Buddhists have always told stories of the dharma’s transmission to new cultural settings. The translators, yogis, scholars, teachers, and pilgrims who carried the tradition from one context to another are told of in chronicles that speak not only of events but also of experiences. Which is to say, these narratives of transmission are themselves part of the process that they describe. They connect their readers with an ancestral past by bringing that past to life in the present.

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of Rick Fields’s masterful How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, a story Rick weaves with eloquence, insight, breadth of vision, and an abundance of human warmth. The Buddhist landscape has of course changed a lot in the time since the original edition, with the intervening years bringing new stories in need of telling and new perspectives in need of inclusion. Still, Swans remains an irreplaceable resource and a foundational text. It is also, as it should be, a great read.

Rick did much of the research and writing during the two or three years he lived at and around the Zen Center of Los Angeles, which is where I got to know him. He once told me how unprepared he was at the project’s outset, thinking that he could complete the manuscript in just a couple of years. But as he proceeded, the story kept growing—that is, to tell about this thing, he had to go back to that thing; to tell about that thing, he had to go sideways and bring in this other thing. The endpoint had a way of receding with each step forward.

When the book neared completion, Rick and I talked about how we might mine the manuscript for an essay or two in the Zen Center’s journal, The Ten Directions. The following article is what we came up with. It tells the story, drawn from Swans, of D. T. Suzuki, perhaps the single most influential figure in bringing Buddhism to the West.

A word about Rick himself. He was, as much as anyone can be said to be, the originator of Buddhist journalism. Not incidentally, his many and varied contributions were from the start an instrumental support to Tricycle.

I don’t think anyone who knew him would mistake Rick for a saint, but all would agree that he was a real character who got around. He could tell a story and just as likely he could be the story. One of my favorite bits of Fieldsiana comes by way of a Zen friend from long ago, who had a lunch date at a diner somewhere up in the Bronx with a woman he had not met before. At some point, he mentioned a guy he knew, a Buddhist writer named Rick Fields.

“You know Rick Fields?” she said. “I know Rick Fields!”

At that, someone at the next booth looked over at them and said, “You folks know Rick Fields? I know Rick Fields!”

When Rick passed away, from cancer, in 1999, I thought about this exchange. It would, I figured, now be echoed across buddha-fields and through world systems, in capitals and provinces, in Pure Lands and saha realms without number, in temple gardens and coffee houses and great libraries and intimate nightclubs and wherever else in the infinitude of space and time bodhisattvas get together to take a break to relax and chat.

“You know Rick Fields?” they are saying. “I know Rick Fields!”

—Andrew Cooper, Features Editor

Soyen Shaku (1860–1919), abbot of Engakuji, the renowned Rinzai Zen temple in Kamakura, Japan, was the first Zen master to visit America. He appeared in August 1893 at the World Parliament of Religions held in Chicago. The Parliament drew together representatives of many faiths, including Swami Vivekananda, founder of the Vedanta Society, and Anagarika Dharmapala, founder of the Maha Bodhi Society. Soyen Shaku’s talk, “The Law of Cause and Effect, as Taught by Buddha,” emphasized the scientific nature of the dharma at a time when the “rationalism” of Buddhism seemed one of its most appealing features. His paper had been translated at Engakuji by a young lay student, one Teitaro Suzuki.

Of all the acquaintances Soyen Shaku made at the Parliament, none was to prove more important to the development of Buddhism in America than the German émigré Dr. Paul Carus, editor of the philosophical journal The Monist and Open Court Press, an early publisher of Asian religious texts. Carus thought that Buddhism was more fitted than Christianity to heal the breach between science and religion, since it did not depend, he believed, on miracles or faith. Soyen Shaku’s talk on cause and effect supported his views, and after speaking with the Zen master, Carus invited him to his home in LaSalle, Illinois, a small town some seventy miles southwest of Chicago. There Carus proposed that Soyen help him translate and edit Open Court’s new series of Asian works, but Soyen refused the offer. (He was, after all, the abbot of an important Zen monastery.) He suggested in his stead his student Suzuki.

