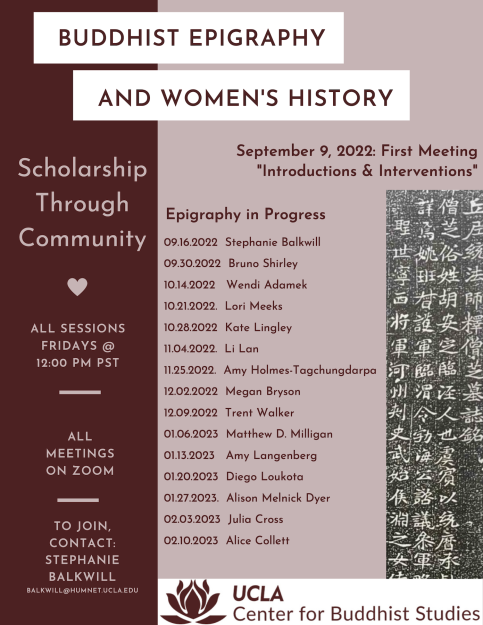

A group of Buddhist scholars with interests in epigraphy—the study and interpretation of ancient inscriptions—are meeting weekly for an informal series of talks titled “Buddhist Epigraphy and Women’s History.” The sessions began in September and are held over Zoom nearly every Friday from 3 p.m. to 4 p.m Eastern, with the final session scheduled for February of 2023. Each week, one of 15 scholars shares an aspect of their epigraphical research as it relates to women’s history.

The series was organized by Stephanie Balkwill, assistant professor of Chinese Buddhism at UCLA, who sought to combine her two loves of community-building and women’s history. “Reading epigraphy is difficult, so it’s best done in community. We all bring different skills to the table,” Balkwill said. “I wanted to form a group that could foreground community in Buddhist studies while also making these difficult sources more accessible.”

The 15 Buddhist scholars range from professors at research universities to graduate students, whose areas of expertise include East, Central, South, and Southeast Asia. Each “epigraphy in progress” session is designed to be short and fun, and participants are encouraged to bring material that has mystified, fascinated, or even stumped them.

During the introductory session on September 9, Wendi Adamek, religious studies professor and Numata Chair in Buddhist Studies at the University of Calgary, discussed her process of interpreting epigraphy and the role of imagination in historical scholarship. On October 28, Kate Lingley, associate professor of art history at the University of Hawaii, will share her research on the networks and relationships of non-elite women in medieval China. Other scholars include Alice Collett, Amy Langenberg, and Trent Walker.

According to Balkwill, sources like epigraphy and art history can enrich the historical record by filling in the gaps left by Buddhist texts, which have been edited, redacted, and handed down by a tradition of elite monastic men. “A lot of what’s left out of texts deals with the religious practice of women, cultural outsiders, or people who did not hold power in any given place where these texts were transmitted,” Balkwill said.

Balkwill first dove into epigraphy as part of her research on women living in 4th- and 6th-century northern China and how they interacted with Buddhism. Since texts on women’s lives during that time are scarce, Balkwill’s project supervisor advised her to look into the period’s rich epigraphical record. By studying various inscriptions written on or placed inside stupas and tombs, Balkwill was able to glean rare insights into the lives of women in the period. “I’ve been really invested in trying to surface voices and practices that have been lost,” she said. “We can’t recover those things from Buddhist texts. But we can if we look at sources like art history and epigraphy, which are just as valid and offer an inclusive vision for the practice of Buddhism today.”

The “Buddhist Epigraphy and Women’s History” series is open to anyone who wants to join, regardless of their expertise. Interested participants can contact Balkwill for the Zoom information at balkwill@humnet.ucla.edu.

♦