The road to Ram Dass’s home on the north shore of Maui winds from the Hana Highway toward the roiling Pacific. The sage green split-level sits on a lushly landscaped rise overlooking the ocean; waves crash against the rugged shore below, and trade winds whip the palms and Norfolk pines.

This is the Hawaii of surfers’ dreams and National Geographic photo spreads, the Hawaii of poetry and the imagination. It’s a rare day when a tropical afternoon shower does not produce a spectacular rainbow, one end of which often pierces the ocean like a blade.

I am here for a five-day private retreat with Ram Dass. My friend Liz and I will stay in the guesthouse on his estate and spend private time with him each day. I have no idea what to expect.

In 2004, I came to Hawaii for Ram Dass’s first Maui retreat, a small gathering of about 25 people. Each afternoon we’d trek from the retreat center to Ram Dass’s rented house, and in the intimacy of his living room he would give a dharma talk and answer questions. After that retreat, he fell gravely ill with a septic urinary tract infection. When he recovered after several weeks in the hospital, he was finished with traveling: Maui would be his new home.

During that first retreat, Ram Dass spoke often about death and dying; as he got older the subject appeared to intrigue him even more. Seven years earlier, a massive stroke had nearly killed him and had left this incredibly glib man with expressive aphasia, extreme difficulty in producing language, and the right side of his body paralyzed.

“Dying is like a Bingo game,” he said at one point during that 2004 retreat, searching for words in “the bombed-out closet” of his mind while sucking on Tootsie Pops. “When you die and are finished with the Sturm und Drang of the incarnation, you realize that the incarnation was like the five you needed to get Bingo.” The stroke may have slowed him down, but it had not diminished his wicked sense of humor.

Today Ram Dass still grapples for words, but his vocabulary is richer and he becomes more fluent as he converses. He hates it when you try to find a word or finish a sentence for him unless he specifically asks for help. Ram Dass says the stroke brought him closer to his center and made it easier to relate to the suffering of others.

“There is grace in suffering. Suffering is part of the training program for wisdom,” he says.

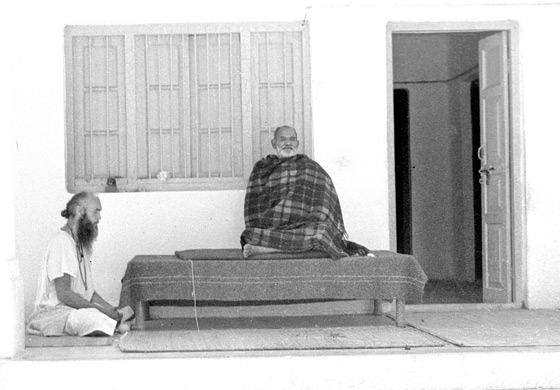

Over 50 years of spiritual practice, utter faith in his guru—Neem Karoli Baba—and a devoted network of friends have allowed him to spin the stroke into a positive experience. He sees himself as a beacon for the aging baby boomer population, one step ahead on the journey toward physical decline and eventual death.

