Our world is on edge. COVID-19 cases and deaths, out-of-control forest fires, racial and social injustice—all are exacerbating a growing mental health crisis as more people wrestle with negative emotions: fear, anxiety, loneliness, anger, resentment. What is the role of Buddhist wisdom and practice in achieving greater emotional well-being? Could transforming our emotional states build the resilience needed to cope with uncertainty, and create a better future?

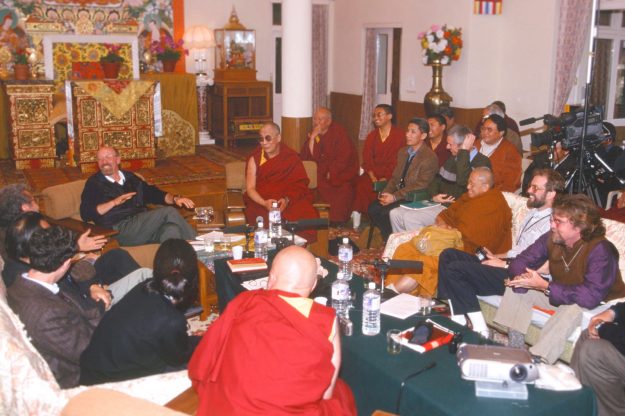

One search for answers in the West can be traced to a seminal event in the year 2000. It was then that His Holiness the Dalai Lama hosted twelve renowned scientists and philosophers at his home in Dharamsala, India for a Mind & Life Dialogue on destructive emotions. Over five days, researchers and practitioners explored how Buddhist contemplative practices could be studied scientifically and applied to help people achieve greater emotional balance.

The event catalyzed a new movement in the West to study emotion and the impact of Buddhist meditation and other contemplative practices as described in Daniel Goleman’s bestseller, Destructive Emotions. Over the last two decades, related research findings have contributed to transformative changes in large-scale systems from education to healthcare.

One of those present at the 2000 dialogue was Thupten Jinpa, the Dalai Lama’s long-time English translator and current Chair of the Mind & Life Institute. Below he shares how Buddhist contemplative wisdom has been applied—in secular ways—to address contemporary challenges and the opportunities that lie ahead.

Can you share the origins of the 2000 Mind & Life Dialogue on destructive emotions? What prompted the focus on emotion? The dialogue was part of an effort by His Holiness and western scientists to engage more deeply around the psychological sciences—specifically to examine whether bringing awareness to our experience of emotion could have a measurable impact.

His Holiness put forth a challenge to participants. Modern science had been amazingly successful in mapping pathologies of the human mind and mental disorders, but there was nothing comparable when it came to the positive qualities of the human mind. He asked: can’t you use the same rigor and techniques to study positive emotions?

He also wondered whether there were techniques from Buddhist contemplative practices that could be adapted and universalized—through a secular approach—to benefit humanity and ease suffering. These two challenges are why this meeting is seen by some as a springboard for what we call today contemplative science. The focus on emotion was a big part of that.

How does Buddhist theory view emotions? Buddhist psychology doesn’t distinguish between thought and emotion in a neat way. In fact, there is no word for emotion in the classical Indic languages. There is an understanding that even what seems like a neutral state of mind will have an emotive tone. In contrast, in the West, human life is often seen as a struggle between emotion and reason. This dichotomy has deep roots in western thinking, so the emergence of the idea of emotion as separate from thought isn’t that surprising.

While the western scientific classification of emotion is value-neutral, in the Buddhist tradition there’s a goal: to seek enlightenment. This poses the question of what factors need to be cultivated or eliminated. In Buddhist psychology, you have a classification of six root mental afflictions—attachment, anger, ignorance, pride, doubt, and wrong view—along with 20 derivative or secondary afflictions, like rage, envy, and deceit. And then there are virtuous mental factors like equanimity, self-respect, and diligence that kick in when we engage in a good deed. You can see that there is an ethical underpinning, which is the path to liberation.

