I found myself returning to several of the articles in the recent Winter 2022 issue of Tricycle. The Buddhist concept of anatta, no-self, was discussed directly by Andrew Olendzki in his essay of the same title. Olendzki writes:

[No-self] goes beyond simply denying that a self exists. At the heart of the matter is how to regard the very word “exists.” According to Buddhism, phenomenological events do occur, but ontological entities do not underlie them. The functions associated with a self, such as thoughts and emotions, “exist” in the sense that they happen, but it is a projection of our language and imagination to say further that a solid entity, a spiritual essence, an unchanging substance or a transcendent energy therefore “exists” as something beyond these occurrences.

A stable substrate for our experience, a self, is “a projection of our language and imagination,” and nothing more.

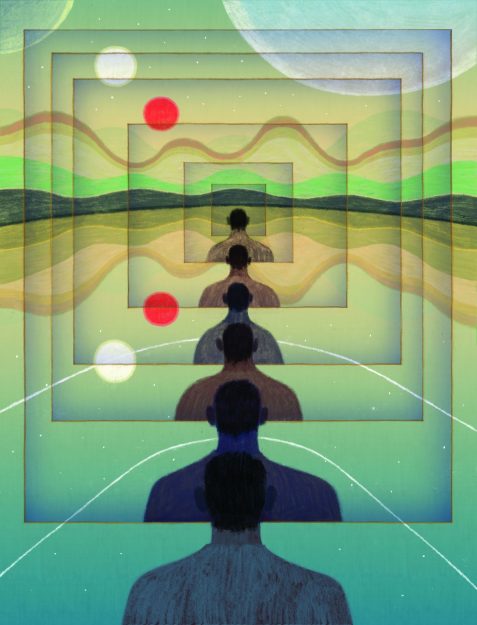

In a similar fashion, Pema Chödrön ponders what passes through the transitions from lifetime to lifetime in her essay “What Goes through the Bardos?”:

We can’t locate or describe any stable element that lives through all our experiences…. There are just individual moments, happening one after another. What we think of as “consciousness” is fluid, more like a verb than a noun.

Our consciousness, our “self,” is not some entity that could be distinguished apart from the flow of our experience.

This deconstruction of the self seems to be contradicted by Yoshin David Radin’s essay “Left Foot, Right Foot.” In that essay, Radin writes:

There is something constant through all these years, and that is the light that is illuminating you. Once you enter the spiritual path, your life is no longer about fulfilling your individuality, that is an impossible thing….

There is within you that which is beyond birth and death, beyond success and failure. It just knows that you are, and it is…. [Y]ou should realize that within you is that which is eternal, which is unaffected, which is present within all things as the core of their being, and which is pure spirit, completely nonmaterial.

How do you become aware of the inner illumination? How do you become aware that there is a deeper knower? The path will always be in the present moment.

It seems there is something “constant,” “eternal,” “pure spirit” that is “completely nonmaterial.” What is someone struggling with the Buddhist concept of anatta to do with this? Is there a self or isn’t there? Is it, as Yoshin David Radin’s article seems to suggest, that we discard a “false” self to discover a “true” self?

What is someone struggling with the Buddhist concept of anatta to do with this? Is there a self or isn’t there?

While looking around for comments by other Buddhist teachers on this subject, I found, in the Spring 2014 issue, the short article “There Is No Self,” by Thanissaro Bhikkhu. He writes:

“There is no self” is the granddaddy of fake Buddhist quotes. It has survived so long because of its superficial resemblance to the teaching on anatta, or not-self, which was one of the Buddha’s tools for putting an end to clinging. Even though he neither affirmed nor denied the existence of a self, he did talk of the process by which the mind creates many senses of self—what he called “I-making” and “my-making”—as it pursues its desires.

In other words, he focused on the karma of selfing. Because clinging lies at the heart of suffering, and because there’s clinging in each sense of self, he advised using the perception of not-self as a strategy to dismantle that clinging. Whenever you see yourself identifying with anything stressful and inconstant, you remind yourself that it’s not-self: not worth clinging to, not worth calling your self. This helps you let go of it. When you do this thoroughly enough, it can lead to awakening.

As Leigh Brasington told Wendy Biddlecombe Agsar in their article “The Richest Vein in All of Buddhism”: “the Buddha wasn’t doing metaphysics; he was a phenomenologist.”

So where does this leave someone stuck at the contrasting comments by Andrew Olendzki, Pema Chödrön, and Yoshin David Radin? If we accept that all discussion is phenomenological and not metaphysical, I guess we’re fine. But has all discussion been only phenomenological? It certainly appears that Olendzki, Chödrön, and Radin are making metaphysical claims. Olendzki says no “ontological” entity underlies our thoughts and emotions. Pema Chödrön suggests there is no “stable element” throughout all of our experiences. David Radin, in contrast, says there is something “constant” through our years on the spiritual path. Have these three teachers gone beyond the foundational phenomenological claims of the Buddha to practice metaphysics?

I asked one of my teachers, Jon Yaffe, about this. His usual insightful comment was that this was why he preferred using “not-self” instead of “no-self.” He also remarked that he didn’t see phenomenology and metaphysics as dualistically opposed endeavors of the mind. I liked that, but it’s so easy to get confused, to skip past meditation’s invitation to see the dukkha caused by the mind’s activity of “selfing” and think that what’s happening instead is a debate about the ultimate structure of reality.

—Brian Wohlin

I am grateful for your commentary and coverage of the assisted dying topic, including Sarah Fleming’s review of This Is Assisted Dying by Dr. Stephanie Green (“The End of Suffering,” Fall 2022).

From any perspective, Buddhist or otherwise, this is a compelling, complex and conflicted discussion.

An important omission in your articles, however, is the 2021 change in Canadian legislation that permits death to be facilitated without the previous qualification that death be “reasonably foreseeable.” Regardless, many people still simply default to a person’s choice in this matter, preferring to uphold the principle of autonomy over all else in making the decision to end a life. Herein lies a highly contested political and ethical topic.

How is “choice” to be considered if, in the absence of adequate income, housing, mental health services, and pain relief amid government spending cuts, we offer instead a quick and cheap death? What is the Buddhist perspective on the thorny questions emerging out of the politics of death facilitation, or “deliveries,” as Dr. Green prefers to use in describing her work? And what is “choice” anyway, if not laden with context and more?

The challenges to the new Canadian legislation are not theoretical. The case of Toronto resident Michel Fraser is illustrative in the extreme, i.e., doctor-facilitated death when it is not reasonably foreseeable.

I think there is much more to be said on the Buddhist ethics of assisted dying. Tricycle’s segue into the topic is a good start.

Respectfully,

Douglas J. Cartan

I’ve been reading Tricycle since the early nineties, almost since it began, and I thought “The Invention of Nothing” (Winter 2022) by C. W. Huntington Jr. (1949–2020) was the most brilliant article I’ve ever seen in the magazine. I immediately searched the archives for other things he had written and bought his latest book. Thank you so much for printing it.

—David Guy

♦

To be considered for the next issue’s Letters to the Editor, send comments to editorial@tricycle.org, post a comment on tricycle.org, or visit us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.