OUT IN THE MIDDLE of the Midwest flyover zone, where cornfields part for a moment to reveal the tiny village of Yellow Springs, Ohio, a Sri Lankan monk came to spend his annual retreat last fall with a group of Western Buddhists. Bhante Seelagavesi may not have known it, but his unusual and mildly rebellious approach to teaching was a perfect match for the unusual and mildly rebellious character of the town and the liberal Antioch College that anchors it. The Yellow Springs Buddhist community did not expect it, but the initiative and support it gave to host its first three-month retreat for an ordained monk of high rank attracted more people than the twelve-year-old Yellow Springs Dharma Center had ever seen.

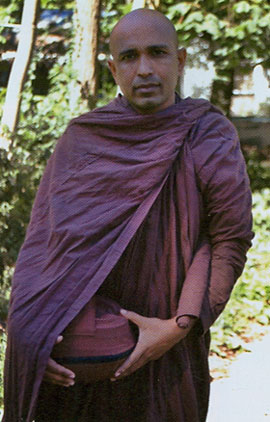

Seelagavesi, bald and barefoot, robed and devoted, is no run-of-the-mill monk. His path toward awareness is not blind acceptance but finding purpose in the rituals he practices. Offering food to the Buddha for merit, for instance, has no meaning for him. “I have never seen the Buddha eating this food, so why should I give him it?” he asks. Yielding as a rule to monks of highest rank he feels undermines the will and responsibility of younger monks. So he doesn’t usually do that, either.

While Seelagavesi’s ways have sometimes drawn criticism in Sri Lanka, his inclination to question everything attracted Antioch students Cindy Eigler and Alison Easter when they traveled to Sri Lanka with the Antioch Buddhist Studies Program in 2002. Seelagavesi’s take on Buddhist practice seemed to fit nicely with the academic approach students and others in Yellow Springs have taken toward the dharma.

But when the students suggested the monk spend his retreat in Yellow Springs, a village of 3,700 people, the Dharma Center board wondered whether its fifty core members could sustain such a long and committed retreat. Where could he live and be afforded the privacy and respectful accommodations he merits? Who could attend to him and prepare the food that he can only eat once a day and is not permitted to ask for? How would it all be paid for? Could a completely Western center really support a traditional monk? The answers came from the younger generation of Yellow Springs Buddhists.

Robert Pryor, director of the Antioch Buddhist studies program, co-founded the Yellow Springs Dharma Center with local resident Donna Denman, to serve Buddhists from various traditions as well as yoga and general meditation practitioners. The center has been sustained by a generation of Western Theravada and Zen Buddhists now in their fifties and sixties who have shared their practice with Antioch students. Today the younger students are challenging the sangha to engage in Buddhist activities the center has never tried before.

Dharma Center board member Amanda Bilecki, who became a Theravada Buddhist as a student in the Buddhist studies program, rallied the local sangha to prepare for the retreat, and Eigler and Easter recruited a young friend, Kaanchan Adhikary, to act as Bhante’s twenty-four-hour attendant. The sangha paid for a room at the center for Bhante and Adhikary, and asked local community members to provide food, transportation, and financial support to make the program a success.

In addition to teaching the dharma, Seelagavesi introduced a healing technique to the community, uniquely his, that treats both mind and body through chanting Buddhist scripture. By focusing on his patients with compassion, Seelagavesi said he could “open their hearts,” identify their ills, and prescribe chants that would help them to heal both physically and mentally.

“I look at the eyes and send my mind to the body and find the imbalance in the mind or body,” Bhante said. “But I don’t want only relations with the unhealthy world. I want to see healthy people who come to find freedom with meditation. That is compassion. That helps others to have determination to be healthy.” For the first month of the retreat, activity at the Dharma Center was focused on the core group of local Buddhists. But word about Seelagavesi’s penetrating and insightful character quickly spread, and dozens of people from Yellow Springs and the surrounding area whom Bilecki said she had never seen were coming to see the monk for healing and guidance.

Westerners weren’t the only people who responded to his lessons and his healings. Lakshman Gunawardena, who came to the U.S. from Sri Lanka five years ago, drove twelve hours from New Jersey with seven friends and family members to meet Seelagavesi at the Dharma Center in September. He was surprised to see so many Americans practicing the dharma, he said, and he was touched by their serious devotion, which seemed to be lacking in his own Buddhist center in New Jersey.

“I am a Buddhist, but I don’t get what I want from [my] center,” he said. “It’s too busy and not focused on meditation. People come there to talk and socialize.”

Gunawardena also said he had never seen a monk on retreat in the U.S., and that Bhante’s atypical use of psychology in explaining the application of the dharma resonated strongly with him. “The way Bhante speaks to your heart, he talks about real life, how your mind reacts and how to get out of it,” he said. “The people like him because he talks the truth. We go there to get relief from stress and get solutions to problems.”

There is very little difference between American and Sri Lankan people’s devotion to the dharma, Seelagavesi said of his retreat. But, he noted, whereas Sri Lankans naturally depend on each other for their needs and can therefore easily trust his treatments and advice, Americans, because they value independence, must develop humility before they can learn to trust and rely on the dharma.

American Buddhists are also strengthened by their independence, which teaches them to question, as Seelagavesi does, the reasons for their actions. It also teaches the younger generation how to take leadership roles, as those in Yellow Springs are doing, to grow the Buddhist community and make the practice available to everyone. In her heart, Bilecki knew from the start that the challenge of bringing Bhante to Ohio was worth it.

“I have tremendous confidence that making the opportunity available for people is its own reward,” she said. “I did this because I love the dharma, and it’s been my experience that practicing, especially under a gifted teacher, is more transformative than any other activity I’ve ever undertaken.”