. It soothes me like a mother. I rest my head on it and lay my burdens down before it the way some Christians rest their heads on the cross.

California is not my native home. I was raised in Oxford when England was recovering from the Second World War. The country had been a coal-burning industrial power for more than a century, but compared to the way Americans live today, we lived almost as frugally as Thoreau at Walden Pond.

Eggs and butter and meat were rationed. Shoes were polished and repaired. A big black dray horse named Flower clopped down our street twice a week, pulling a cart from which my mother chose vegetables to cook with dinner. Our cramped brick row house had no central heating, and white furry mold grew up the walls of the cellar. People took buses or walked everywhere. Even after our family bought a car, my father was one of thousands who mounted bicycles and flooded the city at rush hour like swarming bees.

My mother, who had no outside job, knitted sweaters and darned socks in the evenings before the fire. She had a washing machine but no dryer. Before she hung the laundry up to dry, she cranked it through the rollers of a mangle to squeeze the water out. Nobody called her “ecological” or understood that her daily work was an expression of respect for the natural world. But she was as frugal and attentive as the cook in a Zen monastery. One of her favorite phrases was “elbow grease.”

One day when I was very young, she stopped the car on a road through a great beech woods. It was autumn. All the leaves were golden yellow. The branches of the beeches met high above our heads, making an arched and open cathedral. The very air was yellow with the glory of the trees.

My mother turned off the ignition and put the keys in her pocket.

“We are going to build a house for the fairies,” she said, and opened the door. We walked into the glowing woods. At a hollow place at the foot of a tree, my mother knelt down. She brushed away leaves and stuck forked twigs into the ground. She balanced sticks across the clefts, making roof-beams, a ridgepole, then rafters. I propped beech leaves against the sides and set them along the roof— they were broad-bladed, like flattened spears, and their points made a jagged line along the peak. We put moss in the front garden, and round white stones to lead the fairies to the door. My mother was an agnostic, a rebel, and a lover of modern architecture. She had nothing good to say about reverence. But that day she led me to something she could not give me and built something close to an altar.

My parents were nominally Anglicans, and on Sundays, when I grew older, they sent my brothers and me to the church of St. Michael

and All Angels. There, in the basement Sunday school, I glued images of martyred saints onto cardboard. I was told that God was everywhere and saw everything, and I imagined him as a series of transparent shower curtains embedded with multitudinous fish eyes, moving in every wind.

At night, I’d kneel by my bed and beg for a sign of His reality. But God was silent—at least in the forms that I expected Him to speak – until Saturday, when I would ride my bike to green fields bordering a stream and lie face down in the mossy grass, letting the green energy rise up into me.

There, I had an inkling of a wholeness beyond the logic of my family. I didn’t have to work for it. All I had to do was put myself in a position to receive. Green things continued to feed what I call my soul long after I abandoned hope of ever seeing the luminous fish eyes of God waving in the transparent wind. I worshiped holy water and holy dirt long before I called it prayer.

When I was eight, my family moved to America and my parents built a Bauhaus-inspired four-bedroom house overlooking a lake in the suburbs of Boston. America amazed us: the supermarkets, with row on row of perfect, pesticide-kissed fruit; the oil furnaces in the basements of big houses, blasting hot air into every room; the ice cream parlors with their banana splits and three-scoop ice cream sundaes; the giant milk-fed children; the enormous superhighways and big cars—all summing up what my mother called America’s “higher standard of living.”

In due course my father got a better job and a bigger house and our family acquired many little machines: a television, station wagon, lawnmower, second car, blender, coffee grinder, microwave, rice cooker, toaster oven, hairdryer, air conditioner. Friends of my parents moved into a new development where clotheslines were forbidden.

We didn’t think we were trying to satisfy endless craving. We didn’t see a connection between what we bought and the destruction of wild places we loved. We just wanted to be warm, safe, fed, and comfortable. We did not know that something in the human brain never hears or whispers “enough.” We were part of a liberal, affluent society that believed that “the greatest good for the greatest number” was mathematically translatable into “the greatest number of goods for the greatest number.”

