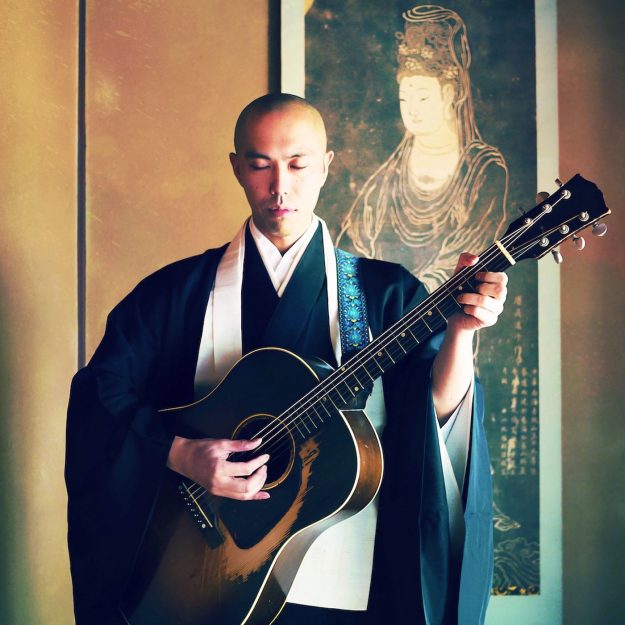

Almost five years ago, a video of monk and musician Kanho Yakushiji singing the Heart Sutra went viral. Yakushiji arranged a chorus of voices on top of the scripture, one of the most popular sutras, and when the video of his live performance was uploaded to the Web, millions of people watched, shared, and reposted.

Like the audience, who clearly felt the aliveness of this Zen Buddhist text that is chanted every day around the world, I was so moved by the soulfulness of this monk.

Yakushiji serves as deputy director of Kaizenji temple in Imabari, a city in Japan’s Ehime Prefecture. Japan has a strong tradition of danka, or the father-to-son succession of a temple, but Yakushiji initially rebelled against this expectation and instead became a musician. He eventually trained in the Rinzai tradition at Kenninji temple in Kyoto, Japan, and is now the sixteenth generation of his family to care for Kaizenji.

Though he initially thought about music and Buddhism as separate entities, Yakushiji now views music as an expression of Zen practice. His two identities—a Zen monk and an artist—are no longer separate. He released his fifth album, The Prayer, in September of 2019, and just before the pandemic began, he started a music video project whereby he chants in historic Japanese temples to introduce listeners around the world to Zen and chanting. Now that international travel is restricted, the project has taken on a new meaning. I spoke with Yakushiji about his music, Zen training, and how he brought these passions together.

When did you realize you had a talent for music? My father also loves music and I became interested in music because of him. He took me to karaoke when I was little, and we used to listen to records together. He liked guitar as a hobby but didn’t play well. I started playing his guitar when I was in junior high school. And I used to chant the Heart Sutra every morning before going to school.

How do you reconcile the tension between tradition and innovation? I believe [that both] keeping the tradition and change are necessary. Arranging the sutra as music means “change.” Not everyone approves, but I believe change is necessary to remain with the times and give a new generation a chance to learn about Buddhism.

Who introduced you to soul music? It was my voice teacher and singer, the late Mr. Dainoshin Watanabe, who taught me to sing with soul and to enjoy music wholeheartedly. Until I met him, attending a voice lesson in Kyoto, I was listening only to rock. When I first heard soul music, I realized that I wanted to be able to sing emotionally like that.

Watanabe taught me to feel the rhythm in my body and sing, so I would sing while keeping my body moving to the rhythm. Since it’s not easy to sing emotionally from the beginning, it helped to first let my body feel the rhythm and be in a neutral state before singing. I learned to grasp the music in new ways, [tuning into] rhythm and breathing speed, instead of simply following the melody. [From then on,] I started to sing with the goal of being one with the music.

When did you go back to train in the monastery? When I was 27 years old, Kissaquo [the band I formed as a student] debuted on a major record label. It was then that we hit the biggest wall. When we were starting out, we worked extremely hard and did everything on our own, but the environment suddenly changed and we had to engage with many people in order to create music. Many people had many opinions about us. I no longer knew what I wanted to convey through my music, what was right, or what I wanted to do. I even started to dislike singing. When I stopped to pause, something drew me to read Buddhist books.

The decisive moment came following a concert on the island of Kyushu. An old man approached the table where my bandmates and I were signing autographs, and his eyes were filled with tears. “Tonight I heard a song that reminded me of when I was a boy,” the old man said. “Like you, I had wonderful grandparents who helped raise me. I miss them, but your song reminded me of those happy times and I thank you.” I remember, you remember. Suddenly, the space between the past and the future, my paths as a monk and as a musician, duty and desire, weren’t quite so far apart. I realized all is one. It wasn’t until then that I saw how singing and Buddhism may be similar. The interaction inspired me to write my most personal song called “I Am”:

Who am I?

Laugh Laugh

I’m strong

Is that me?

Told at the reunion

“It won’t change”

No, no, not really

You just don’t know

In the mirror, I’m at the end

I have no choice but to live in the present

While telling

The tears that overflowed

I tried my best to laugh

Everyone has a secret

Trick, hurt, hurt

Even if it’s hard to look back

The past hasn’t changed

Just straight to that fate

Don’t take your eyes off

In the eyes, beyond the darkness that spreads

Project that day

The dreams and memories that were thrown away on the way

Collect

I’m sure I will live there now

Because there should be an answer

I’m here now

my everything

Hesitation

It’s natural that there’s a human being

Things that change over time

No need to divide

Take all

Live the present now

Only one person

Only one

Only one

I’m “I”

After writing these lyrics, my heart was refreshed. For the first time, I considered becoming a monk and decided I would begin my training. At last, the path had revealed itself. My childhood in the temple had taught me that the sacrifice and hardship of entering the monastery would be considerable, but when the way is illuminated, I knew to follow. I decided to face myself and train as a Buddhist monk in 2010.

I spent two years of my training living a traditional life centered on zazen [seated meditation]. I spent my days cleaning, growing vegetables, doing alms-gathering, and practicing zazen. I struggled for the first three months of the training and did not have any breathing space until I got used to this new way of life in the monastery.

After about three months, I began to experience sensations and moments of beauty that I had never felt before. Once, when I was outside doing zazen, I saw a spray of water illuminated in the sunlight. The subtle shadow and movement of the water made me suddenly understand time—it was a feeling of movement. The state of enlightenment was still a long way off, but at that moment I could see my heart a little. I realized then how my mind was always buried in something and it prevented me from clearly seeing my mind. I think that by being separated from the things that were always around me and by integrating movement and mind through zazen and samu [mindful physical work] in my training, my mind started to be clear.

How did it feel learning to chant sutras in the monastery? I learned the sutras that are regularly read in Rinzai-shu [Rinzai Zen Buddhism], such as the Heart Sutra, Daihisin Dharani, and Avalokitesvara sutra. About ten to 20 of us at the training dojo used to chant every morning, and the chorus of the many voices brought emotional and calming sensations to me. At that time, I wondered: What if I arranged a sutra chant musically by layering the chorus?

It felt as if my heart was being supported from the bottom. After chanting, I felt like I could face forward, and my mind was renewed. It occurred to me then that if I arranged the sutra with a layered chorus, I should be able to bring about the same deep emotional feeling.

When did you think to unite your music life and Zen life as one life—wearing koromo, rakusu [monastic robes], and chanting sutra? What shifted in you? Initially I thought about music and Buddhism separately. I started to realize the message of the songs I wrote was connected to Buddhism and the two worlds gradually became one. The major turning point was when I made the musical arrangement of the Heart Sutra in 2016. I realized I didn’t have to separate music and Buddhism anymore, and I came to the conclusion that I should simply convey my message in my own way.

In what ways do you continue to appreciate and practice Zen in the traditional expression? Rinzai-Zen is “koan Zen.” I consider my songs to be my expressions or responses to koans. Everything in our everyday lives is a practice and gives us a koan. My expression of those koans? I write and sing. While my current life is not centered in zazen like when I was in training, I’d like to appreciate and be mindful of every aspect of my daily life.

How is your struggle with the identities of either monk or musician now? I’m not stuck with any one identity anymore. I became a monk who happened to like music. I will just be myself and convey my message.

Throughout the pandemic, you have continued to make videos of you singing the traditional chants of Sesonge, Heart Sutra, and Nilakantha. What do these chants mean to you in the time of COVID-19? I had started this video project before the pandemic. At the time, I never imagined we would be in the situation that we are in today. The pandemic continues. We have lost a lot, and we have also gained a lot. The Sesonge teaches us to nurture our own hearts and minds; the Heart Sutra teaches us to cherish connections; and the Nilakantha Dharani contains the merits of the thousand-armed Kannon [the bodhisattva of compassion].

Currently, the pandemic makes it difficult for people to visit Japan, but I hope that these videos make people feel like they have traveled in Japan and help them feel at ease. In the future, I’m planning to collaborate with traditional Japanese performing artists to introduce Japanese culture from various angles.

How did you decide to gather Zen monks from around the world for your Heart Sutra “Telework video” in the midst of COVID-19? I hope that this video will be sent to the whole world as one of the messages from the monks, and that those who see it will feel calm and feel that they are alive now.

I wanted to share the power of the voice of people and the power of connection with many people.

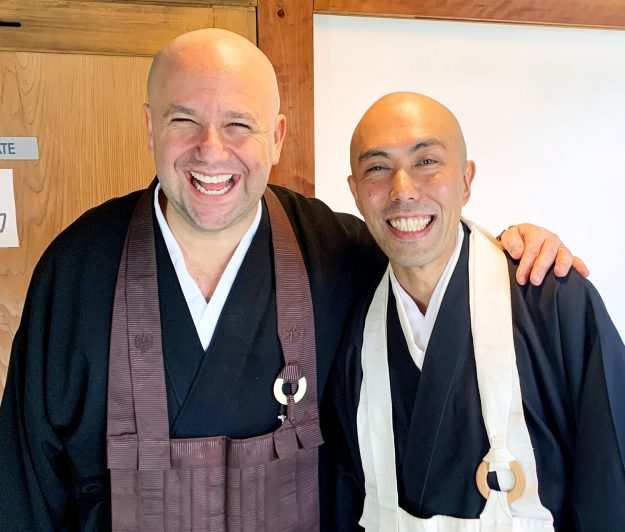

It was after I met you through Instagram and we had a conversation about the documentary about you. Through that, I was connected to people from various countries, and in the end, I was really happy that about 60 monks participated.

You and Chodo-san [the interviewer’s partner, Sensei Robert Chodo Campbell] even participated! I have never met most of the monks who participated. My wish is that we can meet and sing together. That is a dream for me.

♦

This interview, which was conducted in English and Japanese, has been edited for length and clarity. Thank you to Akira Ozawa for his translation support.