WHY BE a Buddhist? After seventeen years of practice, I still sometimes think I need my head examined. How did my Burmese teacher convince me, for four whole years starting in 1984, that I was going to hell? How many bows have I made to old, brown men on thrones? What about the little boys the men once were? I’ve bowed to them, too, tiny kids taken from their families at an early age, forced to wear huge crowns, bless multitudes, and sit weeping through rituals that even adults find tedious.

What am I doing in a religion whose formal expression is a highly defended, medieval, male, sexist hierarchy?

I can hardly discuss these thoughts with anyone. My secular-humanist friends pity me; the Buddhists tell me to go and meditate until I feel better. Buddhist logic says that if I’m mad and sad because I’m a woman, I’m also a woman because I’m mad and sad. It’s karma. If I keep indulging negative thoughts, I’ll be reborn as a woman again—or worse, since the lowest hell is reserved for those who criticize the Buddhist teachings.

Personally, I’d be more than happy to stop fixating on the differences between women and men. This would be easier if our beloved tradition stopped doing it, too. But it’s hard to stop behavior that one won’t acknowledge. Even His Holiness the Dalai Lama, a most compassionate human being and nuns’ advocate, said, after hearing Western women talk about sexism in the Buddhist tradition, “Some of these problems may be more imagined than real.”

The historical Buddha abandoned his wife, and named his infant “Fetter”: is this a model for how a spiritually motivated person should behave? Must I believe Pali texts’ insistence that a fully enlightened Buddha must have “a penis with a sheath”? At Wat Suan Mokkh, in Thailand, there’s a painting of a sexy lady, her miniskirt adorned with scary barbed hooks as she slyly displays a fishing rod: she’s a warning of dangerous female intentions. Is it rude to suggest lust be cleansed from monks, rather than just projected onto women? Zen schools are like boot camp; where are the female roshis in Korea and Japan? The Tibetan word for woman means “lesser birth”; women serve tea to slake lamas’ thirst while they chant the rituals that women can sponsor but are rarely qualified to conduct. The Pure Land of Great Bliss has no women, the scriptures recount. Why not? For this, there is an answer: because it’s supposed to be pure and blissful!

If women must be excluded from purity and bliss, then the tradition betrays its own deepest truths of wisdom and compassion. No way around it: traditional Buddhism, like most religions, is dominated by men—in imagery, language, practices, hierarchical institutions, income, prestige, and perks. This is dangerous for women most visibly, for men more subtly. Does Buddhism’s male bias flavor its practices, encouraging, for example, the discounting of ordinary human bonds? With what results? Certainly, if men dominate all meanings, abuse and corruption are guaranteed.

“It were better for you, foolish man, that your male organ should enter the mouth of a terrible and poisonous snake than that it should enter a woman,” the Buddha said to a monk who slept with his ex-wife. The Buddha praised renunciate life as the best path to freedom, but he didn’t want to ordain women. Only after his softhearted attendant begged three times on women’s behalf did he relent. He required nuns to submit to Eight Special Rules explicitly subjugating them to monks (the nuns’ leader at the time protested) and later added at least 84 additional precepts for nuns on top of the monks’ 227, often stipulating worse penalties for similar infractions. Later, the Buddha sourly predicted that the nuns’ ordination would halve the life span of the dharma. (We’ve now surpassed his omniscience by several hundred years. Is Buddhism a dead science?)

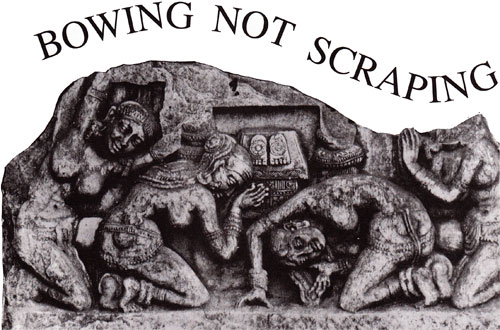

Under no circumstances may a nun criticize a monk nor admonish him. A monk bows to any monk ordained before him, but the First Special Rule of nuns says that a nun “even a of a hundred years’ standing” shall bow down before a monk ordained “even a day.” The strict seniority system, designed to eradicate caste in males, perpetuates subjugation—in pointed, nasty language—as soon as women appear.