We knew nothing of Buddhism. We’d never heard of a then-obscure British economist named Ernest Friedrich Schumacher, who, in a 1966 essay called “Buddhist Economics,” suggested another path, especially for developing nations: the greatest possible human enjoyment from the smallest quantity of goods.

The Buddhist ethos of right livelihood, E. F. Schumacher argued, could be extended to an ethos of right consumption. He argued against elaborately sewn, soon-to-be-outmoded suits and in favor of the loosely draped medieval robes of the monk—always in fashion! No ascetic, he argued for a middle way in material matters—in favor of enjoyment and against craving. Happiness, his work suggested, was not typified by the ice cream sundae wolfed down alone in front of the television, but by a cookie and a cup of green tea, brewed in awareness and sipped at leisure with friends, while watching the rising moon.

When I was twenty-eight and working as a newspaper reporter in San Francisco, my roommate and I went on a camping trip in the Ventana wilderness inland from Big Sur. On a whim, we drove down a long dirt road to a hot springs resort deep in a knifelike canyon in the Santa Lucia mountains. The place turned out to be Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, and by chance I ran into an old San Francisco friend who had become a resident there. He arranged a cabin where we could spend the night, and the next morning before dawn he led me to the zendo.

Two and a half hours later, I came out into an early morning light in a state of clarity I’d never before known. Something I had not known was still alive inside me had been listened to, and I had faith that it would someday find its voice. I spent the whole of the next summer there.

As we walked up and down the canyon to clean cabins, chop vegetables, light kerosene lamps, and sit in the airy wooden zendo, we were soaked in the natural world. Crickets, streams, silence, and the rising force of the surrounding mountains permeated everything we did. I still wonder if Buddhism would have grabbed me the way it did if I’d first encountered it in a city.

One morning in the zendo I saw a lizard crawling along the shoulder of a man’s black robe. Another evening in the zendo, we prostrated ourselves over and over in the Full Moon Ceremony, and I climbed a hillside afterward in the astonishingly bright light of the full moon.

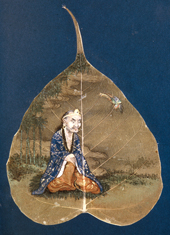

In the library, I came across Dogen, who brought an invigorated form of Ch’an (Zen) from China to Japan in the thirteenth century. His work was dappled with natural images: the moon flooding the water with light; a water bird paddling and leaving no trace; a vegetable leaf transformed into the golden body of a Buddha; mountains flowing, mountains walking, mountains traveling on water. “The color of the mountains is Buddha’s body,” he wrote. “The sound of flowing water is his great speech.”

The Christian theology I’d been raised in had posited a hierarchical “great chain of being” with God on top, humans in the middle, and all other creatures and plants arrayed systematically below. Dogen suggested a radically democratic “flow of being” in which we humans could be instructed by the ten thousand interpenetrating and flowering things of the natural world. In Dogen’s view, each thing flowed without effort from form to form: from cloud to rain to stream to cloud and back again; from corpse to rot to compost to earth to flower. These were not metaphors for transience, reincarnation, no-self and interdependence, but manifestations of them.

“Walls and fences cannot instruct the grasses and trees to actualize spring,” Dogen wrote. “Yet they reveal the spiritual without intention, just by being what they are. So too with mountains, rivers, sun, moon, and stars.”

When the summer was over, I drove back to the city and started meditating each morning in a basement zendo near the freeway. I spent hours each day meeting deadlines on a computer under fluorescent lights downtown. Something wordless that had risen up in me in nature—a yearning for beauty and an ecstatic gratitude for life—had helped pull me back into religious life and into a new religion. Now I lost touch with it again. I saw no connection between the awe I’d felt in the mountains surrounding Tassajara and the chanting and bowing I did in an urban Buddha hall each morning.

Awe seemed out of place in my city practice and city life. A fellow student told me he saw Buddhism as a philosophy and a practice, not a religion. He couldn’t understand why we bowed at all. Like many of the people I knew who practiced within the Vipassana tradition, he wanted simply to count the breaths, sweep the body, examine the workings of the mind, and practice walking meditation. His strain of American Buddhism, growing within a secular, consumerist urban culture, seemed rationalized, almost denatured, spun clean in a centrifuge. I kept hiking and meditating, but saw only my meditation as a form of practice.

