“WHAT DO YOU THINK OF when you hear icon?” I ask at the dinner table a few days before my fifteen-year-old daughter and I visit Frederick Franck, a ninety-six-year-old Dutch-born artist who is the author ofThe Zen of Seeing and about thirty other books.

“I think of Carl Icahn, the corporate raider,” says my husband, Jeff.

“I think of a computer icon,” says Alexandra.

“Nobody thinks of a religious icon,” I comment.

“Do you mean like the Dalai Lama?” asks Alex.

“A celebrity or someone who embodies particular qualities can be a kind of icon,” I say.

“Carl Icahn could be considered a celebrity icon,” says my husband.

“Plus, I have pictures of celebrities on my website, so technically they can also be computer icons,” adds Alex.

We establish that the meaning of icon has stretched pretty thin since the sixth century, when Eastern Orthodox Christians painted Mary and Jesus as objects of veneration. In the car on the way to the four-acre property that Franck calls Pacem in Terris (Peace on Earth) in Warwick, New York, I explain to Alex that the sculptures we are going to see were not created according to strict rules, the way traditional icons were. According to Franck, the images he cut in black steel or carved in wood or stone came to him spontaneously and were executed very simply and directly, very Zen.

Alex asks me why I think it’s so important for her to go see them in person. She assures me she could find pictures of Franck’s work on the Internet in about two seconds.

I tell her there are some impressions that can’t be had on a flat screen. She asks me what the big deal is about reality anyway.

I am driving Alex to meet Franck and see his icons because I believe the world that she—that we—inhabit for hours every day is flat. As foreign affairs columnist Thomas L. Friedman regularly conveys in the New York Times, digital communications have melted hierarchies and borders and made distances disappear. Every day, Alex communicates with kids (we are pretty sure they’re kids) from all over the country and all over the world.

“I don’t feel victimized by the media or the Internet,” she tells me. “I think of it as a friend. I take what I want and leave the rest.”

This she does. The Internet is a river, and everyday she goes trolling for new images, information, entertainment. What it can’t give her is the experience of having an image or an insight come like a flash of lightening in the night, welling up from the depths of our own being in response to our deepest questions.

The work we are going to see—images of the Buddha, the Christ, and other renderings of what Franck designates as the “True Human” or the “True Self”—are distillations of Franck’s deepest experience. He has written that these sculptures are icons because they point toward a reality that can’t be verbalized, only felt directly, in the depths of the heart. As complex and profound as much of the work is, it also has a bare quality, as if shorn of all artistic ambitions and attachments. The icons are very personal.

I hope they touch Alex the way they touched me. I want her to have a glimpse of what Zen Buddhists call our “Original Face.” I want her to know what it looks like to dare to be simple, aware of the world but not consumed by it. I want her to know that what is merely personal can open into the vastness of true human nature.

Alex tells me she isn’t into the art scene. Good, I tell her. Neither is Franck. He had many critically acclaimed exhibitions in leading galleries in New York and Europe until he grew fed up with what he perceived to be the self-centeredness and nihilism, the mindless drive to be new. He decided that being liked by the critics or bought by Mrs. So-and-So wasn’t what art was about. “I decided I had to start all over again,” he had told me when I’d met him the year before. “I went to look at the bulls painted on the walls of Lascaux thirty thousand years ago. I was there in the ’50s, when you could still go in the caves. I wanted to draw as these people had drawn on the rock walls. So I drew and drew and drew. I had no pretensions, I just had to do it.”

The Lascaux paintings had the original quality he was looking for. “There has been an exaggerated use of the word original in our culture,” Franck said. “I use it in the sense of being in direct contact with our origins.”

I am taking Alex to see Franck’s work because at fifteen years old she is already a seasoned and discerning consumer, and I want her to know that some art exists that was not created to be consumed as a kind of decor or form of novelty entertainment. I want her to meet Franck because while it is popular in Buddhist circles to maintain that we are “human beings, not human doings,” Franck’s life and work is a reminder that discovering who we really are in the midst of life actually does require some action. We have to dare to question what we see. We have to be willing to open our eyes and our hearts.

Franck started asking serious questions about what it means to be human at an early age. He was born in the Dutch town of Maastricht on the Dutch-Belgian border, and when he was five years old he watched the Kaiser’s armies roll into Belgium. From his attic window he watched a neighboring town burn and people fleeing, carrying what possessions they could. He remembers standing at an attic window, eating a bunch of grapes. An old man who was struggling by with a birdcage happened to look up at him and Franck threw the grapes down “in a gesture of desperate compassion.”

