When June Millington and her sister, Jean, first began singing and performing music in their early teens, they never thought they would one day become part of one of the leading all-female rock bands of the very masculine 1970s music scene, let alone the the first all-female rock band to release an album with a major American record label.

“It was like being in our own club,” Millington, now 73, told Tricycle. “Nobody could possibly have understood. To say that we were going to play electric guitar and bass was like saying that we were going to the moon.”

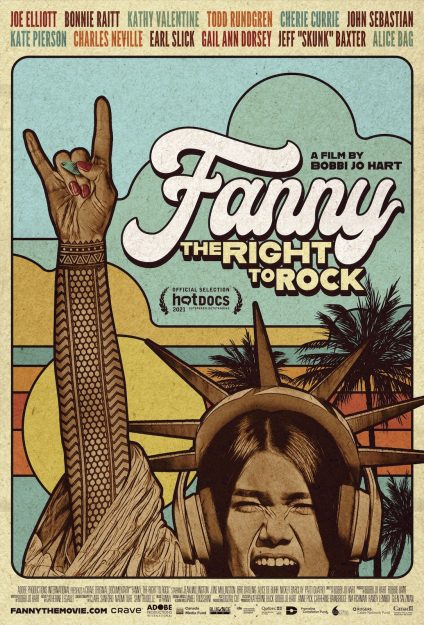

A new documentary, Fanny: The Right To Rock, directed by Bobbi Jo Hart, chronicles the band’s rise to fame and recent reunification 50 years after their first album. The film is currently being screened at film festivals across the country and features musicians including Bonnie Raitt, The Go-Go’s, The Runaways, and Todd Rundgren reflecting on the impact Fanny had on the American rock scene. In addition to tracing the band’s roots from the Philippines to their 1970s heyday, Fanny also explores how the Millington sisters and early drummer Brie Darling reunited in 2018 for their latest album Fanny Walked the Earth, which features Millington’s classic guitar riffs and songwriting. For longtime fans, the release of Fanny Walks the Earth and Hart’s documentary are long-overdue tributes that cement Fanny’s role in music history.

Born in the Philippines to a naval officer father and a Filipina mother, the Millington sisters spent their early childhood immersed in Filipino culture before moving to California in the early 1960s. While attending Catholic school in Manila, Millington heard the guitar for the first time, and her life changed forever. “Right before we moved from Manila to Sacramento I had actually heard a mysterious young girl playing guitar at the convent. I never saw her face, but I heard the sound down the hall and I walked over like I was sleepwalking,” she says. “She never turned around but I watched her for a few minutes before I went back to the classroom.” That was the moment she fell in love with the guitar and knew that music would be part of her life.

Just a few weeks later, Millington’s mother gifted her a pearl inlaid guitar for her thirteenth birthday. The siblings would hone their love of music and performance on the ship from Manila to San Francisco—a journey that spanned several weeks. “There’s a photo of us, me and Jean, playing two guitars for the officers on the ship,” she recalls. “They must have had us singing at lunchtime or dinner. That was our first audience.”

Along with keyboardist Nickey Barclay, drummer Alice de Buhr, and percussionist Brie Darling (a fellow Filipina American), the Millington sisters formed Fanny’s original lineup while the musicians were still in their teens. The group made history in 1970 when they released their self-titled debut album, becoming the first all-female band to release an album with a major American label. In spite of the sexist music press of the time, the band quickly became known for strong songwriting and for covers of rock classics like “Hey Bulldog” and “Badge.” A 1971 New York Times review of a live show noted in its headline that Fanny’s immediately apparent star power “pose[d] a challenge to the male ego.”