What were some of the barriers to studying emotions using science? The systematic, rigorous scientific study of psychology and emotions in the West emerged fairly recently. This has to do with science needing to have clarity around the constructs, or concepts, to be studied. For example, emotion is a construct, attachment is a construct. On top of that, scientists need to find appropriate measures. Without clarity around constructs and how you measure them, scientific inquiry can’t really progress.

When neuroscience began to look at the functions of the brain, a large part of the focus was on cognitive aspects such as thought, language, and intention. Emotion was seen as too nebulous. I think that was probably why emotion did not attract a lot of research attention initially. Part of it may have also had to do with a bias in western intellectual thinking dating back to Plato’s time. Priority was given to the rational dimension of the human being. Emotion was viewed as something that clouds judgment and takes you away from being truly human.

The emergence of brain imaging technology like functional MRI (fMRI) in the early 2000s made it easier for scientists to look at brain function. On top of that, there was growing interest in the role that emotions play in human behavior. Emotion as a motivating force was recognized early on in Buddhist psychology, which held that even though emotions are very natural and powerful when they arise, we can bring awareness to the experience of emotion, which offers us the possibility to self-regulate. This was a novel idea in the West, where coping with strong emotions often involved a chemical approach to numb feelings.

Today, creating spaces and offering techniques to regulate our emotions is widely accepted; twenty years ago, that was not the case. The early Mind & Life Dialogues helped to propel these ideas forward and bring these to scientific study and understanding.

What are some of the ways contemplative practice can be used to cultivate positive emotions? We now have evidence that through mindfulness practice, we can learn to regulate emotions. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), for example, has been shown to help prevent the relapse of depression. One of the things that perpetuates depression is rumination. Rumination tends to focus on “me” and creates a self-reinforcing spiral. MBCT offers skills for people to watch their mind so that they don’t get pulled into a negative spiral. One could argue that as you regulate strong emotions on the negative side, it opens up space for experiencing more positive feelings.

But there are also contemplative practices such as lovingkindness, compassion, forgiveness, and gratitude that offer a more direct approach to nurturing positive emotions. A lot of work has been done, particularly by social psychologist Barbara Fredrickson, on the role of lovingkindness in promoting positive emotions.

Lovingkindness and compassion practices emphasize a feeling of connection with others that is conducive to positive emotions like joy and a sense of fulfillment. It’s no coincidence that in most religions you have group practice that creates a sense of community, allowing you to go beyond yourself. Many of the contemplative practices, particularly the lovingkindness and compassion-based approaches, tend to do that. The next big wave of scientific study of contemplative practice could arise from these more relational, connection-based contemplative techniques.

So building positive relationships has a lot to do with our experience of positive emotions? Human beings are social creatures. A large part of our experience of happiness and suffering results from our interaction with, and relationships with, others. Each of us has a deep yearning for connection. That’s one of the reasons why loneliness kills. And if that’s true, then the opposite of loneliness—our feeling of connection with others—has to be good for us. It’s not surprising that a Harvard longitudinal study of adult development that looked at life satisfaction among a group of men over a period of 80 years found social connection to be the leading predictor of happiness and longevity among those studied.

What is the role of negative emotions like fear and anger, and how can we constructively channel these? I think people would agree that many of the problems in our lives are caused by not being able to regulate our emotions. Based on Buddhist psychology we can recognize two types of emotional awareness. One is awareness at the arousal level when you’re being triggered—this is a very embodied sense. The second is emotional literacy, which has to do with recognizing why you’re feeling a certain way—this is more conceptual and narrative-based. So, at the foundation of regulation is really awareness.

When it comes to emotions like anger or outrage, awareness and regulation become all the more important to help us channel feelings in productive ways. One only need to look at Nelson Mandela or Mahatma Gandhi for examples of strong moral beings who channeled the energy of their moral outrage to stand up against unjust systems. The Buddhist Tibetan tradition suggests that a skillful person can apply the energy that strong emotions like anger bring in constructive ways.