“I don’t believe in gurus,” Franck told me on my first visit. “I believe that each one of us has a riddle to solve, the riddle of what it means to be human. When we are born we are some kind of hominid, a little anthropoid animal with the potential and the capacity to become human.”

What manifesting true humanity looks like and feels like—being honest, transparent, spontaneous, and especially compassionate—became the subject of his life and art.

These days, pursuing individuality has come to seem negative or retrograde in Buddhist circles. It is associated with selfishness and superficiality, with clinging to a notion of the goodness or rightness of what separates us from other beings. But Franck’s life and work shows that becoming a true individual doesn’t necessarily mean cherishing what we believe to be our talents, our style, our precious, inviolate inner selves. It can mean casting off ties to fame and fortune—and even an attachment to Buddhism. It can mean leaving the shallows of our experience for the depths.

WHEN HE PUBLISHED The Zen of Seeing in 1973, Frederick Franck became a celebrity Buddhist icon to hundreds of thousands of fledgling Baby Boomer Buddhists and artists. His aim, however, was not to write a book about Zen Buddhism or to establish a new career as a Zen Buddhist artist, but to explore what it means to see the world from the inside instead of merely looking at it. “Suddenly I am all eyes,” he writes. “I forget this Me, am liberated from it and dive into the reality of what confronts me, become part of it, participate in it.”

Handwritten and filled with lyrical line drawings that capture the exquisitely ephemeral details of faces and places, The Zen of Seeing reveals how the particular can coexist with the universal. All the work that followed was to have a similar preoccupation. “In every face the Face of Faces is indeed discernible,” writes Franck in Ode to the Human Face, a pocket-sized book of photographs and essays published in 2004, when he was ninety-five years old. Frederick Franck waits for Alex and me in the cocoa-brown house that he and his wife, Claske, bought on impulse nearly a half century ago on their return from a trip to Africa. They had spent the previous three years working in the clinic run by the great humanitarian Albert Schweitzer, whose philosophy of “reverence for life” resonated deeply for Franck. An artist to the core, Franck had nonetheless gone to medical school to please his mother. He switched to dentistry so he would have more time to paint. Then the artist learned that Schweitzer needed an oral surgeon.

In Africa, Franck drained abscesses and performed operations on patients who arrived at the clinic by dugout canoe, while Claske served as a nurse. Through it all, he drew and wrote about his adventures, producing My Days With Albert Schweitzer and African Sketchbook, which featured an introduction by Graham Greene.

On their return the couple took a weekend drive away from the city and came upon the gaunt ruin of a house on the banks of the Wawayanda River. It had once been McCann’s Hotel and Saloon, built around 1840. They loved the way the house nestled into the landscape. They thought it embodied a kind of beauty that was primeval and earthy, rooted, inward. They thought it had wabi-sabi: “Our taste seemed closely related for some reason to two basic aspects of classical Japanese esthetics: wabi and sabi,” Franck writes inPacem in Terris: A Love Story. “Wabi stands for an utter simplicity, a voluntary poverty of means, a chaste absence of any sign of conspicuous consumption. . . . Sabi refers to the charm of the agedness of things: a beloved old chair, a Victorian ceramic bowl, broken long ago, not discarded but respectfully glued together.” A contractor who happened to be descended from a long line of Dutch windmill makers lived nearby. He helped them pull the building straight.

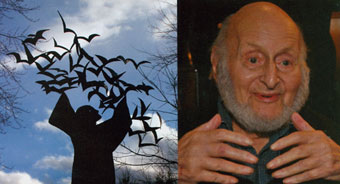

We find Franck sitting in a wheelchair in the living room that was once the taproom, Claske by his side. At ninety-six, almost completely deaf and nearly blind, Franck is still luminous. That glow, the fringe of white beard, and his Dutch accent combine to give him the look of someone out of time, human wabi-sabi. His son, Lukas, brings out a tray of espresso. Caske closes the old artist’s stiff hands around the tiny espresso cup.

Alex declines a cup with a small sweet smile and a shake of her head. She looks around the dim room, at large paintings on easels. There is a shard of glass on a stand painted with the same tranquil ideogram of a face that adorns his Buddhas. He tells us he calls it the “Unkillable Human” and that it was inspired by the horror of September 11.