Lots of people say that Buddha was using skillful means in restricting women’s privileges. Some even bend their minds, trying to discover meaning in the belief that it must continue thus; they remind me of Christians, not so very long ago, who found excellent justifications for the institution of slavery. More liberal thinkers say the Buddha had already rocked the boat enough by criticizing the upper classes: he was a reformer trying to get by in his Iron Age society. This is right, to some degree, since the Buddha often explained new restrictions by saying that laypeople would never gain faith in the dharma if they saw, for example, pregnant nuns. However, as the German biographer H. W. Schumann suggests, it may be simplest to conclude from the records that the historical Buddha didn’t respect women very much. This attitude can be considered secondary, if we feel entitled to form our own judgments about what’s valuable in Buddhist teaching and what isn’t. Just before his death the Buddha entrusted his monks to discard all minor rules, saying he knew they were able to discern the essence of dharma. Overcautious, the monks decided they couldn’t decide, and kept all the rules. In effect, they denied the Buddha’s last wish.

IF WE HAVE to have a bowing order, could it not be reversed on alternate days, with men recognizing the strengths of women, elders the potentialities of youth? Wouldn’t this equally express an important truth: that we all are trying to discover, and then expand upon, the seed of enlightenment all beings possess?

That’s what I thought in 1977 when, as a college graduation present to myself, I went to my first vipassana retreat in the redwoods above Mendocino, California. The teachers gave us one utterly simple method: turn awareness toward each moment, no matter what is happening. Each breath, each step, was its own fulfillment. Sometimes there were cloudy or joyous emotions, sometimes the beauty of young deer feeding in the meadow at dawn. I entered my life for the first time.

In the vipassana tradition of Thailand and Burma, I lived slowly and simply. For a time in 1988, I wore nuns’ robes at a monastery in Rangoon, Burma. Three years ago, I began practicing in the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition, learning the magnificence of the dharma’s full expression. I vowed to do 100,000 prostrations, a commitment whose magnitude is gradually making itself felt, in the form of sore knees. Buddhism reminds me to wake up, let go, be myself in each moment: this vivid and centerless clarity that belongs to no one, not even me, not even the Buddha. Practice is my reason to be a Buddhist, still.

I shaved my head and wore robes at one of the biggest monasteries in Rangoon, but technically I wasn’t a nun. The Buddha’s original nuns’ order, the bhikkhunis, vanished one thousand years ago everywhere except China, where an authentic Mahayana nuns’ transmission survives. A few monkly authorities support the spread of the Chinese lineage; women from many traditions now travel to Taiwan to receive full ordination and training. Yet the vast majority of devout women in Tibet, Burma, Thailand, and Sri Lanka still take fewer vows, and wear robes in a no-man’s-land outside the “real” transmission, where they are neither fish nor fowl, ordained nor ordinary. Many say they like the freedom of indeterminacy; that’s understandable, especially since it can be difficult to find monks and laypeople willing to provide the intensive support bhikkhunis need in order to keep their vows.

It’s not recorded why the bhikkhunis vanished, but their cumbersome relation with the male order must have been a factor. Bhikkhus had to support bhikkhunis’ retreats, ordination, and confessions. Meanwhile, both orders relied on the same lay community for food, shelter, and medicine. (Neither order works, nor handles money; a holy example is their offering to society. This system provides great feedback, since if monks and nuns don’t seem holy enough to ordinary folk, they must eventually disrobe, or starve.) What must have happened during famines? I’ve heard one monk claim it’s ten times as meritorious to donate to a male as to a female; perhaps ancient monks said or implied the same, even though the rules forbid angling for donations. A thousand years later, the male order’s resistance has not died out. One up-country Burmese master claimed he had found the only way to revive the bhikkhuni transmission. Hermaphrodites ordain as monks, then as nuns; but hermaphrodites can’t join the Buddha’s order in the first place. Ha, ha, it’s simply impossible! You see?

Still, when I was a Burmese thilashin, a “possessor of morality,” I loved being one of a tradition of determined women. The robes were beautiful; like the Buddha’s original nuns, I felt freed from unwelcome male advances, curiously freer to be fully womanly. Nonetheless, I used to muse sometimes that if the Burmese army, which was murdering demonstrators outside the monastery walls, should burst through the gates in a fever of blood lust, I’d get raped, nun or not. The robes’ protection wasn’t absolute; I was still a woman underneath.

