Obon season is here again and unfortunately, due to the ongoing pandemic, we will not be able to hold our Bon Dance for another year. We all look forward to this annual ritual of remembrance for its fellowship, food, and fun. By gathering and dancing together, we make thinner the veil of separation between us and our departed loved ones, and we feel closer to them. Obon is truly a festival of joyful memory in which we celebrate life and our continuing relationship with those that have come before.

Not being able to celebrate Obon in the traditional way has made us realize how important rituals are in our lives. They can offer us connection, grounding, and healing. What makes rituals so special and powerful is that they are intentional. We consciously and mindfully undertake them so we can be reminded of what is truly meaningful in our lives.

In the Shin tradition, we believe that when someone dies, they become one with the Buddha. Therefore, while their physical form may pass from this world, the true essence of our loved one continues to live on in enlightenment, and the activity of enlightenment is always present in our lives. Our loved ones are always with us, embracing us, through the working of “Namo Amida Butsu,” [the recitation of the Buddha’s name, and Shin Buddhism’s central practice].

Obon reminds us of the great web of life—that our lives are made possible by countless causes and conditions that we should be grateful for. We are also reminded that we have a responsibility to create a meaningful life for future generations. While Obon is a festival of joyful memory, it is also a reminder that we are links between the past and the future. Obon teaches us how well we live in this present moment is the best way of honoring our departed loved ones.

Obon is truly a joyful gathering in which both the living and the dead rejoice in the universal embrace of the Buddha’s compassion. While our dancing is a physical act of remembrance for our loved ones, we also dance for ourselves. When we awaken to the timeless working of the Buddha’s vow in our lives, we can do nothing else but express our profound joy and gratitude. This is why we dance—because we realize our loved ones have become one with timeless reality that is never far from us.

But dancing during Obon is just one form of ritual that can connect us with our ancestors.

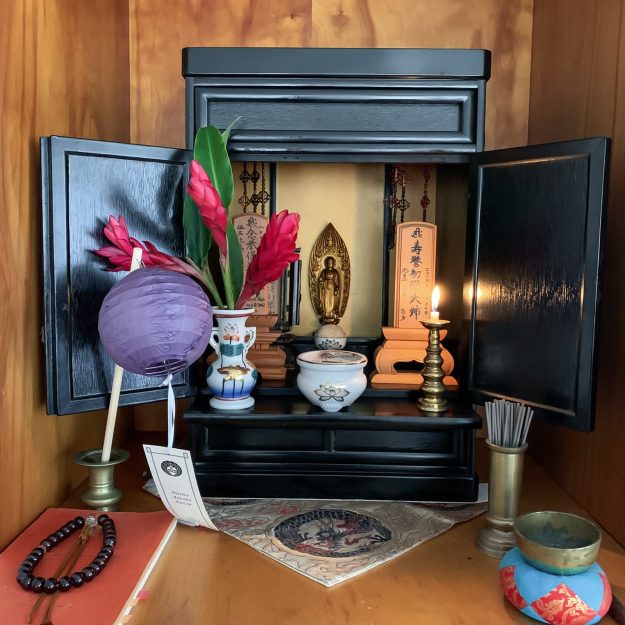

When I moved to Kona [Hongwanji Buddhist Temple] several years ago, my dad drove over from Hilo to deliver my grandparent’s obutsudan, [a family altar], to me. I don’t know how old the altar is but I remember them always having it. What makes the altar so special is that it contains my grandparent’s Ihai or wooden Memorial Tablets. My grandparents were such a big part of my life, that to be able to care for their obutsudan is quite meaningful. Each morning, I start the day by lighting a candle, offering incense, and chanting a sutra. This daily ritual of self-reflection reminds me of how I am always connected to the working of limitless Light and Life. I am also able to greet my grandparents each morning to thank them for their continuing influence in my life. While I live alone, I am not alone because they are always with me in the dynamic activity of Namo Amida Butsu. They have become personal Buddhas who help me feel ever connected to the rhythms and cycles of life. This ritual of starting my day with them and the Buddha has been healing especially during this time of pandemic.

What personal rituals do you have that connect you to your loved ones?

I know many people ohaka mairi, [the traditional custom of visiting the graves of ancestors, typically done during Obon], by cleaning and bringing flowers to family graves. Our temple columbarium and cemetery are always well kept and full of beautiful flowers. Besides flowers, people sometimes leave their favorite snacks and the occasional can of beer on special occasions.

These rituals have continued relatively uninterrupted during this pandemic. They remind us of our need for connection and how healing it is to be in relationship with our departed loved ones.

In the Amida Sutra, one of the three sacred scriptures of Shin Buddhism, we find the phrase kue issho. These beautiful words describe how we will all meet together in one place. It refers to how when we entrust in Amida’s vow and aspire for birth in the Pure Land, we will all meet together in the world of enlightenment.

In our tradition, it is customary to inscribe kue issho on headstones as a reminder of this sacred promise fulfilled by Amida Buddha’s great compassion. You might also find Namo Amida Butsu inscribed on many headstones. This is also customary because we continually meet our loved ones and experience kue issho in the dynamic activity of saying the Buddha’s honored name, or reciting the nembutsu. We meet our loved ones in the working of great wisdom and compassion that sustains our lives.

Not all rituals are necessarily religious, however. Do you make your mom’s favorite recipe for special family gatherings? Do you go to your grandfather’s favorite fishing spot? Do you pau hana, [a Hawaiian phrase for hanging out after work], with family and friends like your dad used to? Or do you simply tell your departed spouse good morning every day when you wake up? Think about the rituals you regularly perform that connect you to love.

These rituals of remembrance are truly about the life we continue to share with those who have gone before. They are life-giving and connect us to what is truly meaningful and real.

So while we cannot dance together again this year, we can all reflect on the ways our departed loved ones continue to enrich and influence our lives. This is the true spirit of Obon that we can always celebrate.

Namo Amida Butsu.

⧫

This post originally appeared here on Rev. Blayne Higa’s blog. Read more about Rev. Higa here in Tricycle magazine.