A look at the nationalism, militarism, and anti-Semitism of the Zen master whose teachings (through The Three Pillars of Zen and numerous disciples) place him among the most influential voices in the transmission of Japanese Zen to the West.

In Zen at War (Weatherhill, 1997), Brian Victoria examined how the Japanese Zen clergy interpreted Buddhist teachings in ways that made Zen dharma—and themselves—complicit with the Imperial Forces for the success of what was called “The Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.”

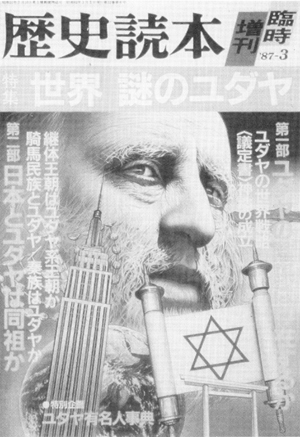

Recently, Victoria uncovered a specific text, a book that Yasutani Roshi wrote in 1943 about the thirteenth-century Zen master Dogen, in which Yasutani jingoistically employed fervent nationalism, obedience to the emperor, and anti-Semitism in his explication of Zen. These revelations raise questions that themselves are not new. But with the specificity of one person who figures so prominently in the Western expansion of Zen—whose face is so familiar to and revered by thousands of Western Zen students—comes a jarring, visceral kick in the gut that forces a confrontation with such issues as the nature of enlightened mind, the relationship between realization and actualization, and between form and emptiness; the constraints of time and place; and the alliance between political systems and forms of dharma—to name a few.

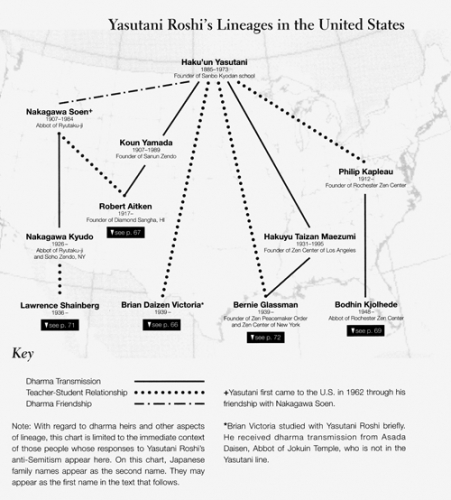

In this special section, Victoria presents and contextualizes material from Yasutani Roshi’s book on Dogen Zenji. This is followed by Victoria’s own response to the material. In addition, we requested responses from people directly descendent from or related to Yasutani Roshi’s lineages in the United States (see chart opposite below).

Yasutani Roshi: The Hardest Koan is not intended to answer the questions and paradoxes posed by Victoria’s material, but to initiate a conversation that may prove helpful, if not cautionary, to the unfolding of dharma in the West.

Introduction

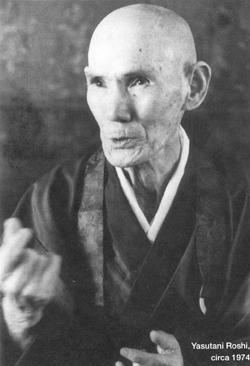

When we look at the recent history of Zen’s dissemination to the West—and in particular to the United States—it seems that the vast and varied terrain of the Zen landscape was funneled through just a handful of Japanese teachers. Of these, Yasutani Roshi (1885-1973) remains one of the most significant.

In 1965, Yasutani’s American disciple, Philip Kapleau, compiled The Three Pillars of Zen. The first section is devoted to Yasutani’s instructions for beginning students and continues to this day to be an essential source of Zen teachings. Although Yasutani traveled to the West seven times in the 1960s, it was largely this widely read and influential book that made him so important to the growing Zen movement. In addition to Kapleau, Yasutani was also a principal teacher of both Aitken Roshi and the late Maezumi Roshi. As a prominent lineage holder in three of the largest and most established Zen centers in the United States, Yasutani was a major player in the transmission of Zen from Japan to the West.

The Issue

Yasutani’s prominent role in the development of Western Zen provided ample opportunity to know this man’s personal history. But that did not happen. Yasutani’s support of the Japanese military establishment was ignored, denied, or diminished. Now, new research reveals Yasutani’s rabid anti-Semitism at the height of World War II if not before.

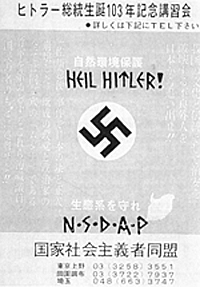

Anti-Semitism was part of a larger and complex picture of Japanese nationalism and the complicity of the Zen establishment with the Imperial forces (see Zen at War). It echoed German propaganda and certainly tapped into Japan’s own preoccupation with racial purity. Yet, in the absence of any sizable Jewish population, anti-Semitism was basically a mechanism to suppress liberal and left-wing thought among the Japanese themselves. That is to say, following the Russian Revolution of 1917 Jews had been portrayed in Japan as promoting progressive ideas in order to destabilize society and thereby further their insidious plot to take over the world.