The monks and monastery officials knew it, too. On the day the monsoon retreat began, my preceptor called me to his cottage. This was a privilege; by his delighted welcome, I could see he expected me to be pleased.

In his audience room fifty monks sat on the floor waiting for presents. Traditionally, at the beginning of the Rains, each monk is given new robes; my privilege was to kneel before each monk and, careful not to touch him, offer the packet with both hands. My knees hurt for days afterward; toward my preceptor I felt a weird combination of tenderness and rage. Need I say that no new robes were offered to nuns entering the same retreat?

The monastery’s secular treasurer kept calling on my fellow nun, a woman from California. He’d show her a photo of his nephew, a glowering young man who needed a U.S. green card. Would she marry him? If she’d been a monk, the treasurer wouldn’t have dared. Burmese respect their monks, even half-baked Western ones.

I began to wonder whether I wanted to spend my life as a representative of inequity. I asked a junior abbot how a nun disrobed: if I went to the States and was unhappy, must I fly back to Burma and find my preceptor?

This big, handsome monk had charge of all Burmese women meditators, interviewing four hundred each day. “You’re not a nun. Anyone can shave their head, wear pink shirts, and not eat dinner, even a man. No monk is needed to disrobe you.”

Shortly afterward, the translator monk made a nasty remark about one of the sponsors. “She’s nothing but a woman,” he sneered. Since she had no other apparent faults, and had helped us generously, we Western ladies went to the abbot.

“Why do monks disparage women?” we asked. Needless to say, the disparaging monk was translating; he showed no discomfort as he passed our words to the abbot.

The abbot replied that this did not occur, since monks perceive no men and women, only impersonal body elements and mind. Had we not experienced this in meditation, too? Oh, yes, we said. He went on in praise: more females lived in the divine realms, since women are more ethical than men. Women got enlightened more easily, because we suffer more, thus easily renouncing the world. We’re better meditators, docile in following instructions.

“Then why are there no women teachers, if women are so enlightened?”

The abbot paused. “Women are lazy,” he said, “and hate responsibility. Wives sit around at home until the husband hands over his wages, then they go shopping. In the same way, nuns and female meditators let monks support them spiritually. When Burmese peasants carry a heavy load of rice, they divide it into two sacks and tie one to each end of a long, strong bamboo. Two people shoulder the load, but if the person to the rear creeps forward, the person in front bears most of the weight. That’s how women do. ” He looked so proud of this analogy that we hardly dared go on. But the translator was smirking, and I felt outraged. “Housewives pound rice and carry water, and never get paid or respected. Women do seventy percent of the world’s labor, eat twenty percent of the food, and get ten percent of the pay.” My numbers were inexact, but good enough for Rangoon. The monk-translator didn’t bother to pass this on, but answered me himself. “Who will pay these women? Men?”

We women could only bow and leave.

My Burmese teacher was right: I have not yet taken full responsibility for carrying the truth. For one thing, there’s evidence that I’m not fully connected with wise, loving, authentic Buddha-mind. Why else do I keep swallowing and then spitting out Buddhist-isms—the mere husks of truth?

I’m not saying it’s easy. In traditional contexts, questions can bounce back as accusations. Sermons, admonitions, and gossip tell us what to think of doubters: they’re full of greed, anger, ignorance, intent to harm, pride, and bad manners—Dharma Enemies bound for Vajra Hell. Most Asian teachers aren’t interested in learning “worldly things” from us, the “red-faced barbarians” who come to them for wisdom. But is equality among beings “worldly”? The Greeks were inventing democracy around the same time as the Buddha sat down to rend the veils of illusion. Perhaps it’s time now for the world’s two greatest ideas fully to recognize their commonality.

THREE YEARS AGO, I first heard Tibetan Vajrayana teachings on the nature of mind. It was like falling in love with an old friend. I liked the tradition’s joie de vivre, how lamas moved and laughed, so much more flexibly than the tight-wrapped Theravadins. (Sometimes too flexibly, as when I learned some lamas are multiple seducers, a form of misbehavior quite rare in my previous tradition.) Finally, I was glad to hear that there are many female Buddhas, plus a tantric vow not to look down on women. But to whom is that vow addressed?