Related: Tricycle Talks: Buddhism and Psychedelics

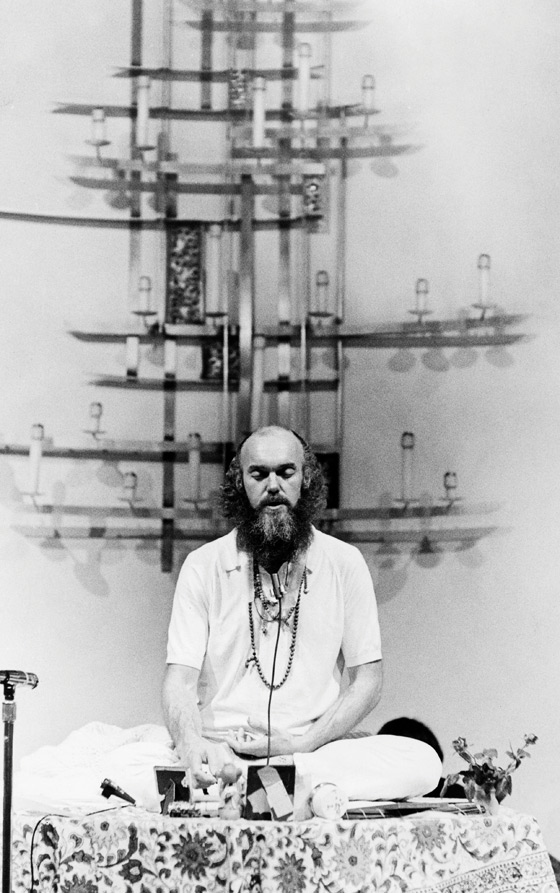

Born into a Boston Brahmin family in 1931 as Richard Alpert, he was a freewheeling, sports car–driving psychology professor at Harvard when his colleague Timothy Leary turned him on to psilocybin in 1961. That experience totally changed his life.

“When I took my first trip, I knew I was home,” he tells me.

Although Dr. Alpert was sanctioned to conduct psychedelic experiments with graduate students, when he gave LSD to an undergraduate in 1963, he was fired. Later, he headed to India, where he met his guru, whom he calls Maharaj-ji. It was Maharaj-ji who gave him the name Ram Dass, which means “servant of God.” When Ram Dass’s beloved teacher told him to go back to the United States and “write his book,” he had no idea what book Maharaj-ji was referring to. But once back in the States, he wrote Be Here Now, which has been in print since its publication in 1971 and has sold over 2 million copies. Since then he has written 11 other books.

When Ram Dass arrived home from India, barefoot in flowing white robes, his father, George Alpert, president of the New Haven Railroad and one of the founders of Brandeis University, ushered him into the car, hoping no one would see him. He mocked his son, calling him Rum Dumb or Rammed Ass. Yet in Fierce Grace, a 2001 documentary about Ram Dass, George Alpert seemed delighted to welcome the hundreds of hippies who swooped down on his New Hampshire farm to be near his son.

“When the cameras were rolling,” Ram Dass recalls, “he was a different person. He was acting.”

There was a poignant reconciliation between the two when his father was dying, but as Maharaj-ji counseled, Ram Dass turned down his substantial inheritance.

I attended that first retreat right after my own father’s death. I wanted to spend time with the man whose CDs on death and dying had helped me transform that experience into a collage of precious and intimate moments. By hearing Ram Dass’s take on his own father’s death and the bedside vigil he kept as his stepmother died, I was able to be present during my father’s final months and embrace the truth in the dying experience.

Now, eight years later, I am back. Ram Dass will turn 82 in a couple of months—if I don’t hang out with him now, when?

There is nothing five-star about the guesthouse, a funky two-room studio with a shower in the kitchen. Pictures of Maharaj-ji adorn the puja altars in each room. Tomes by Ram Dass and other spiritual teachers—Stephen Levine, Deepak Chopra, and Thich Nhat Hanh among them—fill the bookcase. There’s a boom box and CDs by Krishna Das and Jai Uttal. We are free to use the pool and Jacuzzi, both of which have breathtaking views.

Ram Dass is wheeled into the guesthouse the next morning by his young Sufi assistant, Muib. Barefoot, dressed in shorts and a Hari Om T-shirt, Ram Dass fiddles with the baseball cap in his lap with his left hand. His right hand, its fingers slightly bent in on themselves, has been rendered useless by his stroke. He is thinner than the last time I saw him, though still a tall and elegant man. A rotator cuff injury makes it almost impossible for him to raise himself out of his wheelchair without assistance; at one point, he describes himself as having no arms because of the injury.

Naturally, we speak about death; the subject fascinates me, too. Twenty years ago, I wrote a book about the impact of AIDS on the artistic community and spent two years interviewing dozens of artists living with—and dying of—the disease. And over the past few years, I have volunteered to sit with the sick and dying, an experience I shared with my father and recently, my mother.