Yasutani’s writings reflect all of this: support for the war; the interpretation of Zen teachings to deify the emperor, serve Japan, and wipe out the enemy; and the way in which Japanese anti-Semitism was tagged onto nationalism in order to counter all forms of ‘subversive thought.’

Given that Japanese anti-Semitism in 1943 was not central to nationalism in general or to Yasutani in particular, it is valid to question the intention in bringing this to light at all. My reasons address the resistance on the part of Westerners to confront the dark side of their tradition. Although there is, of late, some acceptance of how Zen teachings were used to encourage killing and mayhem, the massacre of Nanking, for example, does not pack the same emotional wallop for Westerners as the issue of anti-Semitism. Thus, these recent revelations provide a compelling point of entry to issues that continue to be relevant for anyone interested in Japanese Zen.

A look at the nationalism, militarism, and anti-Semitism of the Zen master whose teachings (through The Three Pillars of Zen and numerous disciples) place him among the most influential voices in the transmission of Japanese Zen to the West.

The Questions

Three Pillars of Zen was published just as the United States military was building its forces in Vietnam, and just as the counter-culture was building its forces against the government. Into this climate came a small wave of Zen masters, including Yasutani. It is not so difficult to see why young Americans wanted—even needed—to keep their Zen masters on pedestals, and keep under cover any information that related to Zen and the military. This said, it should be noted that the close relationship between Zen and the martial arts has seldom been questioned or regarded as problematic.

Now, however, the relationship of Japanese Zen to both war and the ‘warrior’ is under investigation, and the questions are profound and difficult. For starters, does Yasutani’s hate-mongering mock our respect for his enlightenment? Can words of genuine compassion and words of prejudice utter forth from one and the same person? Does one obliterate the other? To what extent can the embodied human—or the container for enlightenment—be expected to transcend parochial cultural values or aggressive nationalism? If we accept Yasutani’s subordination of the Buddha Dharma to the state, how does this change our experience of him as a teacher?

From Yasutani’s Book on Dogen

In February 1943 the firm of Fuji Shobo in Tokyo published a book written by Yasutani entitled: Zen Master Dogen and the Shushogi (Treatise on Practice and Enlightenment). The Soto Zen sect in Japan is founded on the teachings of Zen Master Dogen (1200-53). This book was published in the midst of what was literally a life-and-death struggle with the Allied Forces, chiefly the U.S. and Britain. Two months after the publication date, Yasutani, at age 58, received formal Dharma transmission from his master, Harada Daiun Sogaku (1870-1961).

The Purpose

Taking the view that the spirit of Japan and Buddhism are inseparable, Yasutani explains:

Those who would exclude Buddhism while seeking to exalt the spirit of Japan are recklessly ignoring the history of our imperial land and engaging in a mistaken movement that distorts the reality of our nation. . . . For this reason we must promulgate and exalt the true Buddha Dharma.

This, in turn, explains how a book on the great Master Dogen became, in Yasutani’s hands, a rallying cry for the unity of Asia under Japanese hegemony:

Annihilating the treachery of the United States and Britain and establishing the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere is the only way to save the one billion people of Asia so that they can, with peace of mind, proceed on their respective paths. Furthermore, it is only natural that this will contribute to the construction of a new world order, exorcising evil spirits from the world and leading to the realization of eternal peace and happiness for all humanity. I believe this is truly the critically important mission to be accomplished by our great Japanese empire.

In fact, it must be said that in accomplishing this very important national mission the most important and fundamental factor is the power of spiritual culture.

On the Spirit of Japan

Yasutani is one of a large chorus (see Zen At War) who supported the imperial forces with missionary zeal and presented Japan’s military and moral superiority as spiritual imperatives:

All the particulars [of the spirit of Japan] are taught by Japanese Buddhism. This includes the great way of “no-self” that consists of the fundamental duty of “extinguishing the self in order to serve the public [good]”; the determination to transcend life and death in order to reverently sacrifice oneself for one’s sovereign; the belief in unlimited life as represented in the oath to die seven times over to repay [the debt of gratitude owed] one’s country; reverently assisting in the holy enterprise of bringing the eight corners of the world under one roof; and the valiant and devoted power required for the construction of the Pure Land on this earth.

On Reverence for the Emperor

In Yasutani’s preoccupation with Japan and its military, Dogen’s emphasis on zazen and proper posture is reduced to a blueprint for unwavering moral rectitude serving as yet another manifestation of the spirit of Japan, the way of the warrior, and omnipresent “reverence for the emperor.” In the West, Dogen has most frequently been admired for his major work Treasury of the True Dharma Eye (Shobogenzo). He has been read for the sheer power of his poetic and lyrical statements on the nature of enlightenment, on practice, and on his extraordinary fascicle called “Being-Time” (Uji). Yet here, Yasutani lavishes praise on Dogen not for any of these, but for his alleged reverence for the emperor:

While it can be said that this is a feature of Japanese Buddhism as a whole, the great duty of reverence for the emperor is especially thoroughgoing in the Buddha Dharma of Zen Master Dogen, pulsing through its every nook and cranny. . . . He was consumed by his reverence for the emperor and concern for what he might do to ensure the welfare of this imperial land. If one thoroughly examines what Zen Master Dogen accomplished during his lifetime, it is clear that he was determined to cultivate the foundation of the people’s spirit, causing them to awake to the true spirit of Japan.

