The noble words “compassion” and “wisdom” appear everywhere in Buddhist teaching, and they offer us an attractive way of imagining our future selves. We know that when we cultivate our minds, wisdom and compassion will be the result, exactly as they were for the Buddha. Yet this thinking overlooks a key detail. In the days leading up to his enlightenment, Prince Siddhartha would probably have seemed unattractive, even frightening—and the very opposite of noble. Filthy, starving, and alone, he had allowed himself to become completely and abjectly helpless. And here’s the detail that we may overlook: only this condition made it possible for Siddhartha to wake up. Only the experience of helplessness could take him beyond the limits of the self.

Core features of the dharma point to helplessness as the transcendent experience, not as a moral failure, a cause for shame, or a condition to be overcome through heroic feats of self-discipline. I’ll even go so far as to argue here that Buddhism sacralizes helplessness as the place where wisdom and compassion both arise. Not until events escaping their control bring people face-to-face with their helplessness will they discover that they belong to something larger than themselves: an “unlimited body,” in the Lotus Sutra’s words. To find the Buddha’s wisdom is to recognize this shared body as what we really are, while compassion arises when our sense of helplessness moves us to action in the world.

Even though we try to keep it out of view, we encounter helplessness everywhere we turn at each stage of life. As children we rely on our parents’ care, and once we start school we depend on the guidance of our teachers. No matter when our education stops or how many diplomas we hang on the wall, we’ll need other people’s help when we’re looking for a job, scouting out decent childcare, or investigating places to retire. Eventually we’ll have to get an assist crossing the street or rising from a chair. And now, over 16 grueling months, we’ve faced helplessness on a global scale, whether or not we lost our jobs, had to view our mother’s funeral on Zoom, or found a landlord’s padlock on our door.

Yet if you’ve grown up in the United States, you know how people can respond to helplessness—sometimes with sympathy, true enough, but often with anger, disbelief, and, on occasion, even open contempt. I’m sure that many of us fell speechless as we watched the clips of then-candidate Donald Trump belittle a reporter with a disability while a packed stadium cheered him on. Yet Trump was just acting from a cultural script that we may resist but can’t easily ignore. The mass-culture heroes of our time, in the Marvel universe or otherwise, might have their moments of sensitivity and humanizing vacillation, but most of them remain postmodern avatars of long-ago rugged individuals, riding out of town, headed for the hills, or disappearing into history as the smoke of battle clears away.

Their legacy has left us completely unprepared for the complex challenges now described as “existential” because they will decide our common fate. “All in this together” can no longer just apply to the people in your neighborhood or town, for as the panorama keeps widening to take in the entire planet, you and I recede until we seem to disappear among eight billion other human beings. Even the so-called World Wide Web often has a distancing effect, making the centers of authority feel more remote than ever. But here the dharma has a special role to play, because it discovered long ago that the experience of helplessness isn’t the problem we suppose it to be: rather, it’s our hidden common ground and the best hope for the future.

We need, though, to acknowledge from the start that Buddhists themselves have often suppressed this element of their tradition. The World Honored One’s awakening, after all, represents to his followers the pivot point of human history and the supreme achievement of sentient beings. Enjoying a state to which even gods aspire, the Buddha appears to personify everything that anyone might describe as charisma and power. His very name, Siddhartha, which can translate as “He Who Hits the Mark” or “The One Who Gets It Done,” was chosen for him by no less than a king, his father. According to the legend, and to drive the point home, a seer foretold that Siddhartha would become, if not the Buddha of the current age, then the logical second best, a planetary “wheel-turning monarch.” And, as befits a singular event of unsurpassed auspiciousness, the birth of the World Honored One was witnessed by the highest society—as high as the heavens, to be clear; or so we learn from a treasured biography of the One Who Liberates, the Lalitavistara Sutra:

Śakra, Brahmā, the Guardians of the World,

And many other gods stand joyously at [the Buddha’s mother’s side]

Adoring [her] with outstretched arms;

And the Lion of Men, his vows [made previously in Tusita Heaven] fulfilled

Emerges from the right side of his mother

Like a golden mountain;

The Guide of the World emerges in a brilliant light.

—trans. Gwendolyn Bays

While the sala trees burst into bloom, the infant Buddha plants his tiny feet on the surface of the earth. Then, taking seven steps, he declares, “I am the Leader of the World / I am the Guide of the World.”