Coming of age within the dynamic California music scene and mingling with legends like David Bowie, John Lennon, and The Kinks, the band members found themselves in a whirlwind of celebrity friendships and—as the new documentary details—the sex, drugs, and rock and roll lifestyle of the early 1970s. Amazingly, though, even when she was performing at places like the famed West Hollywood club Whisky a Go Go, Millington says she was able to embrace stillness. “I would go in and out of being in my center where it’s really quiet. I’m doing my bit, but I’m reaching into the silence for my bit, whereas it’s all happening outside of me,” says Millington of her life as a performer. “I’d perceive the crash and the boom and the loudness of the music, and then I’d go back into the stillness.” This internal grounding amid all the chaos was a harbinger—or even an unconscious practice—of her future spiritual journey.

Even at the height of Fanny’s fame, Millington began wondering what else was out there. “I was a real seeker. I was looking for not just a place to land but a place where I could get knowledge,” she says. “I wanted to start to feel more safe in this world because I definitely felt very unsafe.” That feeling of unease began long before she had ever stepped on stage. Millington recalls being deeply affected by growing up in the ravaged landscape of post-war Philippines. “I had this feeling like ‘I just don’t understand it, but I feel like I’m in danger. I gotta figure something out.’ But that never reached my consciousness in the sense that I knew what I was looking for.”

While Fanny was cranking out albums—five in five years between 1970 and 1974—the singer turned to books and poems. “I am a bookworm, quite frankly, I just swallow books. So it was perfect for me to look in that direction.”

Millington began researching Tibetan Buddhism while browsing bookshops on tour. “The first book that really hit me like a sledgehammer was Chögyam Trungpa’s Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism,” she says. “It was so profound that I had to go over it again and again. Sometimes I would just read one paragraph, and then rest and meditate on what exactly he was talking about,” Millington continues. “Because I knew nothing, right? I didn’t grow up in that tradition.”

Although a broader interest in Buddhism and other Eastern traditions was taking off in the 1970s in the US, Millington says she often felt alone when it came to her spiritual interests. “I didn’t know anyone who was getting into Buddhism the way I did, even when it came to just reading about it,” she recalls. “I did hear that some of the Beach Boys were doing a mantra so I went to the Transcendental Meditation Center in Hollywood and got the mantra,” she adds. “I realize now that it was a general mantra, but it did get me started [with meditation.]”

“I don’t think people were embracing things. I think they were embracing the lingo,” Millington continues, “but I don’t think they were getting into it in the way that when you really open your heart, and you step on the path, you can make a lot of changes.”

Indeed, Millington’s spiritual journey often left those around her, including her bandmates, somewhat bewildered. One manager would even tease Millington about her “rabbit food” when she embraced vegetarianism. “The rest of the band kind of put up with me doing yoga every day and my breathing exercises and all that kind of stuff,” she recalls. “That was at a very basic level, but those practices definitely opened me up [to Buddhism].”

Soon enough, Buddhist themes of compassion and generosity began showing up in Millington’s songwriting, as in the 1972 song “Think of the Children,” which contains the lyrics:

Are you ready to think of the future?

To think about somebody else?

It may be your children’s children

And not just yourselfThere’s a kingdom below the ocean

And it stretches beyond the sun

There is more than we ever imagined

It’s for everyone

Eventually, she didn’t see much of a division between her songwriting process and her Buddhist practice. “They’re the same,” she says. “To me, music is sort of gliding within light. And Buddhism is, let’s say, floating within light.”

Millington ended up leaving Fanny in 1973 to explore new avenues, including her spiritual studies. “I needed to settle into a space where there wasn’t a whole lot of movement, so I could do my Buddhist meditations and go into the teachings and learn about the nature of suffering,” she says. She began studying under the late Ruth Denison at her center in Joshua Tree, California, and is still practicing today.

Now a co-founder of the Institute for the Musical Arts in Goshen, Massachusetts, Millington continues to write songs, produce music, and mentor emerging musicians. While she no longer does yoga regularly, she still meditates regularly and practices Buddhism at home. “I remember my teacher Ruth Denison saying, ‘Make the world your cushion. Make the world your meditation,” she says. “So I try to make everything be in that frame of mind, and it has really worked.”