Yasutani on the Jews

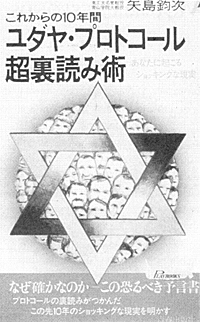

Everyone should act according to their position in society. Those who are in a superior position should take pity on those below, while those who are below should revere those who are above. Men should fulfill the way of men while women observe the way of women, making absolutely sure that there is not the slightest confusion between their respective roles. It is therefore necessary to thoroughly defeat the propaganda and strategy of the Jews. That is to say, we must clearly point out the fallacy of their evil ideas advocating freedom and equality, ideas that have dominated the world up to the present-day.

Beginning in the Meiji period, perhaps because Japan was so busy importing Western material civilization, our precious Japanese Buddhism was discarded without a second thought. For this reason, Japanese Buddhism fell into a situation in which it was half dead and half alive, leaving Japanese education without a soul. The result was the almost total loss of the spirit of Japan, for the general citizenry became fascinated with the ideas of freedom and equality as advocated by the scheming Jews, not to mention such things as individualism, money as almighty, and pleasure-seeking. This is turn caused men of intelligence in recent years to strongly call for the promotion of the spirit of Japan.

We must be aware of the existence of the demonic teachings of the Jews who assert things like [the existence of] equality in the phenomenal world, thereby disturbing public order in our nation’s society and destroying governmental control. Not only this, these demonic conspirators hold the deep-rooted delusion and blind belief that, as far as the essential nature of human beings is concerned, there is, by nature, differentiation between superior and inferior. They are caught up in the delusion that they alone have been chosen by God and are therefore an exceptionally superior people. . . .

The result of all this is a treacherous design to usurp [control of] and dominate the entire world, thus provoking the great upheavals of today. It must be said that this is an extreme example of the evil resulting from superstitious belief and deep-rooted delusion.

On the Precepts

As if providing us with a key to understanding his thinking, Yasutani included this comment on the First Precept, which forbids the taking of life:

What should the attitude of disciples of the Buddha, as Mahayana Bodhisattvas, be toward the first precept that forbids the taking of life? For example, what should be done in the case in which, in order to remove various evil influences and benefit society, it becomes necessary to deprive birds, insects, fish, etc. of their lives, or, on a larger scale, to sentence extremely evil and brutal persons to death, or for the nation to engage in total war?

Those who understand the spirit of the Mahayana precepts should be able to answer this question immediately. That is to say, of course one should kill, killing as many as possible. One should, fighting hard, kill everyone in the enemy army. The reason for this is that in order to carry [Buddhist] compassion and filial obedience through to perfection it is necessary to assist good and punish evil. However, in killing [the enemy] one should swallow one’s tears, bearing in mind the truth of killing yet not killing.

Failing to kill an evil man who ought to be killed, or destroying an enemy army that ought to be destroyed, would be to betray compassion and filial obedience, to break the precept forbidding the taking of life. This is a special characteristic of the Mahayana precepts.

—Brian Victoria

A look at the nationalism, militarism, and anti-Semitism of the Zen master whose teachings (through The Three Pillars of Zen and numerous disciples) place him among the most influential voices in the transmission of Japanese Zen to the West.

Brian Victoria Responds

The connection between Yasutani’s ideological stance and that of Japanese militarism is all too apparent. Yasutani in fact goes even further than the Japanese government of his day by asserting that his emperor-worshipping, pro-war, imperialistic, and anti-Semitic sentiments are nothing less than the “true Buddha Dharma.” In so doing it is no exaggeration to say that Yasutani had, consciously or not, completely subordinated himself to the state. That is to say, he not only rendered unto Caesar what was Caesar’s, but proffered the entirety of the Buddhist faith as well. Not only that, he urged all of the Japanese people to do the same.

It is exactly for this reason that I hold not only Yasutani but the Japanese Sangha as a whole, or at least its leading members, responsible for having slavishly and servilely promoted the state’s murderous agenda. This, however, does not absolve these leaders from individual responsibility for their acts, especially in light of the fact that there were a small number of Buddhist priests, lay persons, and organizations that, from as early as the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5, actively opposed, even at the cost of imprisonment and their very lives, Japan’s march towards militarism.