“I wish I could see your face,” Franck tells Alex. “Now all I can see are shadows.”

In his book Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers, the design philosopher Leonard Koren describes the Japanese aesthetic as the opposite of our society’s “headlong rush into sameness,” our drive for perfection, slickness, mass-produced and mass-marketed fabulousness. Sitting with Franck in these surroundings, it becomes clear that gestures and lives can have wabi-sabi, a beauty and intimacy that shines through the wear and brokenness that comes with age. Although it is difficult to pin down in words what it means to be a True Human or have an Original Face, it has to do with accepting impermanence and with living from the heart without any hint of pretension or falsity. “Pacem in Terris is totally free, in every sense,” Franck tells us. “We get a constant stream of people, especially in times of great worry like these or if they have suffered a great personal loss. They just come here and sit and pray. We don’t talk to them. They don’t get any message. They get what I call an ‘oasis of sanity,’ of inwardness.”

I ask him if he can sum up what it means to be human rather than a mere hominid.

“I have had very great luck to have been faced with three people in whom I felt that human capacity. They were Albert Schweitzer, D. T. Suzuki, who was actually the man who introduced the Zen spirit to Western civilization, and Pope John XXIII.”

Franck describes going to see Suzuki at Columbia University: Franck asked him what Zen is, and Suzuki told him, “Zen is what makes you ask the question.”

“When you ask, ‘What is Zen?’ you are asking, ‘Who am I?’ And when you ask ‘Who am I?’ you are asking, ‘What is it to be human?’” Franck remembers Suzuki telling him. “It is the existential question, the primal riddle we bring along into the world when we are born and must answer before we leave it, on penalty of having gone through life in vain.

“I visited Suzuki’s grave in Kamakura, Japan,” says Franck. “I never visit graves, not even my own parents’. But there I made a deep bow. I think he touched the very principle and core of humanness.”

“Zen is not a religion,” Suzuki told Franck. “It is the profoundly religious ingredient in the world religions.” It is in this spirit that Franck playfully declares that Angelo Roncalli, better known as Pope John XXIII, was not only the greatest human being he ever met but also a great Buddhist.

“I don’t really think of him as Buddhist any more than I call myself Buddhist,” Franck qualifies when pressed. “I think of the Buddha figure and the Christ figure as the greatest incarnation of the human, and I experienced this presence in Pope John XXIII, as I did in Suzuki, who was a Buddhist by profession, you could say.

“On October 12, 1962,” he continues, “I was walking up Fifth Avenue in New York on my way to a meeting at Macmillan Publishers. I happened to see the Times, and there was a picture of John XXIII and the words of his opening speech to Vatican II. I turned on my heel and went home. I said to Claske, ‘We’re off to Rome at once. Even if I go bankrupt, I have to go there. I want to draw that man and what he’s doing.’”

The couple did go. He made friends with a lieutenant in the gendarme who allowed him to sketch in St. Peter’s, and ultimately he made hundreds of drawings of the pope and the Vatican II proceedings that Franck believed infused the Church with the gospels.

In The Zen of Seeing, Franck describes the pope’s face as “human in all its greatness, without a trace of falsity or pretense. . . . He was a fat man, not handsome, but beautiful, for he was a genius of the heart—maskless.”

FRANCK SHOOS US outside to see the icons.

We wander among about seventy icons placed along the riverbank and in a sculpture garden across the road. Here by the river is the Buddha holding up a flower. There are many versions of the Buddha and also of the risen Christ, of the “True Human” and “The Unkillable Human.” We come upon a steel eye icon inscribed with a saying from Hui Neng, the sixth-century Zen patriarch: “The meaning of life is to see.” All the works in the garden ask us to realize that being human means living as if there is no separation between seeing and being seen.

In his work and in his life, Franck practices a kind of cosmic cosmopolitanism. He calls himself “trans-religious”—“an unaffiliated Buddhist” and “an unaffiliated Catholic.” Born into an agnostic family in a Catholic town, he grew up experiencing the church in a personal aesthetic way. It was “a dream consisting of candlelight, Gregorian chants, Mary, great art.”

When he encountered the Buddhist tradition as a young man he let that also be as rich as it is, all the while seeking to cut through to what he felt was universal. To Franck, the Buddha, like the Christ, was a True Human.

