“There is a tradition in museums where it’s not clear whose voice is speaking. There is a voice telling you a story, and it’s [perceived as] the truth because it’s in a museum,” says art director Alexandra Grandjacques, who, along with art director Markus Strümpel, helped design Dharamsala’s new Tibet Museum. Built by the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), the de facto Tibetan government-in-exile, the museum opened in February 2022 and was a communal effort among experts from across the globe to let the voices of Tibetans speak directly as “I” and “we,” allowing only Tibetan voices—and those who support their human rights—to be heard.

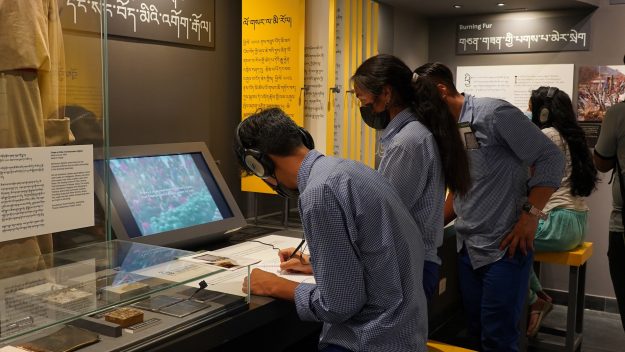

A permanent exhibit titled “I am Tibetan, This is my story” fills almost the entire museum space, and traveling exhibits will go to museums and galleries around the world. A smaller temporary exhibit space will showcase art by and about Tibetan people. The permanent exhibit is organized around ten core topics: Introduction to Tibetan culture, History, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Occupation, Resistance, Escape, Exile, Tibet Today, The Environment, and Being Tibetan. Visitors can contemplate moving images, hear the words of Tibetans, flip through books written by renowned Tibetan authors, view works of Tibetan fine artists, write messages to share with other visitors, listen to stories, hear traditional and modern Tibetan musicians, and touch objects to unveil key facts. With hundreds of pieces and several galleries to explore, a visitor can easily spend the entire afternoon taking in the exhibit, and the first panel sets a clear, affirmative tone about the purpose of the museum:

“We do not claim to be neutral. Our museum deliberately challenges China’s version of Tibet’s past and its distorted version of the present. With this museum we reclaim our right to tell our stories on our own terms and in our own words.”

In April 2000, the first Tibet Museum opened in Dharamsala’s Tsuglagkhang Complex, which houses the temple of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. As the museum slowly outgrew the 2,000-square-foot space, a vision began to take root among the museum leadership to establish a newly designed space within the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) complex, which includes several official buildings for the exiled government. The result is the 9,000-square-foot museum that opened this winter. Since the founding of the first museum, the collective photo archive has grown to include 40,000 photos related to Tibetan history and culture, many of which are displayed in the new space.

“Over the course of five years of building this new museum, we went door to door in India and contacted those who live abroad to ask Tibetans to donate their objects,” museum director Tenzin Topdhen told me. “And through these objects, we are trying to generate the true story of Tibet. If you go to other exhibits around the world, they aren’t necessarily representing the true voices of Tibet. We built this museum and told the stories from the grassroots level.”

In addition to Strümpel, Grandjacques, and exhibition curator Emma Martin, the project was headed by Tashi Phuntsok, who was the director of the Tibet Museum from April 2012 to April 2022. He was assisted by the museum team which included photo archivist Tenzin Ramjam, project officer Yeshi Wangmo, conservation and collection assistant Kunga Choedon, digital programme officer Tenzin Topdhen (who later became the museum’s director in April 2022), conservation and research assistant Tsering Norbu, photo archivist and conservation assistant Karma Tashi, and conservation and research assistant Tenzin Jinpa. Other notable contributors include conservation consultants Pankaj Sharma and Smita Singh, conservation assistant Nazima Choudhary, film curators Tenzing Sonam and Ritu Sarin, museum consultants Isadora Helfgott and Nicole M. Crawford from the University of Wyoming Art Museum, and Deborah Frieden from San Francisco. Core funders include the CTA, USAID, and the National Endowment for Democracy.