As is well known, Yasutani’s postwar writings, especially those introduced to the West, were notably free of the militaristic and anti-Semitic sentiments that characterized his wartime writings. To give but one example, in 1962 Yasutani described the precept on not killing as follows:

These days many voices proclaim the sanctity of human life. Human life should of course be valued highly, but at the same time the lives of other living beings should also be treasured. Human beings snatch away the lives of other creatures whenever it suits their purposes. The way of thinking that encourages this behavior arises from a specifically human brand of violence that defies the self-evident laws of the universe, opposes the growth of the myriad things in nature, and destroys feelings of compassion and reverence arising from our Buddha nature. In view of such needless destruction of life, it is essential that laymen and monks together conscientiously uphold this precept.

As admirable as these sentiments are, I find it difficult to shake the feeling that Yasutani was simply preaching what he thought his Western audience wanted to hear at the time. I say this especially in light of Yasutani’s ongoing postwar ultra-nationalist sentiments expressed in Japanese if not in English. In 1971, for example, Yasutani even went so far as to justify political assassination, i.e. when he wrote favorably about the October 1960 stabbing of Socialist party leader Asanuma Inejiro by a right-wing youth. Furthermore, when questioned by one of his American students in the 1960s about what to do in the event of being drafted for the Vietnam war, Yasutani replied: “If your country calls you, you must go.”

Yasutani and his like remind me of the weathervanes once so commonly found on barns throughout the U.S. These weathervanes “mindlessly” and “thoughtlessly” rotate in the direction of the prevailing wind, feeling no need to express the least regret for their previous orientations. Similarly, to the best of my knowledge, Yasutani never acknowledged, let alone repented for, his wartime exposition of the Buddha Dharma.

Finally, I would caution all those who regard themselves as “engaged Buddhists” against building their new movement on the foundation of a Buddha Dharma which has been emasculated to the point of denying some of its core teachings, especially those regarding non-violence. That is to say, those of us who identify ourselves as Buddhists must be aware of the ever present danger that we, too, might one day (if not already) be weathervanes for the self-interest of our country and/or the parochial interests of our society. In this respect at least, allegedly enlightened Zen masters like Yasutani truly have something very important to teach us.

Brian Daizen Victoria has been a Soto Zen priest since 1964. He is the author of Zen at War and currently lectures in the Centre for Asian Studies at the University of Adelaide in Australia.

Robert Aitken Responds

I respond as a student of Yasutani Haku’un Roshi, whose wartime militarism, jingoism, and prejudice Brian Victoria exposes. I think it is salutary for my practice and that of my students to drop off innocent adulation of living Buddhas and realize that our teachers are human after all, vulnerable to the social and political compulsions of their times. All of us owe gratitude to Victoria, to James Heisig, and John Maraldo for their book, Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School, and the Question of Nationalism, and to the scholars who are publishing a series in Zen Quarterly, the English language journal of the Soto Sect, disclosing the collusion of their sect in Japanese expansionism prior to and during World War II. These scholars help us as Western Zen students to make sense of the barest of hints of wartime involvement which we sensed previously, and to come to grips with the dark side of our heritage.

Unlike the other researchers, Victoria writes in a vacuum. He extracts the words and deeds of Japanese Buddhist leaders from their cultural and temporal context, and judges them from a present-day, progressive, Western point of view. The Japanese emperor has historically been at the center of Japanese society and all authority, however it has been delegated, has derived from him. Until the end of World War II, Japanese subjects were clearly Japanese first, and Buddhist—or whatever—second. They understood the will of the emperor to be their karma. Only a handful of Japanese could spring from such pervasive influence, and Victoria is harsh in judging the overwhelming majority who could not.

Yasutani Roshi spoke out vehemently against the Jews, but as Victoria notes, Japanese anti-Semitism has always been superficial. It has been a putrid flower with shallow roots, springing from a cultural aversion to the notions of individual freedom and social equality, rather than from the grotesque, age-old rationale that ignited European pogroms. It was delusive nonetheless, and I regret that my old teacher allowed himself to be caught up in it. Apparently his views changed, for in the 1960s he accepted students who had Jewish antecedents which they freely acknowledged. One of them, Paul Wienpahl, gives an endearing account of his study with him in his book Zen Diary (Harper and Row, 1970).

It is also disappointing to me to learn that Yasutani Roshi was publishing notably right-wing views at the end of his life. They did not seep into his teachings of the Dharma, which is where I focused when I was his student, nor did anyone in the English-speaking sangha ever mention them.

Moreover, despite his right-wing social views, it is clear that Yasutani Roshi came to regard nationalism as egocentricity written large. In 1967, he wrote:

Unenlightened people have this karmic illness of considering whatever they attach themselves to to have a self. If they make a group, they consider the group to have a self. If they attach themselves to the nation, they consider the nation to have a self. (Haku’un Yasutani, Flowers Fall: A Commentary on Zen Master Dogen’s Genjokoan, translated by Paul Jaffe, Shambhala, 1996, p. 49)

This is cogent Buddhist criticism of the conventional political world. It reflects a process of change in the Roshi’s views that should be balanced with his earlier benighted pronouncements.