“The medical establishment does everything it can to keep someone alive,” Ram Dass says. “This culture says, ‘Don’t go, don’t go,’ and priests or rabbis say, ‘It’s okay to go.’ You need to stay in the middle. Don’t let your model of death interfere.”

Related: A Good Death

Years ago, Ram Dass and Stephen Levine started a dying hotline. People on their deathbeds could call in and be supported through the process—“pillow talk,” Ram Dass calls it.

“All you can do is love,” he adds. “Be a loving rock they can push against. You shift when they shift.”

I ask Ram Dass how I can reconcile the part of me that can sit with an open heart with a dying stranger and the part that often feels, to quote Jean-Paul Sartre, that “hell is other people.” But before he can respond, the answer is clear to me.

“I guess I don’t have to make much of a commitment to someone who is dying,” I blurt out.

Ram Dass bursts into peals of laughter. “Boy, oh boy, you’re honest!” he exclaims, slapping his knee with his good hand. He tells me that when people rub me the wrong way, I must focus on their souls rather than their egos.

“Their karma is their dharma,” he says. (He often speaks in pithy little nuggets of wisdom.) “We go from here, ego,” he says, tapping his head, “to here.” He pats his heart. “What I call the soul, the spiritual heart. That’s the path. Then you can view your life with a sense of detachment.” He closes his eyes and places his hand on his heart. “I am loving awareness,” he whispers.

As he repeats “I am loving awareness” and we begin to meditate, I experience my ego dissolving, the boundary between us becoming nebulous. A feeling of oneness permeates the room, and my heart is flooded with love. I have experienced this egoless, deep-hearted love before, once a few years ago with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in a small group at a Jewish temple in California. It is the same feeling we chased after, again and again, with psychedelics and other drugs in the sixties and seventies.

A couple of days later, Ram Dass comments on the phenomenon.

“This is new,” he says. With his left hand, he lightly stirs the air in front of his face. “The aura thing.”

He thinks this state would be even more accessible if his ego didn’t admonish him when it happens: “Who does he think he is to embody Maharaj-ji?” When he can let go of the negative voices, the dissolve we experienced—“the aura thing,” as he calls it—is more frequent.

He touches his forehead with his long, elegant fingers.

“I really felt Maharaj-ji in the room during the meditation,” he tells me.

I definitely felt something. And now, a day later, it is as though the hard edges of my personality, which I had just the day before said I wanted to be rid of, have disappeared. I feel softer, more vulnerable.

“How much do I have to pay for the private retreat with LSD?” I joke. Ram Dass laughs heartily. He appreciates my sense of humor.

The first object I notice when I enter Ram Dass’s house the next day is a rectangle of dirty carpeting hanging on the wall in the foyer. Reverentially framed with a Tibetan prayer scarf, akata, this piece is an inside joke between Ram Dass and Mickey Lemle, the director of Fierce Grace. In an Indian restaurant years ago, Ram Dass was going on expansively about how he loved everything, even the soiled carpeting underfoot. Mickey jokingly noted that if that were the case, it would no longer mean much when Ram Dass told Mickey that he loved him—not if he loved the restaurant’s disgusting carpeting, too. So Mickey gifted Ram Dass this piece of cheap, beige carpeting with a shocking black smear in the center. Ram Dass displays it with no irony, as prominently as a photograph of a Maui rainbow and a portrait of Neem Karoli Baba.

On the majestic puja altar in the living room, there are photographs of Anandamayi Ma, Shivabalayogi, Lama Tsultrim, and Barack Obama, among others. A photo of John Boehner, like the one of George W. Bush that was on the altar during Bush’s presidency, reminds Ram Dass to love the soul in whatever incarnation it finds itself.

“A satsang, all yearning for God,” Ram Dass says about this assembly of spiritual teachers (Boehner included).