Could you clarify the distinction between empathy and compassion? What have we learned over the last 20 years about how they are different and why is that important? Some of the pioneering work to differentiate between empathy and compassion was done by child development psychologist Nancy Eisenberg, who participated in one of the early Mind & Life Dialogues. She was interested in a simple question: why is it that some children go and help when their friends are suffering, while others can’t cope and get distressed? Her study looked at what differentiated these two types of children. This was in the early eighties, before modern brain imaging technology.

Later, with the advent of MRI and fMRI, social neuroscientist Tania Singer and her team tested Eisenberg’s ideas using neuroscientific tools. At the brain level, they asked if it was possible to differentiate the expressions of empathy and compassion. One could argue that this whole research approach was informed by Buddhist thought, where compassion is seen as having a motivational element. Based on conversations with Buddhist scholars, Singer and her team were interested in this motivational element around compassion, and indeed their findings suggested that when compassion kicks in there seems to be greater activation in brain systems involved in motivation, action, and reward. When participants just felt empathy for suffering (without compassion), their own pain systems were active as well.

A key distinction between compassion and empathy is that in empathy, the focus is on the problem or the need, and the response is primarily emotional. With compassion, the focus is not just on the problem, but also the solution. It’s a more empowered state. One could say that compassion offers the outlet for empathy and helps regulate empathy in a constructive way.

How are contemplative perspectives on emotion being integrated into education, healthcare, and other areas of society? Mindfulness-based emotion regulation techniques are now widespread within school curricula. Some school programs are starting to integrate more compassion and relation-based approaches that can be traced to the Buddhist tradition of lovingkindness and compassion practices. The Crown Institute at the University of Colorado, for example, is integrating a compassion component into K-12 teacher training. Following the success of mindfulness training in schools, compassion-based techniques are the next resource. This is something we’ll be seeing more of as kind of a mindfulness 2.0 in education.

In healthcare, there’s also a huge interest in compassion-based approaches for strengthening resilience, promoting wellness, and preventing burnout among healthcare professionals and caregivers. Many doctors and nurses are faced with acute suffering in their patients every day, and they often cope by suppressing their own emotions. That may work for a while, but it can contribute to emotional exhaustion, or the failure to connect with another person.

Increasingly, people are recognizing that bringing compassion into healthcare and other settings is the way to go. At the Compassion Institute, for example, we’ve developed a six-week protocol, “Caring from the Inside Out,” designed specifically for physicians. It’s delivered over a one-hour lunch break, once a week for six weeks, and explores skills to move from empathy to compassion. People are really beginning to open up. This is one area where compassion-based contemplative practices can play a powerful role. We’ve also been working with law enforcement, where, again, it’s important to bear in mind the humanity of others before jumping immediately from a fear-based response. We are currently experimenting with compassion-based programs designed for this population, too.

What do you see as the ultimate goal of using contemplative approaches to work with our emotions—particularly in shifting one’s focus from “me” to “we”? Simply put, one of the key resources for our own personal well-being is within us. It’s our mind, and the power we have to bring awareness to our experience. Another important piece is connecting with our compassion, which is part of who we are.

Compassion is relational. It’s about others. It offers a way to connect with fellow human beings who look different from us and find a way to think more collectively. Many of today’s problems require collective solutions. Contemplative insights and wisdom have the potential to change human consciousness for the better.

We need to find a way to translate compassion and other prosocial emotions into our everyday behavior—not just at the individual level, but at the societal level. My hope is that through the efforts of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the Mind & Life Institute, the Compassion Institute, and many others, we’ll bring this conversation forward and start embracing the better part of who we are, and using tools in our own mind, like awareness, to see the world in a different way.

This is already beginning to happen. Today’s social movements are opening people up and calling for awareness of the profoundly inequitable structures in society. When we broaden our awareness, we see things more clearly. And when we see challenges more clearly, we have a better chance of addressing them in a constructive way.