Teitaro Suzuki was born in Kamazawa, a town two hundred miles north of Tokyo, in 1870. His father was a physician with a fondness for the Chinese classics. His privileges as a member of the samurai class had been abolished by the Meiji restoration, and Suzuki grew up in a kind of genteel poverty. His father’s death in 1876, when Suzuki was only six, made the family’s situation even more difficult. Teitaro Suzuki found a job teaching arithmetic, reading, writing and English in a small fishing village. (He had taught himself English from books.)

After his mother died, Suzuki made his way to Tokyo and the Imperial University, where he took courses and began to wonder about this karma—why his father had died while he was still young, and why he had started life with so many seeming disadvantages. His family belonged to the Rinzai school of Zen, as did most samurai, and thus it was natural that he turn to Zen for an answer to his questions.

“I remember sitting in a field thinking that if I could not understand Mu life had no meaning for me.”

Suzuki did not become a monk, but as a lay disciple he lived the strict life of a novice monk at Engakuji, where he shared living quarters with the young monastic Nyogen Senzaki, who would become another major proponent of Zen in the United States. In 1892, Suzuki began studying under Soyen Shaku, newly installed as abbot, who gave the young scholar the koan Mu. “I was busy during these years,” Suzuki remembered nearly seventy years later, “with various writings, including translating Dr. Carus’s Gospel of Buddha into Japanese, but all the time the koan was worrying at the back of my mind. It was, without any doubt, my chief preoccupation, and I remember sitting in a field leaning against a stack of rice and thinking that if I could not understand Mu life had no meaning for me. . . . After finding that I had nothing more to say about Mu I stopped going to sanzen (interviews) with Shaku Soyen, except for the sosan, or compulsory sanzen during a sesshin. And then all that usually happened was that the Roshi hit me.”

“To solve a koan,” Suzuki later wrote, “one must be standing at an extremity, with no possibility or choice confronting one. There is just one thing one must do.” Suzuki’s spiritual crisis came about when it was finally settled that he would go to the United States to work with Carus. “I realized,” he said, “that the Rohatsu sesshin that winter might be my last chance to go to sesshin and that if I did not solve my koan then, I might never be able to do so.” Suzuki put all his spiritual strength into the sesshin, and finally, toward the end of the fifth day, when “there was no longer the separateness implied by being conscious of Mu,” a bell sounded, he was awakened from his samadhi, and he answered all of Soyen Shaku’s questions except one. The next morning, he answered that one too. He remembered that night, walking back to his quarters in the temple, “seeing the trees in the moonlight. They looked transparent and I was transparent too.”

Soyen acknowledged Suzuki’s realization by giving him the lay Buddhist name “Daisetz,” which means “Great Simplicity” (in his later years, Suzuki liked to tell people that it meant “Great Stupidity”). Soon arrangements were made for him to go to America and begin work with Carus. “My Dear Friend and Brother,” Soyen Shaku wrote Carus from Kamakura on February 2, 1897, “T. Suzuki will leave Yokohama by the steamer ‘China’. . . . He is an honest and diligent Buddhist, though he is not thoroughly versed with Buddhistic literature, yet I hope he will be able to assist you.”

Suzuki took up residence in the Caruses’ large house, where he found, somewhat to his surprise, that his duties included helping around the house: “drawing water from the well, chopping firewood, carting in earth, going on errands to the grocery, and even cooking, if need be.” He received three dollars a week and room and board for his work, which, in addition to his domestic duties, soon included practically every job that needed doing in a small family publishing house. He learned to type and read proofs, and he edited and took photographs. His main duties remained in the field of translation: as soon as his first project, a translation of the Tao Te Ching with Carus, was finished, he translated Ashvaghosha’s The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana.