I vowed to do a Ngondro, or preliminary practice, which begins with 100,000 prostrations and refuge prayers. This combination is supposed to reunite me with the essence of my enlightened mind, purify all obscurations, and prepare me for Vajrayana practice. I certainly hope so! After 19,000 prostrations, the magnitude of the commitment has begun to dawn. My deltoids are burgeoning. My knees click. Any sane person would have doubts; mine take the form of wondering whether Ngondro is really good for me.

Here I am, a Western feminist, abasing myself physically in front of an odd Tibetan painting—of a man. Of all possible symbols of truth, is this the one for me? Yet in the refuge prayer that runs, half-garbled, through my mind, I also vow “to reach the level of the guru.” Who is that guru? What’s his level? Examining the tanka painting, I see the eighth-century Indian spiritual patriarch Padmasambhava on his lotus throne, that flying saucer on which he erupts from his idealized Himalayan background trailing sacred white scarves. Will I ever reach his level on all three tantric senses—outwardly, inwardly, secretly? Or must I be content with secretly and inwardly, while visible thrones are reserved for men? For an answer, at the bottom of the tanka sit Padmasambhava’s two tiny consorts (he had five). The women arch gracefully toward the master, parabolic mirrors reflecting his glory. Meanwhile, Padmasambhava stares, frowning, straight out of the painting.

Like many other Western women practitioners, I mentally repaint the tanka to console myself. I add Tara, compassionate remover of obstacles; Kuan Yin, the all-encompassing; Sojourner Truth, liberator of slaves; and the Lionheaded Dakini, a wrathfully dancing female deity, to my Ngondro refuge tree. When I make my prostration’s final slide toward Padmasambhava’s outstretched boot, I often imagine Yeshe Sogyal touching my head in blessing. I like Yeshe, whose name means wisdom. After her enlightenment became equal (almost) to Padmasambhava’s, she went off on her own, raised a sixteen-year-old Nepali warrior from the dead, and took him to a cave for tantric practices. . . . Maybe I’d like to be some combination of Yeshe Sogyal, Susan Sontag, and Sojourner Truth.

Did the boy act like a lama’s wife, fetching tea while Yeshe rang her bell and muttered over her pechas, those long, skinny, unbound Tibetan prayer books? I wish I could think their relationship was equal, but then I’m the heiress of an expanded Greek democratic ideal, while Yeshe Sogyal was not. When she acted as secretary, recording events at famous eighth-century tantric gatherings, she’d list the princes, lamas, and yogis present by name and lengthy title. At the end, she named herself most simply: “And I, the woman, Yeshe Sogyal.”

Woman would be title enough for me too, all other things being equal—which they’re not. Raw experience bears no label: I learned from outside I’m a woman. Why do people fixate so strongly on the difference? If the Martians landed, they’d confuse all two-eyed beings with legs: cats, dogs, Chinese, butterflies, and dreamers.

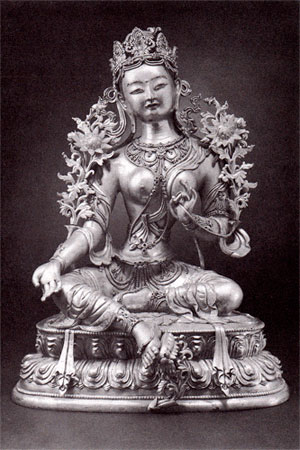

Green Tara, seventeenth century, Tibeto-Chinese,

gilt brass with inset gems and pigments

I hope one day that all of our perceptions will shift to a more open, universal field. So far, alas, men still seem to be hanging on to a position at the center of the centerless universe. Examining other tankas, I note that female Buddhas are rarely the principal figure. Rather, they’re mostly faceless, sitting with their back to the viewer, necks painfully twisted sideways. They’re consorts, emanations of the male. His qualities, his light, his empty or material aspect. I appreciate men’s efforts to connect with socalled feminine qualities, but this does seem a man’s view of women. Texts say all women should be seen as dakinis, female emanations of enlightenment; but in practice, this word often seems to equate with “sexual object.”

