SUNDAY, July 25, 1993. Smiling, bespectacled George Weissman meets me at Tel Aviv airport at four-thirty A.M. We drive north up Highway Four via Haifa to Nahariya. George is a nuclear physicist from Berkeley. We discuss Sautrantika and Yogacara philosophy as we pass through dusty towns and villages in a muddle of construction. At Nahariya we turn inland. After straying for miles through country roads, Druze olive farms, and a kibbutz, we locate Clil, an ecological village of thirty families in the hills of western Galilee.

“Buddhism and Consciousness” is the title of the retreat at which I am to give a series of lectures. It has been arranged by Stephen Fulder, a writer on herbal medicine with a long-standing interest in Buddhism. I am to stay at his self-made, solar-powered house with Stephen, his wife, Rachel, and their three charming daughters.

Over a lunch of olives, hummus, tahini, salad, and bread, I hear several staccato bursts of gunfire. I imagine soldiers are doing target practice nearby. “Katyushas,” explains Aurielle, the youngest daughter. “Rockets from Lebanon,” she adds to dispel myevident confusion. “Will you pass the hummus, please.” Every few minutes a dull thud interrupts the meal. Fear tightens my belly. “During the Iraq War,” recalls Aurielle with unassuming pride, “at night we used to watch the SCUDs on their way to Tel Aviv.” As fresh grapes from the vines around the house are served, the massive thump of a rocket or shell is followed by a palpable reverberation.

Stephen Fulder is only slightly concerned that the train to Nahariya bringing the course participants might be held up because of the fighting. He has heard on the radio that the town is under rocket attack, stores have closed, and people are in shelters.

By mid-afternoon almost everyone has arrived. They sit under trees in the garden chatting, laughing, and sipping cold lemongrass tea. When the intense dry heat of the day fades, we sit in a circle and introduce ourselves. Many are professionals: teachers, psychologists, therapists. One man is here because his daughter has been in India for two years, living in poverty and meditating. He blames Buddhism for this.

MONDAY

I pass on the morning session by Dr. Lydia Aran because it is in Hebrew. Lydia is the author of the only book on Buddhism in the language. It has sold well and received wide coverage in the media. She tells me that Buddhism is drawing widespread attention these days in Israel, partly because of a growing interest in other forms of spiritual practice, partly because young Israelis are now able to get visas to travel and study in India. Nonetheless, there is as yet no Buddhist center in the country. Some years ago a Japanese Roshi lived in Jerusalem and ran a small group, but he left to become abbot of Ryutakuji, a monastery near Kyoto. Informal vipassana meditation groups are all that exist here.

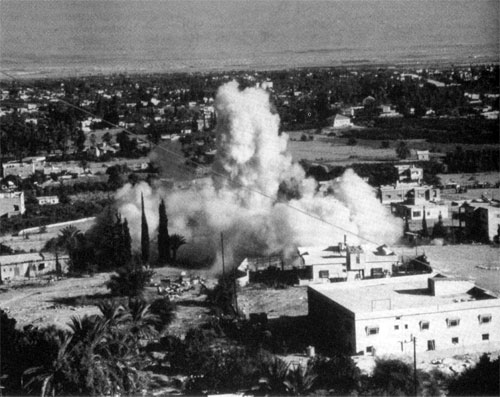

Throughout the morning I hear a continuous series of dull, distant thuds. I learn that these are Israeli artillery bombardments of Hezbollah positions in Lebanon. Clil is only fifteen kilometers from the border.

As I walk through this stony, thorn-strewn land where olive, fig, and pomegranate trees somehow flourish, I am almost envious of this religion that is grounded in such a physical sense of place: Israel. Unlike Buddhism, Judaism is rooted in home rather than homelessness. The land itself evokes the biblical sources of Western culture. Although she has studied the dharma for years in Nepal and is not an Orthodox Jew, Lydia says that she cannot become a Buddhist because she would be betraying those who died in the Holocaust. “You can be a German Buddhist, an English Buddhist, but not a Jewish Buddhist,” she declares. She is surprised that when she told her Tibetan lama this he did not understand. I tell her I am not sure I understand myself.

In my opening talk I describe how ignorance (avidya) and conditioning activity (samskara) are the context within which consciousness as we know it emerges. Shantideva compares the human condition to a dark, cloudy night occasionally and briefly illuminated by a flash of lightning. The lightning is awakening consciousness (bodhichitta), which pierces the darkness with wisdom and compassion.