Like Christianity, Buddhism is one of the great abstract second-generation world religions. Its overarching principles are universal and portable, not bound to culture or place. But in place after place, both Christianity and Buddhism have been enriched by animism’s fertile, complicating stains. In Europe, Christian holy days were pegged to pagan festivals that brought a ragged joy into a religion flavored with self-denial; churches were built at the sites of wells and hills sacred to indigenous religions. Likewise, nature worship permeated Asian cultures before the Buddha was born.

Natural images abound in the early Buddhist sutras: Shakyamuni was born under a tree; he awakened on a cushion of buffalo grass in the light of the morning star; he touched the earth in response to the temptations of Mara; and he held up an Udambara flower to enlighten his disciple Ananda. He delighted over the beauty of the rice fields. He told his monks to meditate at the foot of trees. A decade ago, I went on a tour of Japanese temples as a travel writer for Vogue. Signs of Shinto nature worship were everywhere. In fields, folded white papers hung on shocks of rice to draw the attention of nature spirits. In the mountains, I walked under torii gates to a clearing in a cedar grove and found a small altar hung with red lanterns and guarded by two stone foxes. The trunks of cedars rose, as smooth as masts, far above my head, and then opened into a canopy of feathery branches. I was standing at the bottom of a hundred-foot-high column of filtered light. The shrine did not create the sacredness of the place, but simply drew attention to it.

This was my wordless introduction to folk Shinto, Japan’s indigenous, pre-Buddhist religion. It has no founder, no dogma, and no scriptures—just rituals tied to the natural world. It honors a world spontaneously brought into being by the hard-to-translate kami— spirits of nature embodied and embedded in everything beautiful and therefore sacred: a rock, a lightning bolt, a waterfall, a grove.

“Do not be attracted by the sounds of spring or take pleasure in seeing a spring garden,” Dogen told his disciples in thirteenth-century Japan. “When you see autumn colors, do not be partial to them. You should allow the four seasons to advance in one viewing and see an ounce and a pound with an equal eye.” But outside his monastery gates, rice farmers were welcoming the spring with Shinto festivals and giving thanks for the harvest in autumn, knowing full well that the seasons would turn and come again. I picked up a broom, entered the little enclosure, and swept the shrine free of fallen leaves.

A few days later, in the mountains near Yoshino, I watched two young monks chant the Heart Sutra in a small temple built over a stream. They were followers of an ascetic and syncretic Shinto-Buddhist mountain tradition called Shugendo, which venerates snakes and waterfalls as well as buddhas and bodhisattvas. Blowing on conch shells, they exited the temple and walked up a series of stone steps, bowing at dozens of small altars. They bowed equally to peaceful stone bodhisattvas lined against a rock face running with water, and to a huge dragon-headed metal snake twined around a Shinto spear. I followed them, bowing, the two halves of my religious life finally coming together.

It is usually three or four in the afternoon when I retrace my way off the mountain, leaving the redwood grove and moving through bays and grasslands, passing a red-tailed hawk swooping across the bowl of the hills. Car sounds return. I descend past the rich houses of Flying Y Ranch and Cowboy Rock, into the valley of my daily life. I put my sweater back on, and start thinking about dinner. I start the car and drive home, to our dishwasher, coffee grinder, microwave, computers, and panoply of electric lights. The joy of my day on the mountain has fueled my efforts to live a saner life. It somehow helps me meditate for the rest of the week.

At home, I pick up the phone, call my mother, and reconcile. Then I take Dogen down from my bedroom bookshelf and read “Instructions to the Tenzo,” a practical guide for the head cook at a Zen monastery. Its severe tone seems at first to have little in common with the mysticism of his Mountains and Waters Sutra. Lose not a grain of rice, he says. Take care of the monastery’s rice and vegetables “as though they were your own eyeballs.” And when you boil rice, “know that the water is your own life.”