Topdhen emphasized that in an exiled society, institutional memory can be unreliable and eventually lost, which makes the donated historical objects, such as dzi, or Tibetan prayer beads, important for documentation and to preserve collective memory. In this way, he said, the museum also serves as a national archive, safeguarding cultural memory, in Tibetans’ own words and artifacts.

In contrast, the Tibet Museum in Lhasa, built entirely by the Chinese government, is housed in a facility that extends over five acres (23,000 square meters), but includes no independent voices of Tibetans or perspectives, Topdhen pointed out.

A panel in the gallery that covers Tibetan culture reads, “In Tibet our culture is threatened by Chinese policies that aim to erase it.” Monasteries have been reduced to tourist attractions, teachers are jailed for teaching the Tibetan language, and the civilization of Tibet is presented as a relic of the past. In keeping their culture alive, Tibetans engage in Lhakar, a non-violent protest movement. Another panel refers to a “Museum of Absence,” which explains that when people flee through exile, they carry very few belongings. The message continues with an invitation for Tibetans to donate their objects to the museum for preservation.

The new Tibet Museum isn’t just unique in the voice it gives Tibetans. “In contrast to the [original Tibet Museum], which just featured photos and text, we wanted this one to be primarily interactive,” said Strümpel, who has been volunteering his services as a designer for both the old and new museum since 1999.

“When you enter the museum, it’s at first dark—dim lighting and no windows—so the visitor can concentrate on the illuminated Buddhas, then slowly the space becomes brighter, also with the use of lighter colors. Then, when you move into [the “Exile” exhibit], there’s a window that faces the Parliament in the Exile building, which creates a dialogue between the museum content and the official building.”

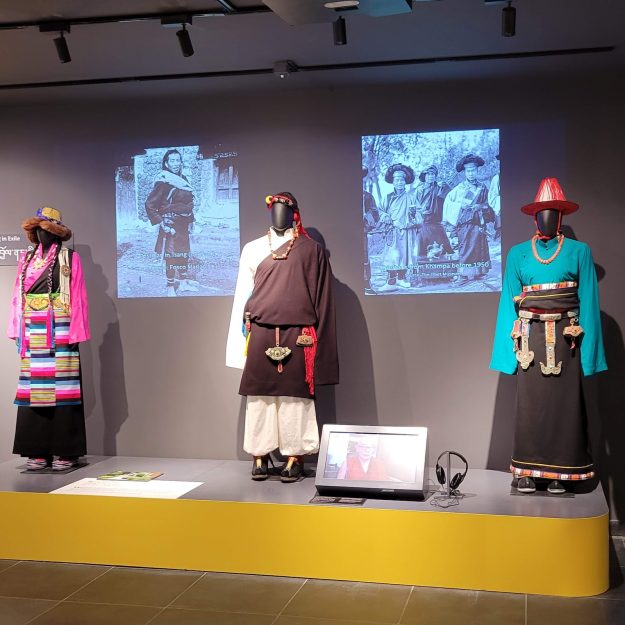

As a people’s museum, many of the displays portray the daily life of Tibetans, including monks. In the Tibetan Culture gallery mannequins showcase traditional Tibetan clothing, including distinct styles from each of the three major regions: U-Tsang, Amdo, and Kham. These include the signature chuba, a robe-like tunic worn by both men and women. In one video, the Dalai Lama’s tailor speaks about his role in transitioning His Holiness from brocades and wool to cotton after he left the frigid climate of Tibet for subtropical India. The tailor designed new versions of the monk’s robes, or Tenzin Ngolen, first for the Dalai Lama, which once approved, became the style for all monks and nuns. Further into this gallery, visitors learn about the Tibetan staple food called tsampa, which is made from barley flour into porridge or dumplings. The importance of this traditional meal is highlighted in a video with the Dalai Lama, along with examples of utensils and earthen cookware.

Across from the garments is an illustrated map and topographic model of Tibet that highlights locations on a projector screen, along with a poetic description, from 8th-11th-century Dunhuang manuscripts:

Our lands, the center of heaven / The core of the earth / This heart of the World / Fenced round by snow mountains /The headland of all rivers / Where the peaks are high and the land is pure / A country so good / Where men are born are sages and heroes and act according to good laws / A land of horses ever more speedy.