Before its publication, I endorsed Zen at War, but asked the editor to have Victoria clarify or delete the last paragraph of the text. However, the book was published with the offensive paragraph unchanged. Here is the salient sentence:

Thanks to small numbers of pre-war leaders like Yasutani, it can be argued that modern-day variations of imperial-way Zen and soldier-way Zen are now to be found in the West as well as in Japan, although often without the knowledge or support of their Western adherents. (p. 191)

I am completely confident that any kind of variation of imperial-way Zen and soldier-way Zen would be totally unthinkable to Western sanghas that trace their heritage through Yasutani Roshi. Yet the passage as it stands indicates that we in Western sanghas are somehow unknowingly fascist. I have asked Victoria in two recent communications that he either retract or clarify the passage, and in both of his responses he acknowledged my request but evaded it completely.

Another factor is Yasutani Roshi’s character. He was often criticized by his own Japanese students for his intemperate words. It’s the way he was. Perhaps someone with analytical skills could like the anger he manifested in his political and sectarian pronouncements with the fact that his mother gave him up for adoption to a Buddhist priest when he was only five years old and that he then grew up to be an angry youth and adult. But the passion with which he expressed himself on secular subjects came through his teaching of the Dharma as well.

I am sorry to find such implacable condemnation in Victoria’s writing. I should like for him to acknowledge the pervasive power of culture and upbringing and the human potential for growth and change. The Buddha himself deepened his understanding of the Dharma in the decades following his experience under the Bodhi tree.

I remain grateful to Yasutani Roshi and to my other teachers. They gave me my life anew, and I dedicate my sutras to them and to their ancestors. Their sequence of appearance in my life was such that if any one of them had not been there for me at the opportune moment, I would not be sitting here in retirement from a career of teaching and writing. There would be no Diamond Sangha, with its centers and teachers in the Americas, Europe, and Australasia. Probably there would be no Buddhist Peace Fellowship as we know it. Soon after his death in 1973, Anne Aitken and I wrote a piece for the ZCLA Journal praising Yasutani Roshi for his “love and total generosity” as well as his “penetrating manner of teaching.” I stand by those words today.

A look at the nationalism, militarism, and anti-Semitism of the Zen master whose teachings (through The Three Pillars of Zen and numerous disciples) place him among the most influential voices in the transmission of Japanese Zen to the West.

Bodhin Kjolhede Responds

They took over half a century to reach us, but the revelations about Yasutani Roshi, like a long-range missile launched from the other side of the world, have hit the Western Zen community hard. The chief casualty: The Enlightened Person. Good riddance! Maybe now we can get out from his or her shadow and see that there has never been an Enlightened Person. There are only enlightened activities—that is, activities (or words, or thoughts) that do or don’t reflect a direct experience of the nondual nature of reality.

Once we unload the notion of a fixed person functioning out of a static state called enlightenment, we are freed of the glamour that overwraps the notion of enlightened selfhood and can focus on Yasutani Roshi’s words as a reflection of his understanding at the time. In one of the Buddha’s most oft-quoted statements, he warns us not to believe anything “on the mere authority of your teachers or priests” but instead to accept as true “whatever agrees with your own reason and your own experience, after thorough investigation, and whatever is helpful to our own well-being and that of other living beings.” Now, in Zen we learn that such an assessment is not always so simple. Gauging the truth of the written words of someone we’ve never met is tricky business, and all the more so when those words are a translation, with its author of a different culture and time. But the words of Yasutani Roshi in the record before us are anything but subtle or ambiguous. They boil with animosity and fury. Only someone blinded by identification with him would suggest that such sentiments could be in any sense enlightened.

Granted, the book he wrote that contained these virulent words came out in 1943, when he was fifty-eight, which was before he received dharma transmission and long before he became known to Westerners through The Three Pillars of Zen. Perhaps he had subsequent awakenings that knocked out those wedges of enmity. We know that in the next decade he embraced Philip Kapleau (whose mother, incidentally, was Jewish) as a disciple, and, by the latter’s account, was immensely generous toward him with his time in dokusan and in collaborating on The Three Pillars. We also know that Yasutani Roshi repeatedly journeyed to the United States and inspired other American students. But then there was his knee-jerk support of the Vietnam War, and his rabid anti-Communism, both still intact shortly before he died.

Now that we’ve had the book on Yasutani Roshi opened for us, we are presented with a new koan. Like so many koans, it is painfully baffling: How could an enlightened Zen master have spouted such hatred and prejudice? The nub of this koan, I would suggest, is the word enlightened. If we see enlightenment as an all-or-nothing place of arrival that confers a permanent saintliness on us, then we’ll remain stymied by this koan. But in fact there are myriad levels of enlightenment, and all evidence suggests that, short of full enlightenment (and perhaps even with it—who knows?), deeper defilements and habit tendencies remain rooted in the mind.