I try to obey. At dinner, I put the newspaper aside, light candles, and eat with full attention. “Innumerable labors brought us this food,” goes the meal verse we chanted at Tassajara. “We should know how it comes to us.” I try to remember where everything I use comes from and where it is going. I feel a mixture of guilt and gratitude. I try to regard every thing I handle—my rice, my sweater, my vacuum cleaner—as if they were my own eyeballs.

I blow out the candles. I clean the table and stove using super-cleaning microfiber cloths that require only hot water rather than chemicals. I apply elbow grease.

These forms of attention are more mundane and difficult for me to practice than the ecstasy I often feel on the mountain. Yet they too express a reverence for the natural world and an understanding of interdependence, just as my mother did when she squeezed water out of her laundry in England, and as Mirabai did when she worshiped the mountain energy night and day. Ultimately, Dogen says, housewifery and ecstasy are not that different. “Taking up a green vegetable, turn it into a sixteen-foot golden body,” he challenges me.

My altar holds not only a Buddha, but a seashell, a metal cricket, a snake, and an image of Mary. Likewise, my religious practice now is a hodgepodge of nature worship and Buddhist meditation and twelve-step programs, and I cannot make it all sound logical or consistent. When I’m tired or lonely and want to be numb, you can often find me driving alone up Highway 101, feeding the hunger that isn’t hunger, stopping at Whole Foods and Costco and Trader Joe’s, loading up on Brazilian papayas and toilet paper from the forests of the Northwest and my favorite yogurt from Greece. Sometimes I think I’m in the realm of the gods when in reality I’m acting like a hungry ghost. I forget that there is something in the brain that never hears “enough.”

Yet I don’t want to become so ascetic, taking no pleasure in a spring garden, but rather to open my heart and my senses to the vivid love I have for the natural world. The paradox is that when I open myself fully to pleasure, I use and waste less.

The next morning at breakfast, I light the candles, bow over my food and chant. I eat a bowl of oatmeal and half a papaya with a squeeze of lime. I dig the spoon into a bowl of smooth Greek yogurt. I let it roll off my tongue. It is not only asceticism that will save us, but delight. All the universe is one bright pearl, wrote Dogen. Everything is holy.

Wilderness Journey

“I found myself in a workshop one day talking about Zen and the environment,” says John Daido Loori, abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, “and I realized how stupid it was because, you know, Zen is very experiential. You don’t talk about it. You do it. So I decided I should take these people, most of whom had never been in the wilderness, out into the wilderness and let them experience it for themselves.”

That first canoe trip, a grueling 125-mile cross-country jaunt, was so successful and generated so much excitement that Loori and the monastery developed an array of programs and workshops known collectively as the Born as the Earth program, Each uses the wilderness experience and the natural environment to teach the interdependency of the self and the universe, and outdoors skills and knowledge to overcome feelings of fear or anxiety about being out in the wilds.

Founded by Loori in 1980 in the tradition of the Mountains and Rivers order of Zen Buddhism, Zen Mountain Monastery sits on a 240-acre parcel of land in the Catskill Forest Preserve. In its first meeting, the monastery board designated 80 percent of its land to be forever wild. “If a tree falls,” says Loori, “it rots where it falls.”

Established as a contemplative retreat, the monastery was jolted into environmental activism when the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation attempted to appropriate five acres of its land under eminent domain in the early nineties. The monastery decided to resist and found several environmental lawyers, field biologists, and ecologists among the alumni of the Born as the Earth programs willing to take on the DEC. They formed the Green Dragon Society under the auspices of a new nonprofit corporation called the Zen Environmental Studies Institute (ZESI) and won the case. The society is currently involved in a class action suit along with twelve other environmental groups to halt the development of a resort on Bellair Mountain, in the Catskill Forest.

All of these activities are based on a conviction that love of nature is a far more powerful force in protecting the natural environment than science, legislation, religion, or self-interest.

As the ZESI brochure points out, ”We take care of the things we love.”

—James Keough

For more information, contact Zen Environmental Studies Institute. PO. Box 24, Mt. Tremper, NY 12457; (845) 688-7240; www.mro.org/eco.