In his kitchen, Liz and I unload groceries. Tonight we’re making dinner: two kinds of pasta with half a dozen varieties of local mushrooms. A candle burns in front of a picture of Maharaj-ji on the big center island. Tiles on a Scrabble caddy spell out Be Love Now, the title of one of Ram Dass’s books.

I check the six-burner stove and the pots and pans hanging above it. Though the clock on the wall says it’s half past “now”—there are no numbers, just the word “now” at the quarter hour marks—everything runs on a set schedule. Dinner is at 6:30 p.m., give or take 15 minutes. The Daily Show and The Colbert Report are taped and watched afterward in a little alcove that holds the big-screen TV.

Dassi Ma, Ram Dass’s confidante and personal assistant, keeps things flowing as precisely as a majordomo but as lighthandedly as a hippie, thanks to an imperturbable personality and the organizational skills acquired as a corporate HR executive back when she was still Kathleen Murphy.

“She protects me,” Ram Dass says. If things get too hectic, he retires to his apartment on the upper floor of the house, where he works at his computer or reads, lately books on near-death experiences like Nanci Danison’s Backwards.

It can and does get hectic. This week Bokara “Bo” Legendre, an old friend, is visiting, as is Lama Surya Das. I see them meditating on the long sectional couch in Ram Dass’s living room and later heading to the beach in a rented convertible with the top down. Joan Halifax visited recently; Wes Nisker, Jack Kornfield, and Trudy Goodman come a couple of times a year. Mirabai Bush, treasurer of Ram Dass’s Love Serve Remember foundation, is due any day, as is Zach Leary, Tim’s stepson.

Tonight, though, the house is quiet. Although he generally eats spartan vegetarian fare—the fridge brims with organic produce, a bag of raw cashews, sparkling water—Ram Dass loves the occasional epicurean indulgence. He gobbles the perfect mango I offer one morning before our meditation. He savors Liz’s Hanuman-shaped organic chocolates. And tonight he digs into the pasta, refilling his plate, as Bo regales us with stories of her socialite mother who spent the roaring twenties big-game hunting in Africa.

Over chocolate and tea, Ram Dass describes his first trip with Leary, which ended with him shoveling his parents’ driveway in a snowstorm at five o’clock in the morning, to their considerable dismay. He has tripped once since his stroke, with his doctor, but now he doesn’t even smoke pot.

“I used to smoke for them,” he explains, for his audiences, whom he assumed were all high. Smoking before he went on stage put him on their wavelength, or so he thought when he saw their heads nodding in unison from the stage. But now he’s not high and they still nod their heads.

Today the back of Ram Dass’s white Honda Crossfit is packed with life jackets, floats, and towels, and we are heading to Kamaole Beach in Kihei for the weekly ocean swim. There we are joined by a motley group of friends and fans representing every age from teen to octogenarian.

When I hesitate about swimming in the chilly Pacific, Ram Dass nudges me until I dive in. I know I will regret it if I ignore his urging. A dozen of us glide to the limit of the swimming area; Ram Dass, in a life vest, propels himself on his side with his good arm and leg. He grabs hold of the floating marker and, eyes closed, blissfully repeats “Oh buoy, oh buoy,” punning on one of his favorite expressions. Lili, the septuagenarian self-appointed “minister of fun,” has us join hands and chant: “If it’s not fun, don’t do it. If you must do it, make it fun!” Tom, a middle-aged surfer/photographer, flings delicate jade flowers and hibiscus blooms that bob, as we do, with the waves.

Back on the beach, two young musicians from Portland sing for Ram Dass, kneeling at his feet. A man wheels his skeletal friend over in a beach buggy. Ram Dass takes the dying man’s hand and sits with him, eyes closed, not saying much. Tears in their eyes, the two men are visibly moved.

Afterward we head to a nearby restaurant, Pita Paradise. Ram Dass orders hebi, a local fish, and a Diet Snapple. I sit opposite him. When Liz oohs and ahhs over the potatoes on my vegetarian platter, Ram Dass orders me playfully, but sternly, to “give her some.”