“But surely,” we protest, “a Zen master of Yasutani Roshi’s stature would be enlightened enough to have eradicated character defilements as gross as warmongering and anti-Semitism.” One would have thought so. There is little doubt that Yasutani Roshi had realized, to some degree, the nondual nature of reality. How, then, can we understand his vitriol of division? Since he didn’t come into the world with notions of “us” vs. “them,” he had to have acquired them through the process of social, political, and other conditioning.

A reading of Japanese history in the several decades following the Meiji restoration (1868) reveals a populace gagged and blindfolded by the government and subjected to nearly total thought control and indoctrination. Internal security laws against intellectual freedom were severely enforced, and the resulting information vacuum was filled with official militarism, which was grounded in the state-dominated public educational system. This standardized system, under which neither teacher nor parent could make any choices for the student, inculcated total submissiveness to the militaristic authority and an awed obedience to the emperor, overwhelming a critical consciousness toward war.

Yasutani Roshi was formed by this educational system and became a product of it even more so than his contemporaries, for he became a schoolteacher himself. By the time he entered teacher training school at age twenty, every single subject in the national curriculum was oriented to war and patriotism. He continued to be a schoolteacher and then a principal until he turned forty and changed his career to that of a Zen priest. We may conclude, then, that as a student Yasutani Roshi was so wellforged in the national militaristic education mold that he went on to become the hammer and tongs himself.

Like so many other Japanese Zen men of his time and before, Yasutani Roshi did not see himself as subordinating the Buddha-dharma to the state, because he saw these as two aspects of the same truth. This notion of religion and state as one had gathered steam in China during the Sung dynasty and later was absorbed into Japanese Zen, ready to assume its most patriotic and militaristic form in the nationalistic milieu of Yasutani Roshi’s time. By then the destruction of the Japanese nation was seen even by Zen masters as tantamount to the destruction of the Buddha realm, so much so that the Japanese military chose December 8 (December 7 in Hawai’i), the Buddha’s Enlightenment Day, to bomb Pearl Harbor.

To learn of the historical, educational, and political conditioning in which the Japanese of Yasutani Roshi’s time were swathed from birth is to be somewhat amazed that any of his peers, including Buddhist priests, would have hesitated to rally to the government war drums beating so loudly and insistently. Moreover, Yasutani Roshi’s wartime rhetoric, like all war cries, was laced with fear, but it was so uninhibited and unabashed that we have to acknowledge its utter sincerity.

The revelations about Yasutani Roshi left me disappointed, even troubled, but not shocked. His teachings have inspired me throughout my Zen career, but there have been too many Buddhist teachers implicated in gross misconduct over the past couple of decades for us to be able to entertain exalted assumptions of anyone, even our esteemed seniors. Besides, I had long ago made peace with the bellicose side of Yasutani Roshi’s personality. I never met him, but had been exposed to bits of his writings, which were marked by their share of piss and vinegar. Like the Japanese Zen master Hakuin, he seemed to relish denouncing those he saw as enemies of the dharma, inveighing against this teacher, that scholar, the whole Soto Zen establishment in Japan. After getting past my early idealization of him from The Three Pillars of Zen (and my own teacher’s obvious profound gratitude to him), I came to see him as more than a little rigid and authoritarian—a kind of Zen fundamentalist: the Ayatollah Yasutani. When I described this impression of him to Kapleau Roshi, it surprised me to hear that he had always found Yasutani Roshi to be gentle, soft-spoken, and laid-back, in contrast to his first teacher, Harada Sogaku-roshi. But after Kapleau Roshi moved back here from Japan in 1966, and was then authorized by Yasutani Roshi to begin teaching, the two soon found themselves at odds over what could most simply be summed up as issues of authority. Kapleau Roshi acknowledges his share of responsibility in the painful break between them that resulted, but I wonder—what if he had learned of Yasutani Roshi’s over-the-top wartime sentiments while he was training under him in Japan? Would their break have come earlier?

The most compelling task for those of us sobered by the revelations about Yasutani Roshi is to turn our attention back to ourselves unflinchingly. What collective assumptions and mental attachments do we share that are causing us even now to corrupt the dharma? Ours is a society intoxicated with individualism, choice, and comfort. As a people we tend to be insufferably moralistic, dismissive of the integrity of tradition, and to have a knack for debasing religion (and most everything else) through self-promotion and commercial hype. And these are just some of the major threats we face in adapting the Buddha’s teaching to our country. So let us reject the politics of Yasutani Roshi and commit ourselves to the timeless, universal practice to which he devoted his life.

Bodhin Kholhede is the dharma heir of Philip Kapleau Roshi and has been abbot of the Rochester Zen Center since 1986.

Lawrence Shainberg Responds

Even if Yasutani’s anti-Semitism weren’t the product of a culture, a language, and a period in history that is totally foreign to me, I could never know what prompted him to make these unforgivable remarks. What I do know is that, not many years after he made them, he was leading sesshins in New York at which, incidentally, many participants were Jewish. Those of us who—thanks to the generosity and wisdom of teachers like Yasutani, his close friend Soen Roshi, and his disciples, Maezumi, Eido, and Kapleau Roshi, among others—have been fortunate enough to experience this particular spiritual practice know that it brings together a group of people for extended periods of Zen meditation, or “zazen.” The rules of sesshin—don’t speak except when absolutely necessary, don’t disturb your fellow practitioners, watch your own mind instead of blaming or judging others—are ingeniously designed to facilitate unobstructed confrontation with oneself. Most of those who participate in such practice find themselves almost unbearably humbled by the awareness it engenders, the light it casts on the chaos and tyranny of one’s neural circuitry, its endless capacity to produce anger, paranoia, simple-minded explanation, self-hatred, and narcissistic grandiosity, as well as clarity, equanimity, and compassion. From moment to moment, one never knows whether one will be overcome with feelings of absolute union with others or seized up and salivating with the sort of me-versus-you or we-versus-them histrionics that Yasutani displays in these paragraphs. It’s as if the practice releases an energy that so threatens the habit of one’s dualistic mind that the latter, in a sort of immune response, produces thought that has no purpose other than undermining and contradicting it. Any Zen student, beginning or advanced, knows this equation: The practice doesn’t eradicate delusion so much as create an awareness of it that, in turn, makes the practice more essential and more desperate.

If my experience is any guide, the great Zen teachers are not those who are free of this equation but rather those who are most aware of it and so most desperately committed to the practice. They practice, as Hakuin Zenji put it, “as if trying to escape from a vat of boiling oil.” Maybe there are Zen students who did not, like me, come to the practice with a pack of sanitized, romantic, materialistic, and egoistic expectations, but if you’ve shared my misunderstandings, you will know that there is nothing like an encounter with such desperation for correcting them, and nothing like such correction for offering you at least a glimpse of truth beyond the habit of your psychology.

I never had the luck to study with Yasutani Roshi, but I know from those who did that he brought this gift to them as they in turn have brought it to me. Forgive me if I find it impossible to separate such gifts from the ignorance of his anti-Semitic remarks or to ignore the fact that, if a man of his stature emerged from such miserable delusion, there may be hope for me. I’d kick his ass if he made such statements in my presence, but what I feel for them at this remove is something very close to gratitude.

A look at the nationalism, militarism, and anti-Semitism of the Zen master whose teachings (through The Three Pillars of Zen and numerous disciples) place him among the most influential voices in the transmission of Japanese Zen to the West.

Bernie Glassman Responds

Yasutani Roshi’s 1943 writings and the questions they raise remind me a little bit of what happens during the Zen Peacemaker Order’s annual retreats at the death camps. Every year there are several German participants who tell similar versions of the same story: A man took part in terror and mass extermination in the 1940s, and then proceeded to have a family whom he loved and who loved him in return. Sometimes it’s a beloved grandfather, sometimes a cherished great-uncle. The unspoken—and sometimes spoken—question that hovers around these stories is: How can all this be harbored in one human being? How can one person inflict that much suffering and earn that much love?

In Yasutani Roshi’s case, we can formulate the question in this way: How could a Zen teacher acknowledged by many to be one of the great Japanese Zen masters of this century, deeply admired for his enlightened mind and earning the special gratitude of American practitioners for bringing Zen teachings to this country, how could that man articulate such views?

As we bear witness to this phenomenon, we first and foremost bear witness to our own disbelief, our own shock and incredulity, which arise from our own concepts about enlightenment.

So what is enlightenment? Who is enlightened? Is someone espousing Nazi propaganda enlightened? According to my understanding of enlightenment, I am enlightened. According to the understanding of my teacher, Maezumi Roshi, I am enlightened. I’ve never met Shakyamuni Buddha, never had any personal dealings with him, but according to what I’ve read about him, I believe that he would have said that I am enlightened. And that’s for the reason that, upon the occasion of his great realization, he said: “How wonderful! All sentient beings, as they are, are enlightened!”

Not everybody believes as I do. I think that most people who’ve met me probably wouldn’t say that I’m enlightened. There are Buddhist teachers, many of whom I respect, who believe that what the Buddha meant was that everyone has the potential to be enlightened. Some believe that it takes many, many lifetimes to reach a state of realization.

Nevertheless, what I’ve learned from my teacher and what I’ve taught my own students is that all of us are one body. We are the stars, the moon, the trees, the death camps, the killers, and the killed. We are enlightenment and we are delusion. We read it, we say it, but we don’t believe it. So the experience of realization is seeing and realizing exactly that—that everything is enlightened as it is. That all of life is the enlightened state, that all of life is one body. And that it is constantly changing.

Actualizing that realization means that we live our life out of the realization of the oneness of life, out of the understanding that this is it. Of course, all of us are actualizing who we are all the time. All of us have some degree of realization and, moment after moment, are manifesting our understanding of the oneness of life. Obviously, the greater the realization, the greater the clarity, the greater the confidence.