At dusk, Rachel Fulder, in a somewhat distraught state, explains that she has to go to the funeral of the son (by a former marriage) of her sister’s husband. Two weeks ago the tank in which he was patrolling the security zone was hit in a Hezbollah ambush. Severely brain-damaged, the young soldier lay in a coma until he died yesterday. His death is given as one of the official reasons behind this latest round of Israeli retaliation.

All evening mustard-colored helicopters whir and clatter overhead on their way north.

TUESDAY

Consciousness, I continue, is always referential. Buddhism acknowledges no “pure consciousness.” We are always conscious of something. There is no retreat from the encounter with the world to a spiritual realm of pure awareness. Nor is consciousness an independent “thing.” Just as the hand is made of bones, flesh, skin, and nerves, so a moment of consciousness is constituted of stimuli, feelings, intentions, attentions, and perceptions.

It is hot, and the room is buzzing with flies and mosquitoes. People do not seem concentrated. The dry wind comes in gusts, muffling the shellfire, making it sound like distant thunder. Silver jets fly in silent formation northward. Stephen tells me at lunch that two hundred thousand people have fled their homes in South Lebanon to escape the bombardment.

In the afternoon, Marsha, one of the participants, comes to talk to me. She is frustrated that no Israelis are willing to support her in rehabilitating torture victims. The Palestinian groups in Nablus with whom she works estimate that forty-five thousand Palestinians have been tortured. She has just returned from a yearlong, worldwide spiritual quest in search of an answer. Now she is angry that “spiritual” people who talk endlessly of compassion are as uninterested in her work as everyone else. “This society is mentally sick,” she says.

The Fulders are fasting to commemorate the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem nearly two thousand years ago. So George and I have dinner with Danny, a Jewish vip ass ana meditator from L.A., who is also the sheriff of Clil. “Hi!” he greets us warmly from his patio, “you’ve arrived just in time for our latest war.” But behind the bonhomie he is worried that this conflict may drag on. His long-haired teenage son sees no future in the country. Danny disagrees. “Israel bubbles with reality,” he says. That’s why he stays.

WEDNESDAY

Over breakfast on the lawn, Yasmin, the elder daughter, tells of how she was nearly hit by a Katyusha in Nahariya the previous night. She was staying in a friend’s house. The rocket landed at the end of the street. “It was so loud it made the sky shake,” she says. She is going back to the town today for the free ice-skating being offered to the residents as compensation for the shelling.

“We poor Katyusha-hit northerners,” mutters Rachel, ironically. “Portrayed as heroes of the nation by the press.” A holiday for her, she explains, is simply to live normally at home. A holiday from fighting, from funerals, from people throwing themselves onto newly filled graves, from distraught parents. When there is war on, everyone has someone close to them involved.

I can stand this unreality no longer. Before beginning my lecture I stammer out my feelings about the war. About how each thump means the destruction of a village, the obliteration by shrapnel of people who brush their teeth each morning, who eat grapes and sip tea, who play with their children. Each dull thud is physically sickening. How can we politely discuss theories of consciousness with this carnage going on around us?

People respond with quiet conviction and passion. Apart from Marsha, they do not wish to discuss the situation for fear of it degrading into a political dispute. We spend most of our lives endlessly talking about these problems, they say. We have come to this retreat to find some moments of sanity, to learn some skills that might help us cope more effectively. We don’t want to talk about it not because it’s unimportant but because it’s too important, says Benni Sharon, the cognitive scientist. A former army colonel recalls how angry he used to get when returning home from duty in the Sinai to find people having fun. He slowly realized that people’s ordinary lives must continue and be celebrated in all their trivial detail. In this country, war is a way of life.

These declarations have allowed us to acknowledge a deeper purpose to the course. They have united us. I speak of the empowering factors of consciousness: faith, enthusiasm, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. The ubiquitous term “practice” means to strengthen these qualities in equal measure. In the discussion that follows people talk openly and sincerely about their experiences and difficulties in meditation.

In the evening, at Stephen’s request, I lead a Tibetan guided meditation on compassion and love (tonglen). As we breathe in we inhale the suffering of the world in the form of smoke. It dissolves the ego-centeredness visualized at the heart as a black egg. As we breathe out we exhale, in the form of white light, the wish for all beings to be well. Gradually we extend the scope of our awareness from our families to the soldiers on the front, to the Hezbollah guerrillas. Outside we hear the rattle of helicopters and the concerted howling of jackals.