I offer her my plate, of course, and we all laugh. For a second, it felt like a father admonishing his daughter to share with her sibling.

Ram Dass is a father. Four years ago, he found out he had a son, Peter Reichard, an investment banker who lives in North Carolina. When Peter’s younger brother first contacted Ram Dass, he thought he was being hustled. But a DNA test confirmed that Peter was the result of a fling over half a century ago, when Ram Dass was a graduate student at Stanford.

“Can you believe I found out at 79 that I had a 53-year-old son?” he asks incredulously.

The two men look remarkably similar, tall and lanky with the same smile and distinctive hairline.

Ram Dass, who has had relationships with both men and women, never wanted children, had never placed much value on family. But now that Peter is in his life, the man who famously said “If you think you’re enlightened, go spend a week with your family” seems to be rethinking the connection. He lights up when he speaks of his son visiting him in Maui with his wife and daughter. One Sunday in the guesthouse, he gets fidgety when Muib is a couple of minutes late to wheel him back. It is nearly one o’clock; he does not want to be late for his weekly Skype date with his son.

The last morning of the retreat, Ram Dass knocks on the guesthouse door. He has come bearing gifts: pictures of Maharaj-ji and malas knotted with threads from Maharaj-ji’s blanket.

In the late afternoon, the musicians from the beach come to the house for an improvised kirtan, just a handful of us sitting cross-legged on the sofa. Nobody seems to remember the words to the Hanuman Chalisa—definitely not the musicians, who have never played kirtan before—but when they segue into the familiar call-and-response chants, we sing our hearts out.

I pick up a drum and find the beat. Ram Dass beckons me to hand him the finger cymbals.

“You’ve got rhythm,” Ram Dass tells me.

I’m sad to be leaving, I say. I am, in my heart, and want to stay there.

He takes my hand.

“You will be bathed in loving light whenever you want it,” he assures me. “That’s what grace is.”

Polishing The Mirror

For over 40 years, Ram Dass has been exploring—and writing about—a soul-centered life path, his journey from living in his head to living in his heart. Since his first book was published in 1971 (Be Here Now, which has sold over 2 million copies), he has described the various methods and experiences that have helped him navigate his own life’s voyage: psychedelics, meditation, bhakti yoga, karma yoga, guru kripa, prayer, service, and working with the dying, sick, and aging.

His latest book is Polishing the Mirror: How to Live From Your Spiritual Heart (Sounds True, 2013), written with his friend and collaborator Rameshwar Das. The book’s title is inspired by the first line of the Hindu devotional hymn Hanuman Chalisa: “I cleanse the mirror of my heart with the pollen dust of holy Guru’s lotus feet.”

“This internal reflection,” Ram Dass writes, “can also be seen as a process of witnessing . . . our own actions, thoughts, and emotions with an attitude of tolerance and love.”

Ram Dass has been polishing the mirror of his heart for decades. Now 82 years old, he has the process down pat. “As you become more aware of what gets you to God and what doesn’t,” he writes, “you will naturally let go of what doesn’t.”

For those negotiating this process, Polishing the Mirror offers an eclectic tool kit. Kirtan chants and meditation suggestions are mixed with classic Ram Dass stories, tales from the Hindu epic Ramayana, and poems by Rilke and Rumi (and Hallmark!). His take on subjects such as karma and relationships blends with his observations on aging, changing, and dying.

His message, as clear as it has always been and delivered with his inimitable humor, does not deviate much from the original words of wisdom he received from his guru, Neem Karoli Baba, many years ago: Love everyone and tell the truth.

The fact that this book does not get into the deeply personal exploration of his own final chapter—the book that would be the natural follow-up to Still Here, which ends with a recounting of his devastating 1997 stroke—leads us to think that Ram Dass has at least one more book in him.

Or not. As he notes, “your romantic attachment to your own story line and how it comes out fades.”