“Buddha Nature, Spirit of Christ, strike me as beyond all theological conceptualization,” he has written. “They are radically experiential.”

As the sun sets, Alex and I stand before the “Kwannon Madonna.” Here Franck captures the spirit of Kwan Yin, of Mary. She has a softly smiling Buddha face and a body fashioned from a hollowed tree trunk. She is filled with wooden figures of human beings in different shapes and sizes, all manner of expressions carved into their faces. This is what it means to love like a mother loves a child, I register. You don’t so much make a decision to love them as open up and take them in.

Here Alex can feel the all-embracing love and compassion Kwan Yin represents. It is radically experiential.

By the time we make it back to the house, it has grown dark. Franck sits waiting for us in a pool of light. He is eager to hear our impressions, lamenting that now he can no longer be out there himself. I ask him what is really important in the end.

“Awakening the heart,” he answers. “Without a doubt.”

In his art and in his life, Franck teaches that embracing our true individuality—embracing our own deepest experience, learning to see and relish the universal in the particulars of our life—is the way to find our true humanity.

In his books and in conversation, Franck speaks of figures of great attainment, Dogen, Meister Eckhart, in the same breath as great artists, Bach, Beethoven, Rilke, Basho, Rembrandt. He believes that what we find “great” in art is the True Human letting their true humanity shine through. “Every time I listen to Bach it becomes clear to me it’s almost unbearable in its profundity and intimacy and variation and strength and severity and tenderness.”

I ask Franck if Bach’s music might not point to what it means to be a true human being. There is nothing fixed or solid. There is an open quality, a sense of this exquisitely unique event unfolding according to a law that applies to us all.

“I understand what you mean,” says Franck. “It’s that way with Rembrandt, too. There is this quality of recollection.”

The Sanskrit word smriti, often translated in Buddhist contexts as “mindfulness” or “awareness,” literally means “what has been remembered.” Great artwork, including Franck’s, leads people to a state of smriti, of mindful awareness. What is reclaimed or re-collected is a sense of what it means to be human.

In the end, Franck maintains, all of his art is about resurrection—it is about the reality of suffering and our capacity to find something greater than suffering.

THE JEWEL OF PACEM IN TERRIS is the stone sanctuary across the river from the house. Also namedPacem in Terris, the sanctuary was converted from the ruin of an eighteenth-century watermill. Franck took the name Pacem in Terris from the last Encyclical (or public teaching) of Pope John XXIII, written while he was dying. “God,” wrote the former Italian peasant, “has imprinted on man’s heart a Law his conscience enjoins him to obey.”

Franck took this Law to be the one Dharma, the one Truth. After Pope John XXIII died, Franck set to work, eager to create a refuge dedicated to the awakening of the heart. The roof is meant to look like the wings of a dove. On the steps descending into the sanctuary, however, one is met by a “nail tree,” a wooden column bristling with nails representing the uncounted hundreds of thousands of humans who have been slaughtered in Franck’s lifetime.

The inside of the sanctuary smells like earth and stone and water. In the dim light, we make out a sculpture of Pope John XXIII, massive and serene as a tree trunk. The figure confronts a carving of the angel of destruction, which hangs suspended from the ceiling. There are tiers of seats leading up to an icon of a rough human, a potential human. In the floor there is a pool of water where the mill wheel used to grind.

“Just so you know, I could live in a place made of rough stone like this,” Alex tells me.

Alex and I agree that we like the earthy, intimate, cavelike atmosphere. It seems like a good place to listen to a Bach concert or to just sit in the quiet. Alex wonders what life must have been like before technology. She thinks she would feel so much smaller.

Before we leave the sanctuary, Alex and I sit on the wooden deck that surrounds the mill. There, outlined against the rushing Wawayanda River, is an icon of a hand weeping blood and tears, listing all the places on earth where people have perpetrated crimes against humanity, including this country.

“Just so you know, I agree with that,” Alex says. “I could also live near water like this.”

Not killing also means not killing our humanity in the midst of life, I reflect. It means not killing our full capacity for experience. Alex adds that she wouldn’t want to live without technology all the time. I tell her to be herself.

We go back to the house and say goodbye. Before we leave, Claske asks us to be sure and leave our email address. Alex and I look at each other and smile.

Contributing editor Tracy Cochran’s last piece for Tricycle was her interview with Mu Soeng, “Dharma for Sale,” in the Winter 2005 issue.