Afterward some say the meditation made them feel powerless and frustrated; others recognize that feeling compassion alone is inadequate; some argue that we should concentrate not on people’s suffering but on their joy. I feel like an intruder into something I do not understand. This is confirmed by a tall, agitated man who speaks to me after the others are gone. He resented being subjected to “an artificial process that made an abstraction out of what was an immediate and personal concern.” This sort of exercise “might be appropriate for those removed from this kind of situation, but not for those within it.” I tell him how confused I am. How a few days ago I was in the tranquil English countryside and suddenly I find myself in a war zone. “This is not a war zone!” he declares with bemused indignation. “We are at least two kilometers outside the range of rocket fire.”

THURSDAY

The Buddha described the dharma as “going against the stream.” As long as one swims with the current of a river, one remains unaware of it. But if one chooses to turn against it, suddenly it is revealed as a powerful, discomforting force. The “stream” refers to the accumulated habits of conditioning. The practice of dharma means to turn around midstream, to observe mindfully and intelligently the forces of conditioning instead of impulsively reacting to their promptings.

A woman from Jerusalem describes how, during the meditation sessions, each time she hears a shell explode in the distance her reaction is to run to a telephone, to set in train a series of impulsive inquiries rather than simply remain with the sound and the complex of painful feelings around it.

The cycle of conditioning is interrupted above all through being mindful of feelings. Especially when the feeling is one of pain, it requires singular strength of mind to accept and recognize that pain. For our tendency is to push it away by reaching for a well-lubricated strategy of reaction. To stop and remain still means neither to suppress nor to express one’s aversion to pain. It means to notice one’s psychological behavior at its inception rather than when it has overwhelmed one and it is too late. It means to create within oneself the ground of equanimity, from whence to choose freely a more sane course of action.

Around four o’clock Stephen announces with joy and relief that the Americans have interceded and that a cease fire will come into effect at six P.M. As we walk home through the parched fields, we notice that the thuds and rumbles have stopped.

“It doesn’t sound like a cease fire,” says Rachel over dinner by candle light in the garden. If anything, the shelling is resuming with greater intensity and at closer range. It goes on all night, the explosions urgent and insistent. Around midnight I am awoken by the roar of helicopter blades. Impelled by unimaginable fears, I rush outside to glimpse a sinister, low-flying machine thundering northward.

FRIDAY

If, as much of traditional Buddhism suggests, all human experience is rooted in ignorance, then how can one explain the emergence of the wish to be free from ignorance? This, more than anything else, confirms the idea that the underlying nature of consciousness is one of radiancy and knowing. No matter how tenacious and pervasive they may appear, ignorance, craving, and grasping are nonetheless adventitious afflictions—like mud that soils the purity of water or rock that conceals its seams of gold.

The concept of Buddha-nature gives hope that even in the darkest moments of consciousness, a lightning-flash of understanding and tenderness may break in. The practice of mindfulness and equanimity opens one to the possibility of such irruptions.

The course ends at lunchtime. After hurried, impassioned farewells the participants depart. The village of Clil is returned to its normal routines.

SATURDAY

I observe the Sabbath with the Fulders: sleeping late, not answering the telephone, mixing tahini for lunch. The shelling dies down toward midday, then stops.

Stephen tells me of his wife’s displeasure at the presence of a small Buddha image that had been placed on a table in the lecture room. She had asked that it be removed immediately. Any suggestion of worship of graven images is intolerable for her since it breaks the first law of Judaism.

As we walk in the hills just before dusk, Stephen recounts the story of Clil’s resistance to war. Some years ago the residents of the village decided to launch a peace movement that would begin with a well-publicized march. For months they threw themselves into the organization and fund-raising required to make the event a success. The march took place; it was even featured in The New York Times. When it was over, they asked themselves what they had achieved. Their resources were depleted. Their fields had been taken over by weeds. Their children had been neglected. They agreed to abandon the peace movement and concentrate instead on peacefulness in attending to the tasks of daily life.

Upon returning home to London the next morning I learned that Israel had declared a cease fire shortly before I left Clil on Saturday night. It was estimated that during the seven days of bombardment the Israeli army had delivered $60 million worth of shells, wire-guided missiles, and bombs. Around three hundred thousand people, mostly villagers from South Lebanon, had been made homeless.

One hopes that the recently signed peace accord between Israel and the PLO will finally bring to an end the long history of violence that has beset the Middle East. Hezbollah, however, have yet to show any sign of reversing their hostile stance toward Israel.