It was in LaSalle that he began work on Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism, the first book of his writings in English. Both Soyen Shaku and Carus had tried to present Buddhism to the West as a single ethical and scientific system. (Soyen would later tour the US with Suzuki to present this approach to Zen and ultimately published Zen for Americans, translated to English by his student.) But Suzuki directed attention to the organic, evolutionary nature of Buddhism. “Is there any religion,” he wrote in Outlines, “which has shown some sign of vitality and yet retained its primitive form intact and unmodified in every respect? Is not changeableness the most essential sign of vitality?” But it was not these ever-changing forms that constituted the kernel of the matter for Suzuki. “Mahayanism,” he wrote, “is not an object of historical curiosity. Its vitality and activity concern us in our daily life. It is a great spiritual organism; its moral and religious forces are still exercising an enormous power over millions of souls; and its further development is sure to be a very valuable contribution to the world-progress of religious consciousness.”

It was also in LaSalle that Suzuki came to see the direction that he would travel. “Innen [the workings of karma],” he wrote to Soyen, “are indeed beyond our thought. An idea that has no immediate effect, after being received by somebody, may later be of help to him in entering the Way of Enlightenment…all of a sudden flashing across his mind. The old Buddhist saying, ‘The merit of hearing the Buddha’s teaching even once is infinite, even if one falls short of believing it,’ refers to this truth…. It is my secret wish that if my thoughts are beneficial to the progress of humanity, good fruits will, without fail, grow from them in the future.”

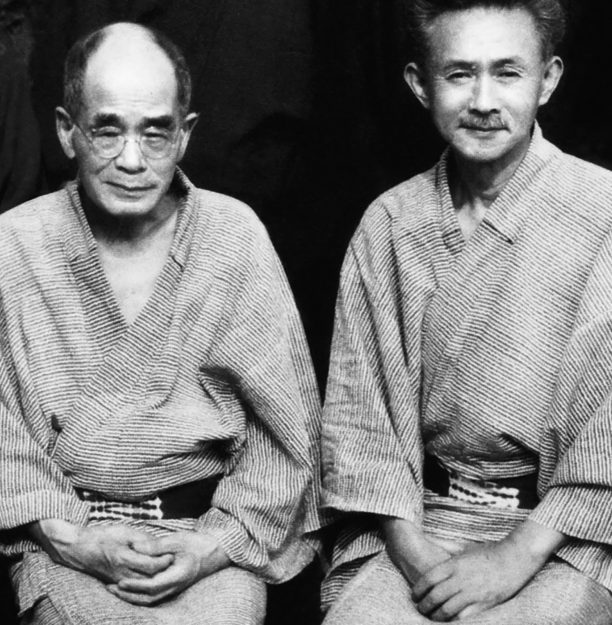

After a decade in the United States working with Carus, Suzuki returned to Japan, where in 1911 he married Beatrice Lane, a Radcliffe graduate (she had studied under William James) and a Theosophist. The couple lived in a small house in the compound of Engakuji until Soyen Shaku’s death in 1919 at the age of 59. They then moved to Kyoto, where Suzuki taught philosophy of religion at Otami University. There the Suzukis founded the “non-sectarian Mahayana” English-language journal The Eastern Buddhist. In 1927, Suzuki’s first series of Essays in Zen Buddhism, many of which had appeared in The Eastern Buddhist, was published in London.

The book secured Suzuki’s reputation in England, and in 1936, when he was 66, he visited the country to lecture at the World Congress of Faiths and at various universities, impressing many with his combination of playfulness and scholarship, but perhaps none more than a young Alan Watts, who described Suzuki in his autobiography as “about the most gentle and sophisticated person I have ever known, for he combined the most complex learning with utter simplicity.”

Suzuki spent the war years in scholarly seclusion in Japan after his wife and collaborator, Beatrice, died in 1939 (just a year after the publication of her own book on Mahayana Buddhism). Now he felt it was time to return to America for an extended visit, and in 1949 he left Japan.

