As the days grow shorter and cold breezes begin to blow, our minds turn to ghosts and all things spooky. The exhibition Ghost Stories Are All Love Stories at The Clemente center in New York’s Lower East Side (on display through November 5) leans into the otherworldly. The ghosts here aren’t the type you’ll find trick-or-treating on Halloween wearing costumes made from white sheets, nor are they strictly the Buddhist hungry ghosts (Skt., preta), miserable beings suffering from insatiable hunger and thirst as a karmic result of their unchecked greed in previous lives. Ghost Stories Are All Love Stories is concerned with connection to intangible spirits and memories—connections that stretch across generations, geography, and time. The show defines its view of the ghostly as “a lingering affect that transcends linear notions of time and space, [and] finds parallel in love.”

Curated by writer, curator, designer, and translator Banyi Huang, the exhibit features four Asian American artists searching for “alternative modes of belonging and cyclical motions of time” in the Asian diaspora in the US, according to the gallery’s description. This intimate show—containing only 17 pieces—invites us to linger and take in the videos, drawings, and hand-crafted objects. Central to the show’s themes, but not explicitly invoked in the works, is the Ullambana festival (Ghost festival), a celebration of the cyclical return of ancestor spirits that is celebrated across Mahayana Buddhist cultures in East Asia—taking form as Obon in Japan and the Guijie or the Hungry Ghost Festival in China. It’s believed that during the holiday, the ancestor spirits leave their resting places to return home. People celebrate by returning to their hometowns to be with family, making ceremonial offerings to the spirits, and floating paper lanterns on bodies of water to guide spirits back home.

New York-based artist Lu Zhang’s video installation “How To Boil Time” captured my attention first. Zhang narrates a strange sequence of events as images loosely related to her words flash on the screen. Images include an intriguing juxtaposition of animal and plant photos, pictures of iconic Chinese scenes (pagodas, Tiananmen Square, the Great Wall), stills taken from news broadcasts, and photographs taken by the artist’s grandfather. The video follows the disjointed logic of dreams, where animals can transform and vivid scenes flow from one to another without explanation. On her website, Zhang states about this piece, “The state of swinging between the two cultures / Feels like half-dream and half-awake.” She has installed a spinning lamp sculpture titled “Elysium Fields” in front of the video; the colorful patches of light add to the dreamlike atmosphere. In another installation, “But Lost Also A Lie,” images from the video “How To Boil Time” hang from a ceramic laundry hanger, the kind typically used to dry underwear and socks. I walked away with impressions of the relationship between the linear, mundane everyday and the more subconscious world of dreams and relationships.

Further into the gallery, Banyi Huang’s sculpture “Summoning Wind and Calling Rain” consists of two green, ghostly figures, one atop the other, with white mask-like faces and black eyes and mouths (resembling the ghost No-Face in Studio Ghibli’s iconic anime film Spirited Away, about a young girl trapped in the realm of Shinto kami, or spirits). One brandishes chains while the other holds a paintbrush and regurgitates a steady stream of black ink.

Another video installation, “DONG 洞,” a collaboration between Banyi Huang and Maya Yu Zhang, is described as a “porno-horrific-fantasy set in a lunar cave.” A dancer awakens in a cave, dons a mask, dances, and interacts with two sculptures in the show: “Apparitions,” a lamp made of three Buddha heads wearing clown-like makeup, and “It’s Cold in the Lunar Palace But Warm in Your Embrace,” a white ceramic piece. This video embraces eroticism and fuses it with religious and mythical imagery.

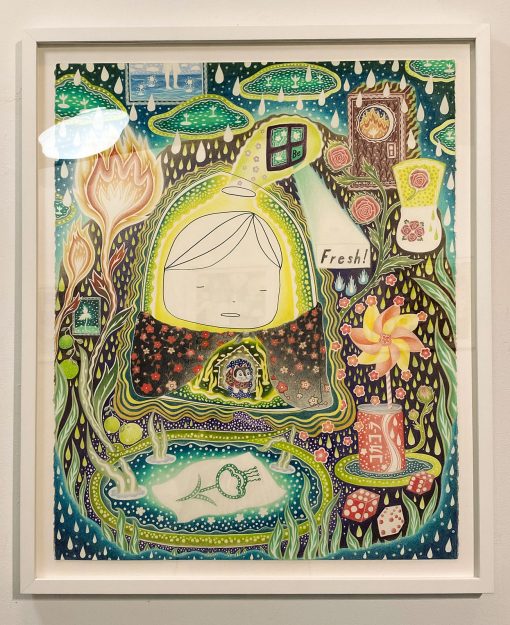

Mei Kazama has contributed eight striking colored pencil and pen drawings. Their work calls for you to bring your nose close to the glass to trace how their collage-like drawings blend portals, windows, and domestic space to create a sense of childhood memories seen through a lens of the dreamlike and supernatural. There are repeated motifs of a windcatcher, flowers, raindrops (or petals?), and flying figures. It’s as if we’re getting a peek into a personal interior space, one person’s story viewed through a kaleidoscope of time.

“Who Left the Light On for Me,” the last piece in the show, is an oil painting of Lu Zhang’s grandparents’ living room after their death; the cozy domestic space is illuminated with a warm glow. Did the ghosts of the painter’s grandparents leave the light on for her? I don’t know, but I like to think so, in an intergenerational ghost story of love.

♦

If the show stimulates your creativity, you can share your experiences with the otherworldly with the curators; they invite visitors to share reflections in art, audio, short stories, or any other format. Their prompts include “Who are the ghosts you know and love?”, “What is ghostly to you?”, and “How do you cultivate love in the ghostly realm?” Email your response to ghoststoriesarealllovestories@gmail.com, leave a voice message at (917) 633-6401, or leave materials on the table in the gallery. They will compile responses into an archive after the show closes.