The Lalitavistara is revered as the dharmic counterpart of the Gospel truth, yet the story makes it hard to imagine how the “Leader of the World” could have experienced anything like the helplessness we’ve known, not just in the COVID emergency but at many moments in recent years. It’s certainly true that once he’s grown, the Buddha leaves the palace and adopts the life of a wandering mendicant, begging for his food, sleeping rough, and clothed in whatever he can salvage from garbage dumps or funeral grounds. Pursuing liberation, he descends from high to low and from worldly power to debility. Indeed, he doesn’t undergo his awakening until his search carries him to the edge of death—helplessness at its most extreme. And we’re told that he might very well have died had he not received a meal of rice and milk from a village girl moved to compassion at the sight of so miserable a derelict, bare-boned, dirty, bleary-eyed. Only then, with his strength renewed, does he resume his vigil and break through.

Yet the sutra never permits us to forget that the Buddha—whom it names the “Conqueror”— remains coolly in control and self-assured. Not for a moment does he go through the wracking uncertainties that haunt us at night, when we worry about how to pay the bills, rescue Grandma from the nursing home, or make up the kids’ lost year of school. Even Mara, the tempter, stands no chance of success launching terrors and seductions to derail the imperturbable prince. To us, the future Buddha may look down and out, but he’s backstopped by cosmic guarantees. The sutra’s Siddhartha already knows that he’s destined to become the One Who Liberates, and he knows, as well, that his challenges actually conspire to ensure his success.

But the disappearance of cosmic guarantees is an essential feature of our lives. While I will attest from my own experience that meditation can take you to a place where, metaphorically, the heavens and the earth meet in your own body, I have to add “metaphorically” because that’s just not our reality now. Some may say that the gods have fled or that enchantment has vanished, while others blame science and secularity, but these explanations assume a deficit where we may also see an enormous gain. If we’ve lost confidence in a heaven looking down on Siddhartha while he sleeps, we’ve also become, in a thousand different ways, more aware of our terrestrial connectedness, along with its liberating possibilities. And in place of the cosmic guarantees that the Buddha in the sutra enjoys, we now have the opportunity to understand helplessness itself as a path to transcendence. It won’t be the transcendence of life’s contingencies, as though we could exist on another plane or shed our humanity, but transcendence through them.

We’re both limited and limitless, isolated and connected in a way the Lalitavistara ignores because its authors want to settle our minds by resolving the tension. In effect, they say to us, “Even if the Buddha’s serenity seems far away from you right now, it’s here and always will be.” This reminder may have the therapeutic effect of helping us forget our afflictions long enough to reach a place of genuine calm. Yet although we can appreciate the sutra’s approach as a form of skillful means, today it might have the very opposite result, making the Buddha’s wisdom appear more remote than ever. There is, though, an alternative to the Lalitavisatara’s strategy: instead of regarding our regret, loss, and abjection as illusions like those conjured up by the demon Mara, we could understand them instead as nothing other than the path. And in that case, our practice will assume a new form we may not yet recognize: accepting everything that happens to us as an opportunity for awakening—and, indeed, as awakening itself.

And this, I would say, is the practice taught by another sutra that enjoys a central place in Mahayana tradition—the Lotus, praised by the great Zhiyi, 6th-century founder of the Chinese Tiantai school, as the last and crowning achievement of the Buddha’s long teaching career. Scholars today have debunked this claim, not only because the sutra first appeared six or seven hundred years after the Buddha died but also because other sutras were composed in the centuries following the Lotus. And yet every time that I’ve returned to it when I’m in the throes of crisis, I’m persuaded once again that Zhiyi must be right in some higher sense. I’d argue that the Lotus Sutra manages to synthesize a deeply moving and humane honesty about the painful situation of the self with the Mahayana view that everything is interconnected. We only feel troubled by our helplessness, the Lotus maintains, because we haven’t become aware of our role in a greater drama.

To that drama the Lotus takes us almost right away, after it has set the scene and introduced the cast of characters. Standing before a throng of followers, the Buddha explains that he has come to reveal a teaching without precedent. In the past, people understood awakening as a special state far removed from the consciousness of women and men caught up in the whirl of everyday affairs. But now he announces a new dispensation. “All of you,” he declares, “will be able to achieve the Buddha way.” And this “all of you” includes everyone: those who won’t rise early to meditate because they don’t like getting out of bed, those lurking in the dark alleys of vice, and even those engaged in the worst of evil deeds. The Buddha affirms that he’ll see them through irrespective of their abilities, their karmic debts, and even their indifference to their own salvation.