After teaching for a year at Claremont Graduate School in Pasadena, Suzuki arrived in New York. He lectured frequently but had no regular academic appointment until Cornelius Crane, scion of a wealthy manufacturing family who had studied Zen in Japan, subsidized a series of seminars at Columbia. Suzuki’s students included psychoanalysts and therapists—Erich Fromm and Karen Horney among them—as well as artists, composers (John Cage was one), writers, and future Zen teachers like Philip Kapleau, then a businessman. It was at these seminars that the seeds of the so-called Zen “boom” of the late fifties were sown.

Teaching, for Suzuki, in addition to being a way of earning a living, was a means of thinking out loud about whatever books or translation he happened to be working on, and it was not uncommon for him to lose students completely as he crisscrossed the blackboard with a bewildering maze of diagrams and notes in Japanese, Sanskrit, Chinese, and Tibetan. The American Zen pioneer Mary Farkas remembered counting as many as a dozen people sleeping in their chairs one afternoon.

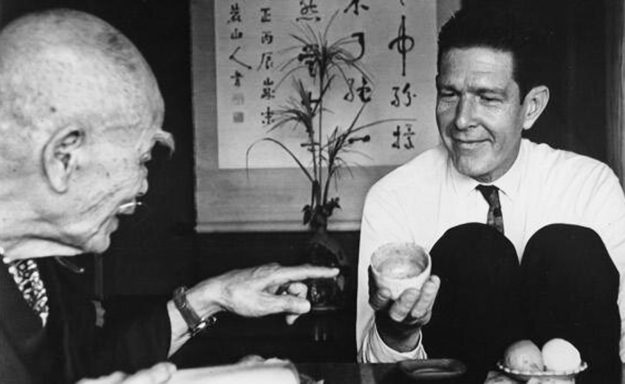

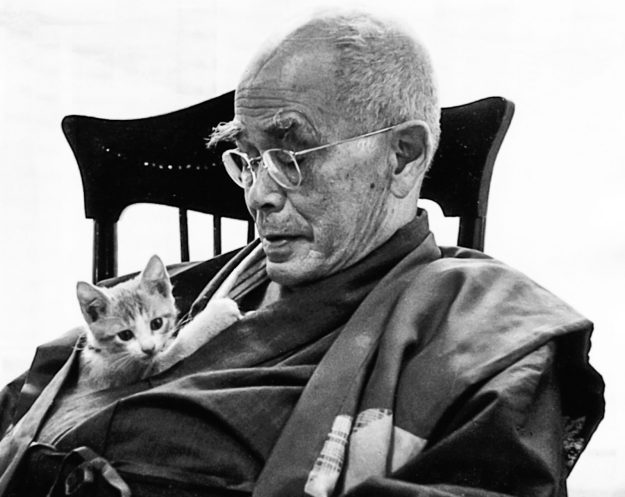

Without any effort or care on his part, Suzuki, by the 1950s well into his eighties, had become a public figure. He was interviewed on television, profiled in the New Yorker, even featured in Vogue. His age, wit, and air of gentle, bemused, scholarly abstraction caught the public imagination, but it was Suzuki’s character above all that impressed those who met him. Thomas Merton said of D. T. Suzuki: “In meeting him one seemed to meet that ‘True Man of No Title’ that Chuang-tzu and the Zen masters speak of.… In meeting Dr. Suzuki and drinking a cup of tea with him I felt I had met this one man. It was like finally arriving at one’s own home.”

Suzuki was also well known for his books, most of which were addressed to the layperson in a style at once rambling, humorous, and direct. It was as if one overheard him thinking to himself in his book-lined study late at night, digressing now and then to pursue a fascinatingly abstruse detail, or chuckling to himself as he translated an old Chinese Zen story. It was a unique voice, a lively mixture of authority and informality.

