Having never asked for a birthday gift in my life, I found it difficult to do, especially when I was asking it of a man who has never cared for the aura around birthdays.

“I’d like to turn forty under that tree,” I said.

Like most women, I’d have liked to believe that a husband of long years would be able to interpret the italicized word in my voice. Like most men, my husband looked askance at me, trying hard to recover any clues he might have missed from a previous conversation.

We were talking in our bedroom, the room in which I spend most of my time when I am at home. It is an unusually large room. In one corner, by the giant windows that I open to let in the cool northern air, stands a big tree. I use the word “big” consciously—it is tall, much taller than my husband who is six feet tall. But it was dead. I had found it abandoned by the roadside near a church and had felt an onrush of affection and attraction for it immediately, of the kind that it is possible to feel only for dead plant life, not dead animals, or dead men. Soon after, the tree had become an occupant in our bedroom, the carpenter having given it wooden stilts so that death had not been able to take away what it immediately does—the dignity of the vertical position. Beneath that leafless tree now sat a statue of the Buddha, his eyes closed.

My husband turned to the tree and then to me. He looked confused. If his wife wanted to meet her fortieth year by sitting under that tree, who was he to refuse? Especially as, given the kind of person he is, he wouldn’t have been able to remember how his wife had brought in her thirtieth or the thirty-ninth—sitting on a chair or crouched under a table.

“Sure,” he replied after some thought. He sounded quite happy. I wanted to sit under that tree; I had not asked that of him. Not yet that is.

“Will you take me to meet the Bodhi tree then?” I asked. I was aware of the circuit that would break inside the travel-shy man. It was one thing to buy a young plant from the nursery and make an acquaintance with the stranger, quite another to travel more than 600 kilometers to meet an old tree. I heard, out his silence, a mixture of amusement and annoyance.

“Sure,” he said again, in the tone of one convincing himself.

“Why not a forest?” he asked later at night.

“That’s like comparing apples to oranges,” I replied, annoyed. Couldn’t he see the difference between a solitary tree and a forest?

But after he’d fallen asleep, I wondered why I’d been so annoyed. When the answer came to me I had to resist the urge to shake him out of his sleep. When he turned restlessly in his sleep I said to him, “One goes to a forest to get lost. One goes to the Bodhi tree to find oneself.”

Half asleep, he replied: “In both something is missing.”

I remember not sleeping that night and feeling terribly alone, the kind of loneliness that is stoked by the night. I remember thinking that all the world loves an infant. But as we age, the number of lovers we have dwindles. Our journey towards death, punctuated by birthdays, is a preparation for solitude. It suddenly struck me that my husband’s query, about choosing a solitary tree over a forest, could compare with that journey, our lovers reduced to no one but the self. Looked at another way, this was my humble, homemade interpretation of Buddhism, in which the focus is only on the self, for the world is beyond our control. And so a tree, not a forest.

In all this contemplation of sitting or standing under trees, a few things come to mind. I grew up in a locality that was bordered by Aamtala and Pakurtala on either side, the first a neighborhood whose name literally meant “under a mango tree,” the second a crossroad that meant roughly the same, except that instead of the mango, it was the pakur, the portia tree. “Tala,” meaning under, was a common suffix to the names of trees, and these had been used for naming hamlets, neighborhoods, even towns, and villages. In them is the whiff of an older history, of a world in which trees and their ecology of shade were important.

“Nothing happens” under a tree, and yet something does, something must, something so subtle that our eyes fail to register the changes. In a poem titled “Gachhtawla,” or “Under a Tree,” the Bengali poet Sunil Ganguly recounts the history of religion and the history of hate, of Rama and Rabindranath, of churches and gurdwaras, and the skies over Bangladesh’s Chittagong and Bengal’s Bankura, their indifference to borders of nations, and their fairy-tale borders. He calls out to Kanai and Kamal, two young men from the Hindu and Muslim communities, and asks them to join him in watching the procession of human history driven by the madness of “old fools.” “And we laugh at them from under a tree,” he says. And suddenly the polarity of two worlds floats to the surface with that line—the foolish violence of action-filled human history counterpoised against the “nothing happens” world beneath the tree.

Poets have always seemed to find something under a tree. D. H. Lawrence finds a similar counterpoint to modern history’s frenetic march:

Under the almond tree, the happy lands

Provence, Japan, and Italy repose,

And passing feet are chatter and clapping of those

Who play around us, country girls clapping their hands.

The poem is titled “Letter from Town: The Almond Tree,” and in it we find busy civilizations resting under a tree—”Provence, Japan, and Italy repose,” after the labor of these countries in the studio and the battlefield. Lawrence is unambiguous about the harvest of such an experience—under a tree are “the happy lands.” Around it is movement, of feet and hands, of young and the old, but under it is rest, the rest of temporary and happy forgetfulness.

It is this that Shakespeare memorialized in the play As You Like It—my childhood memories are annotated by these lines in my father’s baritone, he who had been raised in the shade of trees in his tiny village on the Indo-Bangladesh border:

Under the greenwood tree

Who loves to lie with me,

And turn his merry note

Unto the sweet bird’s throat,

Come hither, come hither, come hither:

Here shall he see

No enemy

But winter and rough weather.

Who doth ambition shun

And loves to live i’ the sun,

Seeking the food he eats,

And pleased with what he gets,

Come hither, come hither, come hither:

Here shall he see

No enemy

But winter and rough weather.

This immediate abandonment of worldly ambition would be familiar to anyone who has stood under a tree. Being under a tree is a holiday from reason—who has seen a bureaucrat clearing files under a tree after all? Imagine the Buddha with a briefcase, sitting under a tree. The shunning of ambition, time without structure, a carriage without rivals or enemies, not to mention the barter economy of oxygen and carbon dioxide that keeps animals alive—all these are gifts from life under a tree.

♦

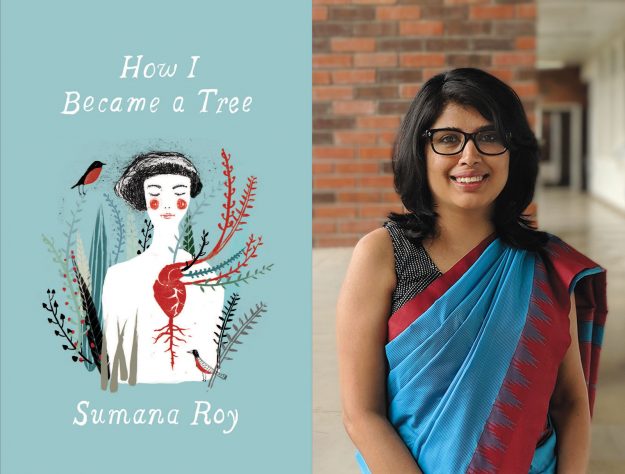

Excerpted from How I Became a Tree by Sumana Roy © 2021. Published with permission from Yale University Press.