The sutra also relates that some in the audience who have made every sacrifice—senior monks, nuns, and laypeople—simply can’t believe their ears. The new dispensation enrages them because it gives the first prize away to all contestants indiscriminately. But beyond that, it completely overturns their view of awakening as a personal accomplishment setting them apart from common ignorance. Because they’ve cordoned off their own minds, they’ve achieved an imperturbability that resembles the Buddha’s. But true enlightenment would let everything in— everything and everyone. Shaking their heads with an emphatic “No,” they rise together and depart.

Yet that’s not how everyone responds, especially, in a shocking turnaround, the bodhisattva Shariputra. Revered from the dharma’s early days as the most accomplished of the Buddha’s followers, he by rights should have been the first to leave. Instead, he can’t contain his happiness after he receives the news—and for a reason no one would suspect. He discloses his long struggle with a secret guilt arising from his failure to live up to Buddha’s high mark. He has observed each precept impeccably and even reached the stage that qualifies as “unsurpassed enlightenment.” Yet his attainment still feels incomplete, and he confesses to “doubts” and “regrets” that cause him to “to spend whole days and nights” in a vicious circle of self-blaming:

Having already freed myself of fault,

Hearing this, I am [now] also free from anxiety.

Whether in a mountain valley

Or under the trees in a forest,

Whether sitting or walking around,

I always thought about this matter

And blamed myself completely, thinking:

Why have I cheated myself so?

—trans. Gene Reeves

Whether or not we aspire to complete enlightenment or even imagine it is possible, every one of us harbors some regrets like those Shariputra voices here, and that’s why it may help to understand the nature of the promise the Buddha makes to him. The Buddha doesn’t say, as readers might expect, “Cheer up, Shariputra, you’re already there!” or “Awakening is just a breath away!” Instead, he affirms the very opposite: “Shariputra, in a future life, after innumerable, unlimited, and inconceivable eons, when you have served some ten million billion buddhas, maintained the true dharma, and perfected the way of bodhisattva practice, you will be able to become a buddha whose name is Flower Light Tathagata.” Complete enlightenment, in other words, lies a long way off.

At first we might find it hard to appreciate why this information would send a dejected Shariputra into ecstasies of joy, but the Buddha asks him, in effect, to stop thinking so obsessively about his personal defects and turn to the encompassing vastness. And if Shariputra shifts perspective this way, the Buddha feels confident that he’ll perceive there has never been such a thing as “individual enlightenment.” Enlightenment isn’t something you and I can earn like a black belt in karate or a Best Film Award; it’s a process, always unfolding everywhere, that involves us all. As the Lotus tries to show, the whole universe is working toward awakening, although its progress can be hard to discern because of the enormous scale and sweep of time required for all sentient beings to plug in—“innumerable, unlimited, and inconceivable eons.” But it’s going to happen, the Buddha maintains. Awakening is so intrinsic to consciousness that even our worst failures and misdeeds point us in the right direction. Sooner or later we’ll all figure it out, like Phil the weatherman in Groundhog Day, but multiplied by millions on millions.

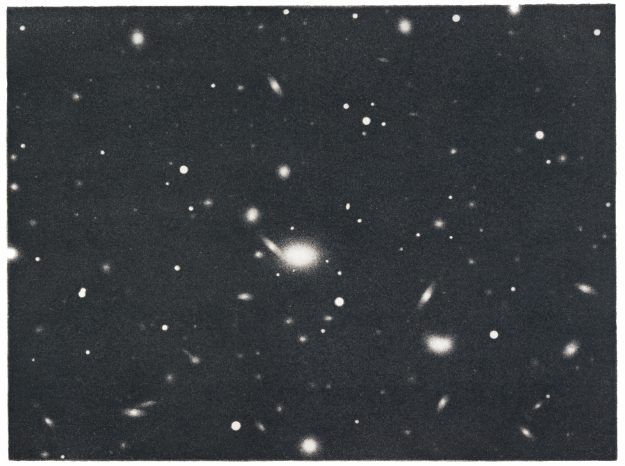

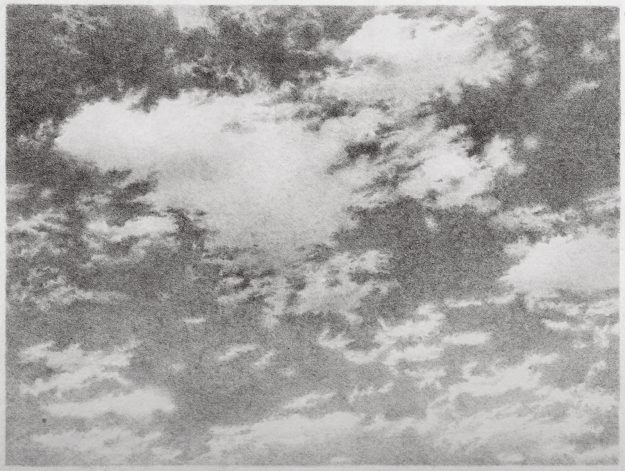

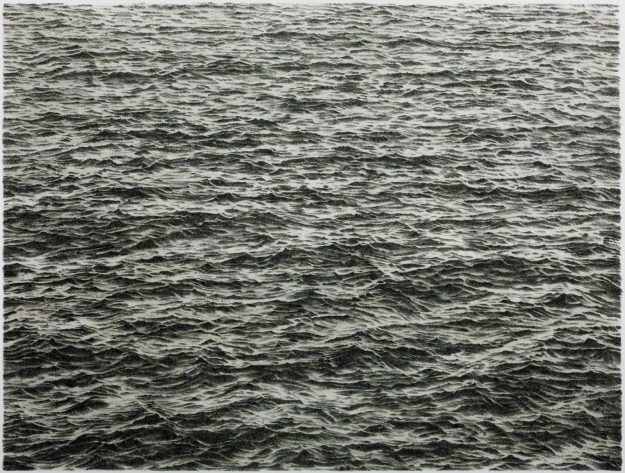

Still, the obvious question raised by this reasoning, given the massive disproportion between the sutra’s portrait of a boundless universe and our little lives stuck in first gear, is how we could ever tell whether this might be true. If we can’t detect in some concrete way the grand motion of the cosmos across time and space, then the sutra is effectively as useless as we feel on our darkest days. Indeed, for many decades this was the view of the Japanese Zen master Hakuin, who more or less dismissed the Lotus as a pack of lies. But then, one evening as he sat on the meditation mat, the chirping of a cricket shifted his point of view and he had his Great Awakening. Now Hakuin understood that we rarely notice our connectedness because it’s absolutely everywhere, like the water invisible to fish since they never leave it. Yet we feel the connection at those moments when the universe, as it changes course, makes us bend to the pressure of its weight. We could describe this pressure as “helplessness,” and we often do. But we could also call it “an embrace,” the world encircling us in its arms and whispering, “Relax, you’re home.” Helplessness is just connection misunderstood. We only feel disconnected when we focus on the one embraced so narrowly that we forget the embracer.

On the other hand, there’s something very, very wrong with telling a person who just lost her job, has gotten deathly ill, or now sleeps in her car, “The universe is sending you big love.” The aspect of connectedness we shouldn’t overlook is that if we’re all really one, we can’t treat others people’s suffering solely as their responsibility. While the Lotus consoles us with assurances about our future buddhahood, it also puts us on the hook for the sad condition of the world today and everybody in it. That’s why the bodhisattva Guanyin, “Universal Regarder of the Cries of the World,” arrives at a culminating moment in the text. And when she does, the sutra tell us this:

If someone faced with immediate attack calls the name of [the Universal Regarder], the swords and the clubs of the attackers will instantly break into pieces and they will be freed from the danger. . . .

If any living beings are afflicted with a great deal of lust, let them keep in mind and revere [the Regarder] and they will be freed from their desire. If they have a great deal of anger and rage, [it will be the same]. . . .Even if a woman wants to have a son and she worships and makes offerings to [the Regarder], she will bear a son blessed with merit, virtue, and wisdom. If she wants a daughter, she will bear [a female child] . . . who had long before planted roots of virtue and will come to be cherished and respected by all.

—trans. Reeves

Taken at face value, these claims aren’t true—unless you accept the possibility that the Regarder is who you are, as part of the “unlimited body” of all things. And in that case, you’re the only one who can make good on the bodhisattva’s words by offering the necessary help. Your efforts may fail, they may get rebuffed, or they could have unintended results, but by acting, all of us participate in the entire world’s enlightenment. Still, when we help others we don’t overcome our own fundamental helplessness. Instead, we see in the light of day that the giver is the one who most needs help, while those who accept what we offer them allow the Regarder in ourselves to emerge. Only the receiver can liberate us from our isolation.

Once we feel a rush of sympathy in response to others’ suffering and then take action to set things right, we may congratulate ourselves without understanding the deeper truth. Noble thoughts and emotions that we perceive as the best evidence of our initiative actually arise from a hidden place entirely beyond our control. We no more choose to act compassionately than we can consciously decide how we’ll feel 15 hours from now. I simply feel, I simply see, and compassion simply arrives, a gift from my buddhanature. I act, but I don’t initiate; I’m part of the effect but not the cause. True, when we meet the Regarder in ourselves, it can feel at first as though we’ve left behind for good the unfulfilled and needy Shariputra:

Listen to the actions of the Cry Regarder

How well [she] responds in every region [of the world],

[Her] great vow is deep as the sea

Unfathomable even within eons.

Serving many hundreds of billions of buddhas.

But only the Shariputra in ourselves will allow the Regarder to appear. Knowing that he won’t achieve buddhahood for a million lifetimes more, Shariputra has the patience to embrace every opportunity, large or small, as his bodhisattva work. And that means returning once again to the old self-doubts and uncertainties, now understood as aspects of the path.

Even though your head may start to spin when you try to think this matter through, the experience of disconnection, too, manifests our connectedness. One of my Zen teacher’s many teachers, the Kyoto School philosopher Shin’ichi Hisamatsu (1889–1980), used to illustrate this principle with a koan that I believe he composed in the years following World War II, as his country tried to extricate itself from a totalitarian disaster: “When you can do nothing, what will you do?” It’s a koan, though, that we’ll never quite resolve, because both parts of the statement express a reality that neither one can cancel out.

We’re always limited in countless ways by what Buddhist teaching represents as “causes and conditions” in the “three worlds of time.” Given these limitations, we’ll understandably dream of leaving our little lives behind by merging with that “unlimited body.” Then, as we might imagine, we can mobilize the power of the universe on our own behalf—the Buddhist equivalent, I suppose, of speaking for God. The Japanese viewed themselves in just this light when they invaded China, and so have Americans whenever they’ve believed in their Manifest Destiny. But such transformations from “man” into “God” are actually impossible, because the two have never been separate: we can’t become what we already are. Our helplessness is simply the universe itself when it’s acting small.

Pursuing liberation in our next life is also a way of being fully present now.

And so, tomorrow morning, at the sound of the alarm, we’ll jump into the shower and race for the train, coats flapping in the wind and socks slipping down. If the Zen master Pang Yun could see, he’d affirm that we’re radiating “supernatural power” when we “chop wood and carry water” in this modern urban way. But that makes it all sound too easy. Not the oneness, but the friction produced by great and small colliding—that’s what gradually enables us to purify “body, mind, and word,” cleaning up our karma in the process and becoming clearer.

As we do so, the Buddha promises, the Pure Land will reveal itself:

When the living witness the end of an eon,

When everything is consumed in a great fire,

This land of mine remains safe and tranquil,

Always filled with human and heavenly beings.Its gardens and groves, halls and pavilions,

Are adorned with all kinds of gems.

Jeweled trees are full of flowers and fruit,

And living beings freely enjoy themselves.

As far as I’m concerned, these two stanzas say it all: the universe consumed by the kalpa fire and the Pure Land exist at the same time. I’ll admit that this claim seems to contradict the more familiar notion of the Pure Land as the realm of the Buddha of Infinite Light, Amitabha or Amida. According to the familiar view, we can go to Amitabha’s paradise only after we’ve left this life behind, and only then can we attain the enlightenment withheld from us by our circumstances here. But Zhiyi insists that both accounts are true: pursuing liberation in our next life is also a way of being fully present now.

I agree because I’ve come to think that the Pure Land—as symbol and experience—isn’t quite the same as our timeless, formless Buddha-mind. Nor is it our ordinary consciousness in the realm of change, where the burning never stops. Instead, the Pure Land lies at the interface between the crazy roller coaster of events and the stillness we sometimes reach. Our helplessness becomes transcendental, then, at those moments when nirvana appears right in the midst of samsara. Suddenly we find ourselves in the perfect Land where “living beings . . . enjoy themselves.” And even when we don’t, we’re almost there.