Suzuki had been careful to emphasize that Zen was Zen Buddhism. But at the same time, he refused to limit Zen to any time, place, or doctrine. “As I conceive it,” he wrote, “Zen is the ultimate fact of all philosophy. That final psychic fact that takes place when religious consciousness is heightened to extremity. Whether it comes to pass in Buddhists, in Christians, or in philosophers, is in the last analysis incidental to Zen.” It was this universalization of Zen that made it possible for all kinds of people to see Zen in all kinds of places.

Indeed, by the latter half of the fifties, the idea of Zen had become so popularized that it had achieved the status of a fad. In 1959, Suzuki’s student the writer and Zen teacher Ruth Fuller Sasaki observed that “Zen is invoked to substantiate the validity of the latest theories in psychology, psychotherapy, philosophy, semantics, mysticism, freethinking, and what-have-you. It is the magic password at smart cocktail parties and bohemian get-togethers alike.”

“His mind was always firmly rooted in that ‘fundamental something’ that makes life what it is.”

In 1957, the Conference of Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis, for which D. T. Suzuki was the featured speaker, brought together more than fifty analysts in Cuernavaca, Mexico. As early as 1934, Carl Jung had recognized that Zen and psychotherapy had a common concern, namely spiritual “healing” or “making whole,” and that the Zen master and psychoanalyst fulfilled a similar role in the individual’s search for wholeness. Suzuki himself had attempted to use Western psychological terms to explain Zen Buddhism, but he was critical of the limitations inherent in the analytic method of psychology.

While the lectures at Cuernavaca legitimized the ongoing dialogue between Zen and psychoanalysis, as usual it was Suzuki’s presence, even more than his words, that mattered most. Erich Fromm remembers that after the first two days of the conference “a change of mood began to be apparent. Everyone became more concentrated and quiet. At the end of the meeting…many had gone through a unique experience: they felt that an important event had happened in their lives, that they had waked up a little….”

D. T. Suzuki had come to exert an extraordinarily far-ranging influence in Asia and the West alike. He was read by Japanese priests and American beatniks; scientists, philosophers, psychologists, diplomats, meditators, artists, scholars, and students of religion sought his company and council. In 1958, for example, the day his book The Dharma Bums was published, Jack Kerouac, along with Allen Ginsberg and the poet Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s partner, visited Suzuki at the brownstone he shared with the family of his student-turned-caretaker, Mihoko Okamura.

“He had long eyebrows, as everyone knows, which put me in mind of the saying in the sutras that the Dharma, like a bush, is slow to take root but once it has taken root it grows huge and firm…,” Kerouac wrote in a reminiscence in 1960. “He sat behind a table and looked at us silently, nodding. I said in a loud voice (because he had told us he was a little deaf), ‘Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?’ He made no reply. He said, ‘You three young men sit here quietly and write haikus while I go make some green tea.’ He brought us the green tea in cracked old soup bowls…. When we left, I said, ‘I would like to spend the rest of my life with you.’ He held up his finger and said, ‘Sometime.’”

In a memorial issue of The Eastern Buddhist, the journal Suzuki had founded with his wife more than a half century earlier, Zenkei Shibayama, the chief abbot of the Nanzenji branch of Rinzai Zen, wrote of Suzuki: “His mind was always firmly rooted in that ‘fundamental something’ that makes life what it is—the origin of all existence, the very experience of Zen enlightenment. His studies in Zen, his studies of the Truth, were all directed toward this end. What Dr. Suzuki did was to live and ceaselessly strive to give expression to this ‘fundamental something,’ so that others may know of it, and to let it work for the benefit of all mankind.”

On July 12, 1966, after returning to Japan for the last time, and working at his desk to the very end, D. T. Suzuki passed away, at the age of 96. In a Tokyo hospital, he spoke his final words to those gathered at his bedside: “Thank you,” he said. “Don’t worry. Thank you, thank you.”

♦

Adapted from How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America by Rick Fields © 1981, 1986, 1992 by Rick Fields. Fortieth anniversary edition published in 2022. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc.