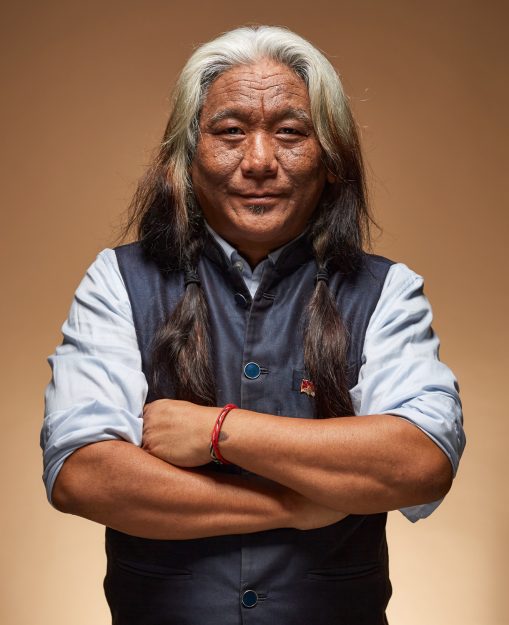

Tenzin Choegyal, one of the world’s finest Tibetan musicians, says that as a child he always woke up to the sound of his mother chanting. It might start as early as four in the morning, while he was still dreaming. Throughout the day, he would remain immersed in her voice as she sang while doing chores. The singer and composer considers his mother a strong influence in his 20-plus-year music career, and he named his newest album, Yeshi Dolma in her honor.

Choegyal has performed around the world, has opened for public talks by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and he has made nine studio albums. He has also partnered with world-renowned artists including Phillip Glass and Patti Smith, and in 2019, he released Songs from the Bardo, a musical interpretation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, with Jesse Paris Smith and Laurie Anderson. His music brings together the unmistakable traditions of Tibet with inventive, genre-transcending sounds that create a profoundly meditative and heart-opening experience for listeners. In addition to his soul-stirring voice that evokes the nomadic musical lineage of his ancestors, Choegyal’s instrumental repertoire includes the dranyen, a traditional Tibetan stringed instrument; a ling-phu, or Tibetan flute; singing bowls; a gong; and many experimental instruments, including rocks.

His latest album is a collaboration between himself, his friend, composer and cellist Katherine Philip, and Camerata, Queensland’s Chamber Orchestra. I recently sat down with Choegyal to discuss his journey as a musician, the interconnection of dharma and music, the Tibetan refugee experience, and the inspiration for Yeshi Dolma.

Can you tell us about your early life and how you became interested in music? I was born in Tibet. In the early 1970s, the Cultural Revolution was happening in Tibet and many Tibetans were coming out. My parents came out through the Mustang region of Nepal when I was just a toddler. My parents were nomads and had nine kids. Five of them survived. My father passed away and my mother became a single mother with lots of kids. So she sent me to live at the Tibetan Children’s Village in Dharamsala, India. It was the story of being a refugee at the time, for Tibetans. All of your parents and relatives and friends were scattered around the globe.

I would say that my closeness with the nomadic lineage of songs and sounds is from the imprint of hearing them as a child. Playing the flute is definitely my father’s influence. I don’t really remember his facial features, but I remember his flute playing quite well. Hearing him play definitely inspired me to learn more. My mother’s voice is also instilled in me. She was like many of the Tibetan elder generations who would wake up very early in the morning and just out of faith, start chanting. I always woke up hearing my mother’s chanting, around maybe four in the morning, while I was still in the dream state. She would also always sing songs while doing chores. Also being around the elder generations of Tibetans—Tibetans are so spontaneous at singing. But definitely [my interest in music] comes from the hearing empowerment of my parents.

How did you ultimately become a musician? While I was growing up at the Tibetan Children’s Village, I was in the school choir and took part in house competitions. I remember one time when I was singing with a lot of other students, and the teacher took me aside and said, “You have a very beautiful voice, but maybe you don’t have to come [to practice] anymore.” I must have been singing super loudly or something like that (laughs).

At school in the evenings, a couple of friends and I would jump on this makeshift stage and sing to the classroom, just for fun. There were no performances or anything. But somehow, growing up in that school, I always told my teachers and friends that I wanted to be a musician when I grew up. Even though there were no role models or anything like that.

Then, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Dharamsala was a hub for hippies. We would have these amazing tourists visiting from all over the globe, and they would bring all of this beautiful music. The Doors, the Beatles, sometimes classical musicians—people who wouldn’t have easily gotten to Dharamsala otherwise. They would play it in cafes and hippie gathering places. So, I think that had an influence on me, too.

How does Buddhism impact your creative process as a musician? I think music is a practice, you can make it a dharma practice. It is not some different entity from me. I am super inspired by all these treasures we have in the Tibetan Buddhist world. I try to bring a little of that into my music.

In the Tibetan tradition, there were yogis who were into music. Milarepa sang all his teachings. In the monasteries, they produce all of these beautiful sounds, and all the texts are read in melodic chanting. That’s also music.

I also love the simplicity of the mantras when you repeat them. I had a beautiful experience of that when I traveled to trace the path my parents took out of Tibet when they left. I was reciting the mantra with the bell sound of the horse that I was riding, the sound of the mountains, and the spaciousness of it. There was a special moment where it hit my mind, just a couple of seconds, and then went away. I hold that experience dear to me and when I need inspiration, I go back to that internal space.

So the Buddhist practice is in my music. It’s always there.

Your new album, Yeshi Dolma, is actually named for your mom, right? Yes. Yeshi Dolma is my mother’s name. There is a song on the album with that name, which is an old traditional song from Tibet. Lyrically, it was different, but I changed the lyrics and kept the essence of the Yeshi Dolma song. We put it together and it’s got lots of harmonics in it and the string arrangement.

The album is giving homage to her and her generation of Tibetans who have gone through so much. Her generation was always ready to go back home to Tibet. If you went into a Tibetan elder’s house in the 80s or 90s, their homes were super well packed in boxes. They were never settled in the place where they had taken refuge. They were always ready to head back home whenever. My mom was one of them, and [my parents] passed away in exile. So it’s a tribute to them and saying, “We remember you. I remember you.” A bittersweet way of paying homage.

Can you tell us any more about the meaning of the album? Yeshi means “wisdom” and Dolma is the goddess Tara. The first piece in the album is “Dolma” and in the middle there is “Yeshi Dolma.” There is a little string attached to each song in a way, as they go into each other. It’s like the story continued and it has the feeling of an unfinished story. When we were organizing the flow of the tracks, we started with the first song, “Dolma,” being just the strings and then the next is “Nomad Song,” which pays homage to my own lineage. And then in the middle is “Snow Lion.” I wrote that when I was traveling in Japan in 2008 and the Beijing Summer Olympics was happening. There were many stories coming out of Tibet at that time and we didn’t know what to do. So that song was an expression of wanting to be like the snow lion, with fearlessness in facing obstacles. I was visiting a lot of Japanese temples at the time and every time I went to a temple, there were two snow lions at the front gate.

Is there anything you’re hoping the listeners will experience when they hear the album? For me, I’m super open to how the listeners interpret their own stories to it.

♦

Watch a performance of “Snow Lion” from the album Yeshi Dolma, with Camerata – Queensland’s Chamber Orchestra.