In the gallery titled “Who Writes Tibet’s History?” Tibet’s independence as a nation is illustrated through a detailed timeline of the country’s history. Next, visitors arrive at the “Occupation” gallery to learn about the Chinese government’s oppression that hangs over the past and present of every Tibetan, from the 1950s invasion to the ongoing, systematic destruction of their land; the torture and deaths of millions of people; and the continued process of exile. Here the stages of the Chinese invasion are featured, beginning in 1949, and moving through key markers, including the Seventeen-Point Agreement, Democratic Reform, and the Cultural Revolution.

In the “Resistance” gallery, a video of Christa Meindersma, a woman who was shot and severely injured by Chinese soldiers during a peaceful protest in 1988, offers firsthand testimonial of one of the resistance efforts. Other testimonials address the 1959 uprising, Mustang resistance, Nyemo revolt, and the uprisings between 1987 to 2008. An installation called “Burning Fur” covers self-immolations and features a harrowing video alongside a box filled with the last statements made by 153 protesters since 2009.

In the gallery titled “Escape,” more testimonies, film, donated objects, and photographs portray the circumstances of departure and the dangerous journey into exile, including a moving short film that follows a father and young daughter who risk their lives walking in subzero temperatures across glaciers and perilous terrain. In another video, we meet Nyima Lhamo, niece of Tenzin Delek Rinpoche, a highly respected spiritual leader who died under suspicious circumstances in 2015 in a Chinese prison while serving a life sentence as a political prisoner. Lhamo describes her escape from Tibet in 2016, which is shown alongside a display of three belongings she carried on the perilous journey to Nepal. The “Archive of Escape” invites visitors to write their own memories of escape, reiterating that exile continues in the present for so many.

On the other side of this gallery, a nondescript room the size of a closet and entirely painted white screens a continuous loop of a short video, which comes with a warning of graphic content. The panel outside the room introduces the video, also with a warning. It captures the tragedy of Kelsang Namtso, a 17-year–old nun as she is shot by Chinese border patrol, as she was crossing the Nangpa La Pass, a route of escape from Tibet to Nepal, en route to exile in India. Others were injured in this incident, and many other Tibetans continue to face death, injury, and tremendous threats from the Chinese military as they attempt to escape. The enclosed space serves as a private, quiet space to mourn Namtso.

When I asked Martin, the museum’s curator, about the team’s approach to presenting challenging and sensitive content, she replied by email that, “It was important to show Tibetans not as victims but as individuals who made unimaginable choices when placed under extreme pressure. These choices were about their lives, their families, their communities, their culture and religion, their personal belongings, their country and their futures.”

Martin noted as the team planned the exhibit, statistics on the atrocities or exile were not as important as listening to firsthand experiences.

“We didn’t want visitors to only acknowledge the numbers of Tibetan displaced or killed that are so often quoted, but we wanted visitors to see and acknowledge the humanity of someone who had made the decision to become a refugee, to fight, or to protect their community and religion. We wanted visitors to understand that each person listed as a number had a personal story to tell and a life that is valued and of value. It is about feeling the weight of that loss by hearing from those affected, rather than simply reading statistics,” she said.

Moving from stories of escape, there’s an energy of hope in the gallery titled “Exile.” Images and testimonies express how Tibetans reestablished cultural institutions across India through the government in exile, and around the world. And critical for anyone interested in the details of human rights violations is the “Tibet Today” gallery, which lays out the devastating impact of China’s policies. Showcasing the important work of human rights groups and investigative journalism, the materials here also cover the extent of repression Tibetans face under constant military and technological surveillance.

Meanwhile, the “Environment” gallery exhibit emphasizes the critical role the country plays in providing fresh water (as the “Third Pole”) to almost one fifth of the world’s population, and the devastating impact of China’s large-scale deforestation, mining, and dam projects.

“Many of the events you see in the museum aren’t just from the past; they are continuing now,” said Strümpel, who said that he feels his contribution is one way he can support Tibetans.

“The motivation and the future vision of the museum is that we continue telling this story. It’s not ending; it’s still happening,” he continued. “We want to continue with the traveling exhibits to teach others. Our work is not finished.”