Yes, there’s Tara, and Vajrayogini; dakinis, khandros, and one or two female rinpoches and tulkus; so few they prove the rule. If wisdom’s really nondual, why isn’t the proportion fifty-fifty? Why are there no enlightened women on altars, on thrones, in books, pictures, or lineage prayers? “There’s Sogyal Rinpoche’s aunt—Jamyang Khyentse Chokyi Lodro’s wife,” one friend said. But what’s her own name, I wonder; does anyone know it? Why hardly any women tulkus (enlightened incarnations)? “Bodhisattvas don’t really make decisions,” a scholar said smugly. “They just get reborn where there’s a need, according to circumstances. Women can’t accomplish anything, so they don’t come back as women.”

It would be a fine accomplishment, I think, to help all beings to perceive liberation in female form.

Right now, my male partner is closeted with our lama getting a special, secret teaching. I’m jealous, frankly. If I made 400,000 prostrations, learned Tibetan, and did all the other things he’d done, would I qualify for same? And if the tradition is so macho that I wouldn’t, why should I bother? After her million and a half prostrations, I am sure the lama’s wife has not received this transmission—but also sure that she doesn’t feel too deprived. I’m terrified to ask Rinpoche about this. He’s blissfully undogmatic, but he’s still an elderly Tibetan. What if he finds something to dislike in my intentions, actual or perceived? I don’t know if I can bear to be disappointed. I wouldn’t want to shame his wife, who’s always in his room, sitting on the floor at his feet.

Is this a cop-out? I gather courage and go in to ask my question. I prostrate to Rinpoche on his carpeted bed. The old lama is amused, even slightly interested in discussing men and women. “Is your mind shaped like this?” and he loops his fingers, forming a vagina. “Is my mind shaped like this?” He holds up his forefinger, a phallus.

“No!” We laugh together. His wife, sitting on the floor behind us, below us, laughs too.

I KNOW reality’s transparent; nonetheless, it seems to have its effect on nearly everyone. All over this floating world, women fear to walk alone at night. According to JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, violence by male intimates is the leading cause of death for women in the U.S. between the ages of fifteen and fifty, surpassing auto accidents and disease. At least twenty-five per cent of women are sexually abused in childhood; adults all endure seeing our bodies splayed across billboards, used to sell everything from tractors to iced tea—to celibacy, as in the painting at Wat Suan Mokkh. When the massive patriarchal system that tacitly encourages such crimes grinds on unquestioned—even is enshrined as holy—how can women not feel revulsion?

It’s not my job to get my sixty-year-old lama and his wife to sit in chairs of equal height. My Asian teachers are trying to help me by passing on what’s valuable; some younger ones ask questions about sex issues and eco-friendly housing. This year, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has promised to convene a monks’ council, and ask them to change the rules subordinating nuns. He says he can’t be certain of his influence, but he will do his best.

Yes, the situation’s changing. It’s been difficult even for Western males to cross racial barriers and be empowered by Asian masters; but some have, and they tend to be more flexible and democratic than Asian teachers. Fewer women receive such recognition, but there are some. When Burmese villagers threw rocks at the Western nun Shinma Beyri, the late Yen. Taungpulu Sayadaw accompanied her on her alms round, an ascetic practice usually denied to mere thilashinnuns (they’re supposed to eat the monks’ leftovers). The villagers quit throwing rocks; eventually Shinma Beyri was able to gather alms independently. Returning after many years in the East, Beyri now lives in Colorado, where she works with disabled and dying people, a perfect field for her deep experience of practices that break the mind free from false images of the body. Another Asian teacher, the late Yen. Kalu Rinpoche, offered Western men the title of “Lama” after they did a three-year retreat. He offered women the lesser title “Ani,” nun, for the same qualification; but somehow Lama Kalu’s women disciples are slowly becoming “lamas” too. Changing a tradition isn’t easy: even the Venerable Kalu was criticized for his liberal gestures.

But if we look a little more closely at the institutions, there’s been little in the way of genuine change. Twenty-five hundred years ago, the Buddha’s stepmother, Mahapajapati Gotami, who breastfed him after his mother died, became the head of the nuns’ order. She said it would be good if men and women in his order could revere each other on a basis of equality. The Buddha’s recorded reply was that if false teachers do not allow women equal status then how much less could he—the true teacher—allow them equal status. In the case of women, the Buddha was wrong—and we have to have the courage to say so.