And with all that, even while possessing great realization, we still have our conditioning, our own particular characteristics, our own particular paths. Little of that changes overnight. In fact, there is a great deal that remains unchanged throughout one’s lifetime. We acquire from a very early age strong patterns of behavior; we have physical characteristics that we and others sometimes call limitations; we have traits embedded in our DNA that we are powerless to change in this lifetime. It is like drinking from a glass and then washing it of all trace. The washing itself leaves traces. So we wash some more, try different ways of cleaning and drying, yet no matter what we do, some trace is always left.

That is why, in our lineage, we believe so strongly in Continuous Practice. Say you have a realization of the oneness of life. If you stop right there, thinking there’s nothing more to grasp, your conditioned ways of doing things “‘ill soon take over once again. But if you continue to practice after the initial enlightenment experience, it will continue to unfold and broaden, deepening to the very end of what we call our life. That’s what we call Continuous Practice.

I have often noticed that students of the Way, knowing full well that Shakyamuni Buddha taught that everything is change, seem to think that that is true about everything but the state of enlightenment. As if everything changes other than the realized mind. As if, once you have had such an expelience, you are frozen in that state.

I didn’t know Yasutani Roshi in 1943. From what I know of his life story, 1943 marked the end of some eight years of serious training with Harada Roshi. Prior to those studies he had been a temple priest and a high school teacher; he would have probably been the first to say that till meeting Harada Roshi, he had been blind. In 1943 he received dharma transmission and wrote the book that contained these writings. I don’t know why he wrote them. He might have written them without believing in them, simply because he needed to placate the powers that be. Historically, that has certainly been true of many other teachers and religious leaders. He might have made them believing fully in what he wrote. Had we met at that time, knowing what he wrote, I would probably have had no interest in studying with him.

But I met him in 1967, both in the zendo, in dokusan, and in a more relaxed social setting in my role as Maezumi Roshi’s attendant. As a Jew, I never picked up a hint of bigotry against the West in general or against Jews in particular. After receiving dharma transmission, Yasutani Roshi continued to practice, and finally, the same man who had believed so much in the spirit of Japan now believed equally in transmitting the teachings to the West, including to Jews. So I imagine that something must have shifted in him, something changed. And why shouldn’t it? Things change for all of us. I have made statements twenty and thirty years ago, during the time of my own dharma transmission, before and after experiences of realization, that I would not make now. I was enlightened then and I am enlightened now. And my understanding grows with the years, as it does for everyone who continues to practice. We have many delusions about enlightenment. One delusion is that the realized mind doesn’t change, doesn’t grow after the realization experience.

An associated delusion has to do with the idea that there are no delusions after an enlightenment experience. A cornerstone of Alcoholics Anonymous is that alcoholics are alcoholics to the end of their lives. They may not be drinking all that time. They may not be drinking for thirty, forty, even fifty years. Still, they are alcoholics. The same is true in Zen. I’ve often begun my talk in front of an audience the way they do in meetings of AA: “Hello, my name is Bernie, and I am an addict. I am addicted to my ego. I have always been addicted to my ego and I will always be addicted to my ego.”

We are addicted to our self-centered identities for all time. That doesn’t mean we don’t practice. That doesn’t mean we don’t have realization experiences. That doesn’t mean we’re not accomplishing the Way. And simultaneously we are addicted. And the addiction—and the practice—go on forever.

Many people don’t buy that. They seem to think that delusion is outside the enlightened state. But if we truly see that we are all One Body, then that One Body includes enlightenment and it includes delusion. It includes everything. To understand the One Body, think of a circle. There can be nothing outside that circle. If there is one thing that you can think of that is outside that circle, one delusion that you cannot permit inside that circle, then I suggest that you change your definition of the circle to include that one thing as well.

So if your definition of enlightenment is that there’s no anti-Semitism in the state of enlightenment, you better change your definition of enlightenment. If your definition of enlightenment is that there’s no nationalism, or militarism, or bigotry in the state of enlightenment, you better change your definition of enlightenment. For the state of enlightenment is maha, the circle with no inside and no outside, not even a circle, just the pulsating of life everywhere.

At one time in his life Yasutani Roshi supported war and wrote bigoted statements concerning the West, the United States, and Jews. After receiving dharma transmission from his teacher and father, Baian Hakujun Roshi, my teacher, Maezumi Roshi, continued his studies with other teachers, including Yasutani Roshi, and finally received Yasutani’s seal of approval to teach in 1970. I also studied with Yasutani Roshi in the Zen Center of Los Angeles. His best-known Western student was a Jew, Philip Kapleau. Most of us had and continue to have deep admiration for his understanding of the dharma and the compassion and commitment that he manifested by taking long trips to lead sesshins in America at a very advanced age. We could say that, according to our concepts of good and bad, right and wrong, his state of realization had deepened over the years. It’s important to see how subjective that statement is.

My teacher, Maezumi Roshi, died in 1995. At the time he died he was reading Primo Levi’s Survival at Auschwitz. Was I moved when I heard that? Yes. Was my response to that quite different from my response to Yasutani Roshi’s 1943 writings? Definitely. Is one more enlightened than the other? No. Each simply actualized his understanding in a different way.